I reviewed excerpts of Will Gregory's new opera, Piccard in Space, last year. His funky, plushly Moog-ed, concerto-like suite struck me as rather tasty. I even said that I couldn't wait for last night's fully worked-out operatic world premiere at the Queen Elizabeth Hall. How wrong I was.

What a slap in the face for the human predicament that an opera which, for all its faultlines, should carve "love and courage will set you free" on every heart meets with barely a moment of truth in Jürgen Flimm's production. It's the second Covent Garden revival in a month to give no sense of people or place, and like the McVicar Aida, it should have been put quietly to sleep after its first run. "But Nina Stemme will be wonderful," they all said. Don't bank on it; just be thankful that the soprano's Leonore and, perhaps more impressively, Endrik Wottrich as the imprisoned husband she saves are up to the vocal challenges.

What a slap in the face for the human predicament that an opera which, for all its faultlines, should carve "love and courage will set you free" on every heart meets with barely a moment of truth in Jürgen Flimm's production. It's the second Covent Garden revival in a month to give no sense of people or place, and like the McVicar Aida, it should have been put quietly to sleep after its first run. "But Nina Stemme will be wonderful," they all said. Don't bank on it; just be thankful that the soprano's Leonore and, perhaps more impressively, Endrik Wottrich as the imprisoned husband she saves are up to the vocal challenges.

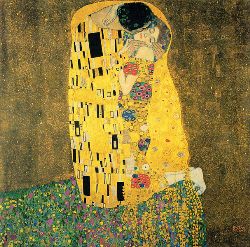

A glittering, gaudy surface and an epic, sometimes disturbing underbelly are what many of Klimt’s canvases and Richard Strauss’s autobiographical bourgeois comedy of marital misunderstanding have in common. It was the main idea of Wolfgang Quetes’s Scottish Opera extravaganza to bring those mythic resonances in harmony with the realist conversation-piece aspect of the opera. But you don’t do Intermezzo without a capricious heroine of huge charisma like Glyndebourne charmers Elisabeth Söderström and Felicity Lott. Any British opera-goers heard of Anita Bader? You will now.

Bader makes very much her own the role of Christine Storch, a feisty stage personification of Pauline Strauss, the moody dame the composer has his stage alter ego undiplomatically describe as a prickly hedgehog with a lovely inside. While Söderström and Lott at Glyndebourne had immortal glamour, there’s more than a hint of Bavarian hausfrau about Munich-trained Bader’s sharp-featured funny face. But she’s immensely graceful with her arms and hands, and the voice is of the warmer, less cutting Straussian variety, not always pitch perfect but never strident (hard to believe she’s sung Turandot, but then the top notes do ring out). And the physical warmth and ease between her Pauline and long-suffering, if just a tad complacent, Robert Storch - the rugged, broad-phrasing young baritone Roland Wood - in their opening spats ease the audience into realistic, complex comedy from the start.

It darkens, of course. The premise is an incident which befell the Strausses in 1902, 22 years before the opera was composed, when Pauline opened a letter addressed from a Berlin good-time girl to her famous husband in familiar terms, only to discover that the silly thing had mixed him up with a mere Kapellmeister, Josef Stransky (Stroh in the opera). To make the work more symmetrical, Strauss gives Christine a fraught flirtation with the opportunistic young Baron Lummer which whiles away most of the first act until the fatal letter arrives. It's a balance wryly observed in this production, where Bader's Christine talks to a photograph of her husband on the dining table but is not averse to clasping hands with Nicky Spence's resonant charming oaf Lummer (pictured below on the toboggan run with Bader's Christine) at a distance; when hubby returns late in Act II, their entwining of fingers takes place at closer quarters on a smaller table for two.

