The incendiary topic of Egyptian-American director Lotfy Nathan’s debut feature Harka is poverty and corruption in Tunisia a decade after the failed promise of the Arab Spring.

The word harka in the local Arabic dialect means either “to burn” or “to emigrate illegally”, and both definitions refer to the sad story of Ali Hamdi (Adam Bessa), an unlicensed petrol vendor on the streets of Sidi Bouzid. This is the desert city where, in 2011, a real-life barrow boy by the name of Mohamed Bouazizi literally ignited the country’s Jasmine Revolution with a symbolic act of self-immolation following persecution by the local authorities.

“The police steal from me every day, the bank repossessed our home,” says Ali, whose downward spiral is loosely based on Bouazizi’s. “There is so much injustice I’m losing my mind.” Nathan’s anguished tale also owes something to the narrative principle of Chekhov’s Gun. (“In act one, if a pistol is hanging on the wall,” the Russian playwright wrote, “then it should go off in act three.”)

We first meet Ali plying his illegal trade in the rush-hour traffic, filling up motorists’ tanks and paying kickbacks to hatchet-faced cops. In addition to dealing in contraband petrol, Ali is also a chain smoker. Cinematographer Maximilian Pittner’s deft camerawork seems to foreshadow a tragic denouement as it lingers on fuel canisters and wreaths of cigarette smoke. A beautiful sequence set in the bus station picks out a red fire-extinguisher hanging on the pastel blue wall of the ticket office.

We first meet Ali plying his illegal trade in the rush-hour traffic, filling up motorists’ tanks and paying kickbacks to hatchet-faced cops. In addition to dealing in contraband petrol, Ali is also a chain smoker. Cinematographer Maximilian Pittner’s deft camerawork seems to foreshadow a tragic denouement as it lingers on fuel canisters and wreaths of cigarette smoke. A beautiful sequence set in the bus station picks out a red fire-extinguisher hanging on the pastel blue wall of the ticket office.

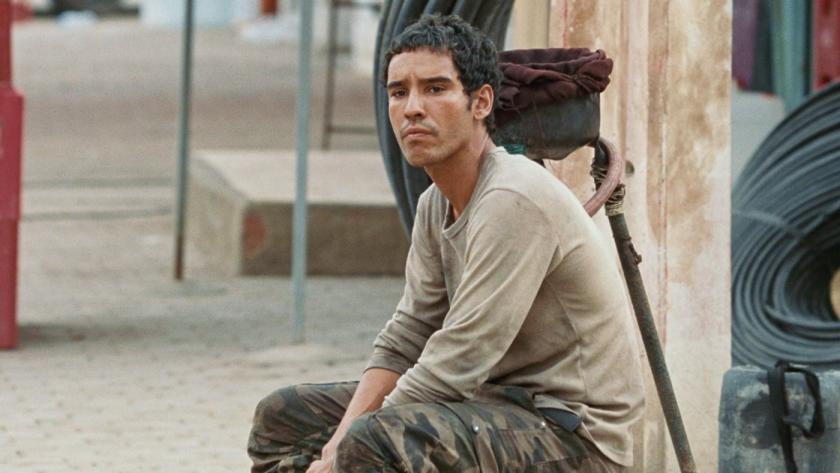

The best thing about Harka is Bessa’s mesmerising performance as a despondent victim fuelled with rage at the government and burning from the inside out. He dreams of leaving his impoverished life behind and escaping across the Mediterranean to Europe but just as migration looks like becoming a reality, the death of Ali’s father means he has to support his two sisters, the teenager Alyssa (Salima Maatoug) and the slightly older Sarra (Ikbal Harbi), who works as a maid in a posh house with a swimming-pool. (Pictured above: Harbi, left, and Maatoug)

Debts, bureaucracy, and police corruption, but also the proximity of wealth – Ali’s brother Skander (Khaled Brahem) has fled to the coast where he works as a waiter in a luxurious tourist resort – finally pushes Ali to his limits. In a desperate bid to make some fast cash, he undertakes a dangerous fuel-smuggling trip to the Libyan border, but loses his illicit cargo in a police raid, then winds up in jail when he doesn’t have the money to pay off the cops.

In the hands of a more visceral director, someone like Ken Loach perhaps, this slow demolition of an ordinary person, who falls through a crack in society, might have felt less didactic and exploitative. Unfortunately, Nathan’s script lays it on a bit thick with the doom and despair, and lacks subtlety or nuance.

Nevertheless, the final sequence in which Ali self-immolates outside the governor’s mansion, while traffic and pedestrians pass by seemingly oblivious to the orange flames of a burning man, is awesome and awful in equal measure.

Add comment