“So then I go and I make another cup of coffee and two pieces of toast with raspberry jelly and now I’m going to call Allen Ginsberg at exactly noon. Because he does his meditations and they told me to call him either at 11 at night or after 12.”

On 18 December 1974, Peter Hujar photographed Ginsberg for The New York Times, his first commission from the paper. The meeting with Ginsberg – it’s a tough assignment, Ginsberg never warms up and when Hujar develops the film he says there was “no contact there” – is just one part of the day that he describes in minute detail on 19 December to his friend Linda Rosenkrantz. It’s part of a tape-recorded project she’s developing (Chuck Close was her first subject), “to find out how people fill up their days, because I myself feel like I don’t do anything much all day.”

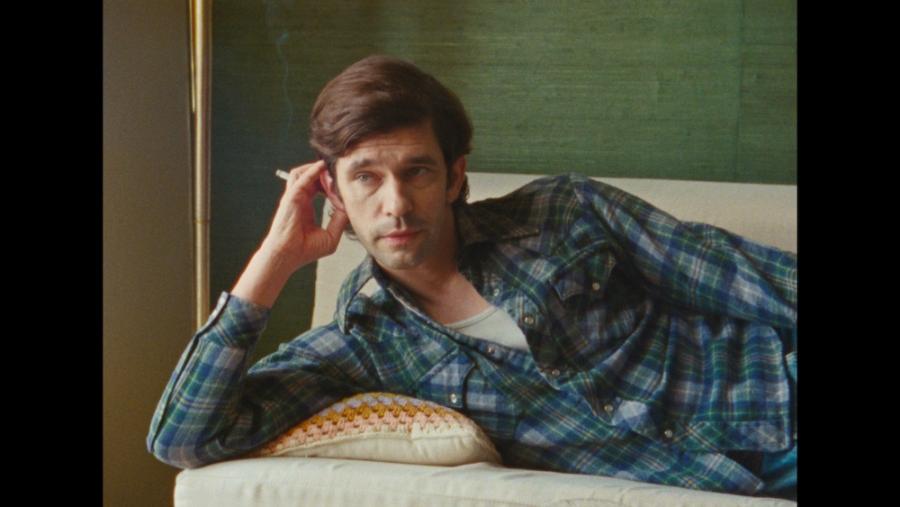

Director Ira Sachs stays close to Rosenkrantz’s transcript, which she recently rediscovered in her filing cabinets and donated to the Morgan library in New York; it was published as a book in 2022. It’s an elegant, unusual film, a two-hander starring Ben Whishaw, continuing his collaboration with Sachs after Passages, as Hujar. Rebecca Hall is Rosenkrantz and both are brilliantly cast (even though they’re Brits).

It brings to life Hujar’s circle of downtown artists and writers, some famous, such as Fran Lebowitz, Susan Sontag, Janet Flanner, some forgotten, as well as revealing his charismatic character and enhancing his reputation as an important photographer. There’s some discussion of money and getting paid and how Hujar isn’t much good at organising his invoices. “I’m really trying very hard to be a businessman.” In 1987, aged 53, he died, penniless, of AIDS, and his work, mainly black and white portraits, only became widely recognised posthumously.

The film is confined to Linda Rosenkrantz’s apartment and Sachs worried at first about the static quality of what he’d taken on. “The text,” he said, “was exactly the opposite of what interests me most in film, which is movement and action and cinema.” He’d set up something that had inherently none of the above. But somehow, with Alex Ashe’s cinematography and the clever use of light and space, it works.

The two protagonists move from the dining-room table, to the bed, to the balcony, sometimes dancing to a record (Hold Me Tight by Jim McDonald), which provides a break and release, sometimes drinking or watching the sunset, with four costume changes along the way. Sometimes the camera lingers on Whishaw’s face, sometimes on Hall’s, with the focus blurring and changing.

Just two old friends talking about people they both know, but Whishaw’s expressive voice (even though his tone is often flat, or deadpan: “Is it boring?” he asks at one point) and Rosenkrantz’s mischievous responses turn 76 minutes into something very particular. Their love for each other shines through. Linda worries about Hujar’s diet – you don’t eat enough, that’s why you need to take so many naps, she tells him. And you put too much energy into smoking. “It upsets me.” He agrees. “I wish I could stop. I don’t feel good.”

The Ginsberg meeting forms the crux. Hujar is not sure what to wear: Ginsberg lives down on the Lower East Side on 10th Street between Avenues C and D while Hujar lives on 12th Street and Second Avenue (now luxury apartments above the Village East by Angelika cinema) in the slightly less funky East Village, “which suddenly doesn’t quite make it.” He had thought of wearing his long coat but decides, “I’d be much snazzier in my red ski jacket.” “Better choice,” agrees Linda.

When he arrives at Ginsberg’s place - “the most run-down tenement” - Peter Orlovsky, Ginsberg’s longtime partner, opens the door. “His hair is still down the back of his neck, like he’s 45 years old but he’s like an old Polish man.” Ginsberg is cool and unfriendly, suspicious of Hujar. They go out to take the photographs at a burned-out butcher shop window that, Ginsberg tells him, was the Peace Eye Bookstore. Ginsberg stands there chanting, “ummpatumpum” as rendered by Hujar, then crosses the street and sits in the lotus position. “He’s a compulsive chanter,” says Linda. All Ginsberg wants to talk about, says Hujar, is who really runs the country, the top ten corporations, and the Times’s connections with oil interests. “And I couldn’t care less.”

Ginsberg warms up a bit when Hujar reveals that he’s going to photograph William Burroughs. “Suck his cock,” he suggests. “So different from the chanting image,” remarks Linda. “Yeah,” says Hujar. “He took a certain relish in being naughty.” They both bitchily agree that Burroughs, unlike Ginsberg, will age well.

Later Hujar’s friend, the critic Vince Aletti, arrives and they order Chinese from the Jade Mountain on Second Avenue, where Hujar, as he waits for his order – moo goo gai pan and sweet and sour pork, $7.43) – closely observes another customer drawing squares on a restaurant calling card. He looks sort of fat but “he has a very nice face, there’s something sort of lonely and strange – he looks very much like an unmarried man, straight, of 35.”

“All I did was spend two hours with Ginsberg,” muses Hujar. “This takes a day?” His last action is to go to the window to watch the whores in the street down below, talking so loudly they’ve woken him up. As the film closes to Mozart’s Requiem, Peter Hujar’s day is over, but decades later it lives on.

Add comment