The approach is of a still-underestimated originality. In the opera’s 14 scenes, Strauss reaches the apogee of the conversational style he had first unleashed in Der Rosenkavalier; while in the interludes he plumbs the depths of the characters’ psyches. Too trivial a subject for so weighty a burden? The composer thought not, wondering if anything could be more serious than married life, and even Rosenkavalier poet-librettist Hugo von Hofmannsthal, who had shuddered at the initial proposition, leaving Strauss to write the libretto himself, had to admit that the depths had been plumbed with admirable integrity. It’s true that the score is a bit like a clever, affectionate spaniel that wants to lick you all over in the first act, and then breeds a legion of hysterical puppies in the second, but if you relish that, as Scottish Opera music director Francesco Corti so exuberantly and yet professionally did, it works.

The approach is of a still-underestimated originality. In the opera’s 14 scenes, Strauss reaches the apogee of the conversational style he had first unleashed in Der Rosenkavalier; while in the interludes he plumbs the depths of the characters’ psyches. Too trivial a subject for so weighty a burden? The composer thought not, wondering if anything could be more serious than married life, and even Rosenkavalier poet-librettist Hugo von Hofmannsthal, who had shuddered at the initial proposition, leaving Strauss to write the libretto himself, had to admit that the depths had been plumbed with admirable integrity. It’s true that the score is a bit like a clever, affectionate spaniel that wants to lick you all over in the first act, and then breeds a legion of hysterical puppies in the second, but if you relish that, as Scottish Opera music director Francesco Corti so exuberantly and yet professionally did, it works.

From my seat towards the front of the stalls, with the orchestra jutting out beneath the stage, balances were a bit awry between voices and players; I felt Corti could have gone for a lighter touch in some of the one-to-ones, though his interludes were flawlessly vivid, and he brought out the heart and soul of Strauss’s loveliest tribute to his wife, the great "Dreaming by the Fireside" rhapsody. Praise be to Quetes for standing back and letting the purple and gold of the shimmering dropcloths do all the complementary work; my last experience of Intermezzo was David Fielding’s at Garsington, and that drowned the music out in cheap gags.

The basic premise as embodied in Manfred Kaderk's efficient designs is obvious but effective: Klimt’s lavishly costumed lovers of The Kiss (pictured left), locked in a passionate embrace, are torn asunder – as Robert and Christine are, first by physical distance, then by the threat of divorce proceedings – only to join again as the Storches slip off to the bedroom at the end and the maid listens at the door. The Art Nouveau designs dominate every interior, at times complementing the bourgeois villa where the action begins and ends, at others clashing with the seedy reality of the digs Pauline finds for her not-so-bright or promising student baron, and twice taking us to a none-too-realistic outdoors, first on a toboggan run and then to the Prater where a crazed Robert is not so quietly going mad at his wife’s inexplicable behaviour.

The basic premise as embodied in Manfred Kaderk's efficient designs is obvious but effective: Klimt’s lavishly costumed lovers of The Kiss (pictured left), locked in a passionate embrace, are torn asunder – as Robert and Christine are, first by physical distance, then by the threat of divorce proceedings – only to join again as the Storches slip off to the bedroom at the end and the maid listens at the door. The Art Nouveau designs dominate every interior, at times complementing the bourgeois villa where the action begins and ends, at others clashing with the seedy reality of the digs Pauline finds for her not-so-bright or promising student baron, and twice taking us to a none-too-realistic outdoors, first on a toboggan run and then to the Prater where a crazed Robert is not so quietly going mad at his wife’s inexplicable behaviour.

Here Strauss tries – and rather overdoes – a parallel with the cosmic storm of his previous, massive fairytale opera Die Frau ohne Schatten; and in fact the novel breaking-up of the stage as well as the fin-de-siècle luminosities reminded me of nothing so much as another dream-world, the Peter Stein production of Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande. That's the first great opera with extensive interludes, a mythic portrait this time of an unhappy marriage. Was Strauss aware of the parallels and at times having a little parodistic fun at their expense? Who knows? The main thing is that all the characters, from the smallest to the toughest, should be believable, and though it looked on paper as if Scottish Opera would not be using much homegrown talent, its young artists – Rebecca Afonwy-Jones and Michel de Souza, last seen in the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama's Prokofiev War and Peace – take smart cameos stylishly.

