John Guare's brittle satire, first produced in New York in 1990, was propelled by two phenomena. The first was a certain David Hampton, a con man who persuaded a suite of gullible Manhattan socialites that he was Sidney Poitier's son (and who, when Guare's play became a hit, pestered the playwright for a cut of the profits). The second was the theory, developed by various writers and social psychologists and vastly popularised by Guare, that "everybody on this planet is separated by only six other people". Since then, though, the planet has changed beyond recognition. How does Six Degrees of Separation, in this suave, fast-moving revival, stack up two decades down the line?

This is how it starts: in a swanky Upper East Side apartment, a middle-aged married couple, Ouisa and Flan Kittredge, are walking on eggshells. Art dealers, they must inveigle a visiting South African into bankrolling the purchase of a Cézanne that they will own for an intoxicating few days before flogging it off at a fat profit. Suddenly a young man, Paul, arrives at their door, desperate and bleeding: a college friend of their children's (so he says), he has just been mugged and didn't know whom else to turn to.

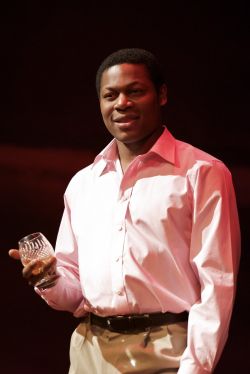

It looks like the evening is headed for disaster but Paul, as it turns out, saves the occasion, rustling up a gourmet scratch supper from the ancient leftovers lurking in the fridge, discoursing passionately on J D Salinger's The Catcher in the Rye, dazzling his hosts with the prospect of bit parts in his father's forthcoming movie musical and eventually wheedling those two million bucks out of the South African's pocketbook. (He is played by Obi Abili, pictured right: credit, Manuel Harlan). Delighted, the Kittredges, with a thrill of radical chic, insist their new friend stay the night: such a nice young man, and black too, how exotic! But then Paul just has to go and spoil it all by bringing (full frontal nudity alert here) a rent boy into his bed.

It looks like the evening is headed for disaster but Paul, as it turns out, saves the occasion, rustling up a gourmet scratch supper from the ancient leftovers lurking in the fridge, discoursing passionately on J D Salinger's The Catcher in the Rye, dazzling his hosts with the prospect of bit parts in his father's forthcoming movie musical and eventually wheedling those two million bucks out of the South African's pocketbook. (He is played by Obi Abili, pictured right: credit, Manuel Harlan). Delighted, the Kittredges, with a thrill of radical chic, insist their new friend stay the night: such a nice young man, and black too, how exotic! But then Paul just has to go and spoil it all by bringing (full frontal nudity alert here) a rent boy into his bed.

The scam is very far from being the play's main point, though. Instead, it's the springboard for a densely packed rumination on art as commerce, celebrity culture, the unbridgeable generation gap, racial politics, bourgeois delusion, the very American Gatsby-like flair for self-reinvention and much more besides, all played out in a curved womb-like arena of pulsating crimson, like a CinemaScope Rothko.

In the shifting-sand dramatic structure, characters step forward to confide in the audience, remembering dreams or events that are then re-enacted in short, sharp flashbacks. What seems at first, in the long introductory scene, to be shaping up as a four-character chamber piece spirals out into a chaotic tragi-comic farce with 18 speaking parts.

The director, David Grindley, has decided against updating the setting, which would in any case have been tricky. It's not just the references to apartheid and Cats: with its backdrop of a New York ravaged by Aids, drugs and crime, a crazily inflated art market, and an era whose style was set by Gordon "Greed is Good" Gekko and Tom Wolfe's Masters of the Universe, Six Degrees of Separation is very much of its time (though the couple's precarious finances, their house-of-cards lifestyle, has a recognisably modern ring to it as well).

The Kittredges schlep along to a downtown bookstore to buy Poitier's autobiography, wherein they read that he has only daughters; no son. As Guare himself has pointed out, nowadays a couple of quick Google or Facebook clicks would have unmasked the imposture. And anyway, given today's obsessive-compulsive social networking, isn't the small-world theory itself a bit old hat?

In fact, the play seems to me about not connections but just what it says on the tin: separation. For all their superficial bonds, Ouisa, the brilliant social butterfly, discovers the chasm between herself and her peers, her children and her mate: "We're a terrible match," she says at the end in the tones of someone facing an awful revelation. Conjugal relations, you gather, are not much to write home about; on the other hand, there's a definite sexual chemistry with the stranger, Paul, near the start which, by the end, has turned into a complicated sort of love.

Vulnerable, blinkered yet bright, Ouisa is the play's focus. Stockard Channing took full possession of her in both the original New York and the 1992 London productions: I saw her at the Lincoln Center, just a few blocks across Central Park from where her character would have lived, charming an audience of similar moneyed and cultured Upper Manhattanites in that odd, slightly cracked voice of hers. Channing was Oscar-nominated for her performance in Fred Schepisi's much more cluttered and naturalistic 1993 film version, though slightly overshadowed by a star-making turn from the then little-known Will Smith as Paul: watch Channing here as Ouisa (spoiler alert: the scene comes right from the end of the film. It has French subtitles too).

For all the spectacular range of her theatre roles (recently in the stage adaptation of Pedro Almodóvar's All About My Mother), Lesley Manville, the Old Vic's Ouisa, is associated with the very different world of Mike Leigh, especially the blue-collar love story All or Nothing (pictured left) in which she starred; the two have just completed a new film, their sixth, together. She gives a great account of Ouisa's awakening and that shattering last speech, but her version is slightly more difficult to warm to; in angular grey and black tailored frocks with vintage big shoulder pads, she looks petite and a little fragile. The film's upbeat ending implied that Ouisa breaks out of the doll's penthouse, but that certainly isn't indicated here.

For all the spectacular range of her theatre roles (recently in the stage adaptation of Pedro Almodóvar's All About My Mother), Lesley Manville, the Old Vic's Ouisa, is associated with the very different world of Mike Leigh, especially the blue-collar love story All or Nothing (pictured left) in which she starred; the two have just completed a new film, their sixth, together. She gives a great account of Ouisa's awakening and that shattering last speech, but her version is slightly more difficult to warm to; in angular grey and black tailored frocks with vintage big shoulder pads, she looks petite and a little fragile. The film's upbeat ending implied that Ouisa breaks out of the doll's penthouse, but that certainly isn't indicated here.

The other roles are much sketchier - this is a play of self-consciously clever big ideas, not complex characterisations. Anthony Head is adequate as Flan, the art-lover who has sold his soul to Mammon, and some of the younger actors (Zoe Boyle especially as their defiant daughter) leave their mark. Above all, Abili infuses Paul, the street kid so desperate to be accepted into polite society that he's prepared to stab himself to gain entrée, with tremendous charisma, exuberance and eventually pathos. In 2010, he could and should be the story's main character but he remains a disposable dramatic device to smooth the white liberal's guilt-ridden voyage of discovery. That, probably, is the play's most dated aspect of all.

Add comment