The funniest performance comes from Jeremy Huw Williams's card-playing Councillor of Commerce, a man far more neurotic and troublesome than he imagines his beloved conductor’s wife to be, though with a good conscience; and there’s beautiful, baby-tenor phrasing from this new Spence who sounds as if he might well match Toby as a fine Britten singer. Sarah Redgwick makes a wise, Germanically fluent maid (Anna, the name of the Strauss's trusty servant, who despite Pauline's tantrums was still with them in their old age). It’s the trio of Bader, Wood and Corti, though, which walks off with the purple passages, and as the married couple's not-too-saccharine duet of reconciliation soars, so do our spirits at the end of an act which can pall without this level of focused energy. Well, mine certainly did, for I’m sure this is a piece which is hated as much as loved. All it takes is a little understanding, and that this straightforward but vivacious evening shows to the hilt.

OVERLEAF: MORE RICHARD STRAUSS ON THEARTSDESK

Ariosto’s epic poem Orlando Furioso has yielded more than its fair share of operatic spin-offs. Inspiring three operas apiece from both Handel and Vivaldi, as well as works from Lully, Haydn, Caccini and Rameau, its vivid stories of love, magic and revenge were plundered freely by composers for the better part of two centuries. It’s a rich seam of works, and one the Barbican is celebrating with a triptych of concerts. We’ve already had an exceptional Alcina from Minkowski and Les Musiciens du Louvre, and Il Complesso Barocco will present Ariodante in May, but last night it was the turn of Jean-Christophe Spinosi and Ensemble Matheus with Vivaldi’s Orlando Furioso.

Wars have no end. Soldiers may come home, battlefields may be vacated, peace treaties signed, but scars remain. The violence of combat has a way of revisiting itself on the victors and vanquished and ravaging soul and state.

Without the definite article, what kind of a Flute is Peter Brook's - beyond, that is, the literal manifestation of a stick on a string that makes no soothing noises? Best describe it as a crescent moon of a version, loosely based on Schikaneder's text with less than half of Mozart's music and matching slivers of voices, attached to mostly fledgling stage presences. The diminishing returns of Brook's operatic deconstructions, from the bold Tragedy of Carmen through the more seriously compromised Impressions of Pelléas, here reach a dead end in a kind of bleached purgatory.

A highlight of the London Handel Festival’s annual season is the opera, generally chosen from one of the dustier, more spidery corners of the composer’s repertoire. What a surprise then to see Rodelinda taking its turn this year. An undisputed classic, it’s also the opera that played perhaps the biggest part in reviving Handel’s fortunes on the stage in the 20th century. With aria after aria of generous and dramatic vocal writing and plenty of crowd-pleasing numbers, it’s also a natural showcase for the young singers of the Royal College of Music – perhaps the only ones having more fun than their audience last night.

Trying to introduce children to classical music is a tricky business. The benchmarks are still Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf and Poulenc’s Babar – both characterised by witty, quirky music and strong storylines. Opera is a harder sell – there’s the slowness of it, the sheer lunacy of characters striding about on stage expressing their inner feelings at full volume, accompanied by a 70-piece orchestra. So credit is due to Opera North’s education department for commissioning Errollyn Wallen’s Cautionary Tales! in response to requests for family-friendly opera.

What kind of Aida would you prefer: one in which singing actors stretched to the limits find Verdi's human volcano of emotions beneath the cod-Egyptian rubble, or a stand-and-deliver production with a stalwart cast of beaten-bronze voices? Having had a taste at least of the former once in my life, I wasn't very happy to succumb to the latter in this Covent Garden revival. It was the wall of sound in the big Act II ensemble which made me at least willing to be convinced.

Let's begin at the end. Isn't the nuns-to-the-scaffold scene which concludes Poulenc's ultimate testament of doubt and faith the deepest, most heart-wrenching finale in all opera? It even has the edge over Richard Strauss's Rosenkavalier trio and duet, in that the singers often end up in tears as well as the audience. If my eyes were dry at the end of the Guildhall School's valiant staging, that's not because the production lacked the necessary clarity, imagination and motion, nor was it due to any dearth of good voices. But clearly something wasn't quite right.