Two Neapolitans are wrestling for Italian cinema’s crown. Paolo Sorrentino and Matteo Garrone’s rivalry was for a time so personal that, though they were neighbours, they didn’t speak for years. Such foolishness was fleeting, and, while Garrone followed Gomorrah’s exposé of their gangster-ridden city with diverse and mesmerising fables such as Tale of Tales, Sorrentino has flourished on a more international scale.

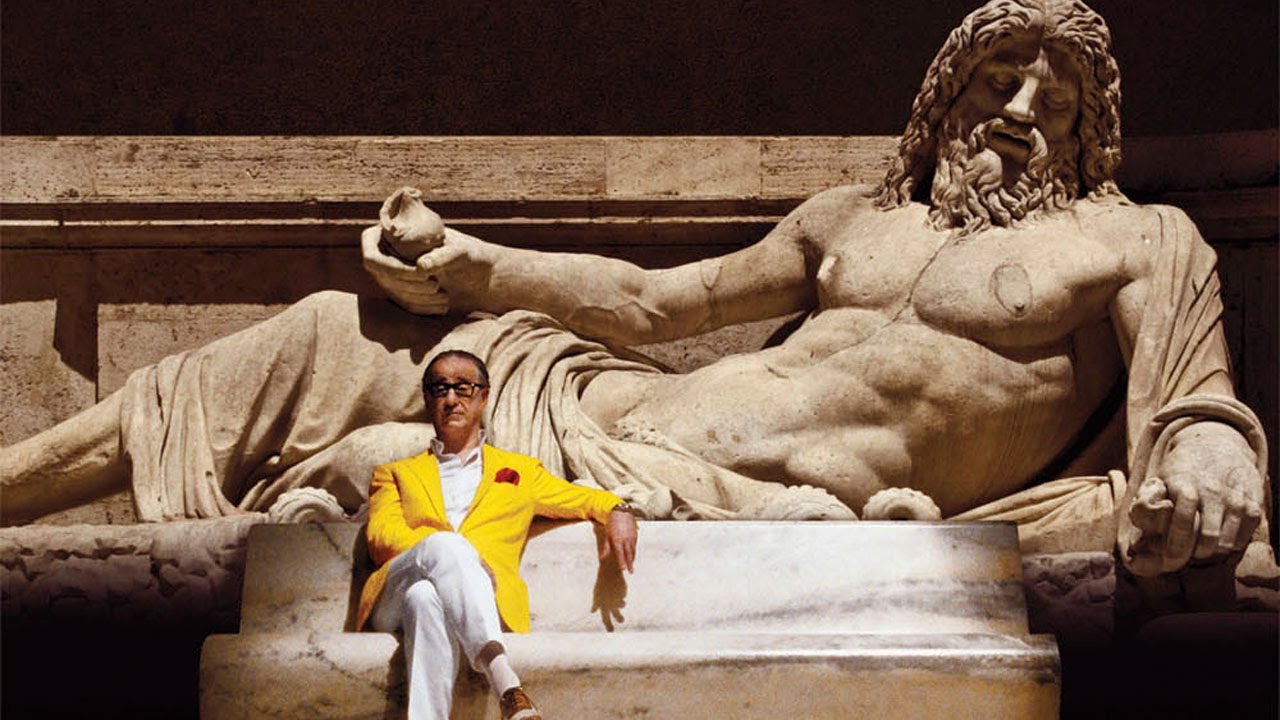

Sorrentino’s early successes were with Toni Servillo, a volcanic presence in Neapolitan theatre who he reduced to a thin-lipped chill as the Mob accountant undone by emotion in The Consequences of Love (2004), and reptilian flickers of feeling in Il Divo (2008) as Giulio Andreotti, Italy’s frequent Prime Minister between 1972 and 1992 as extremism was stoked by Machiavellian hands. “I do like to explore relationships of power, as most human relationships are poisoned by it,” Sorrentino told me after Il Divo had won Cannes’ 2008 Jury Prize. “This is my ultimate film in that sense. Because this one goes straight to the core of the problem, without any metaphors at all. For this reason, it won’t be easy to make the next film. I’ve said the last word on the subject that interested me. I’ve made four films now, and that seems enough…[The Battle of Algiers’] Pontecorvo made four films, and he was a great director…” In fact, the gentle 37-year-old I met then was already exploring Texas locations and learning English, to direct Sean Penn as a Robert Smith-like, fright-haired rock star who pursues an old Nazi in This Must Be the Place (2011). He returned to the Italian language and Servillo for The Great Beauty, a dissection of wasting decadence in the upper reaches of his new home, Rome (Toni Servillo pictured in The Great Beauty, above). The gaudy high style and operatic use of pop which made all these films so attractive was then held in check for Youth. Instead, he focused on the words of a somewhat contorted English script, and his veteran stars’ iconography, with Caine evoking his Swinging London prime. “All my films are in some way influenced by English films,” Sorrentino told me in 2009. “When I did The Family Friend [2006, about a troll-like loan shark betrayed by love] it was influenced by Mike Leigh’s Life Is Sweet. And without Stephen Frears’ The Queen, I don’t know how I could have made Il Divo.”

In fact, the gentle 37-year-old I met then was already exploring Texas locations and learning English, to direct Sean Penn as a Robert Smith-like, fright-haired rock star who pursues an old Nazi in This Must Be the Place (2011). He returned to the Italian language and Servillo for The Great Beauty, a dissection of wasting decadence in the upper reaches of his new home, Rome (Toni Servillo pictured in The Great Beauty, above). The gaudy high style and operatic use of pop which made all these films so attractive was then held in check for Youth. Instead, he focused on the words of a somewhat contorted English script, and his veteran stars’ iconography, with Caine evoking his Swinging London prime. “All my films are in some way influenced by English films,” Sorrentino told me in 2009. “When I did The Family Friend [2006, about a troll-like loan shark betrayed by love] it was influenced by Mike Leigh’s Life Is Sweet. And without Stephen Frears’ The Queen, I don’t know how I could have made Il Divo.”

Harvey Keitel’s ageing film director in Youth meanwhile plans one last great capstone to his career, only to be informed he lost his talent long ago (Keitel pictured with Michael Caine right). Sorrentino was revisiting the idea he’d mused on when we met, that you have to know when to stop. Instead, he worked on Youth in parallel with writing and directing all 10 hour-long episodes of The Young Pope. This project brought his talent into the heart of the international marketplace, and proved he was far from done with examining power. It finds Jude Law’s American cardinal Lenny over-promoted to Pope almost by mistake, wracked with doubt in God and himself, making an apocalyptic public address in demonic shadow, and veering between incompetence and vindictive calculation. This chaotic outsider with ultimate power has seemed timely since the US election. Yet Lenny stays somewhat sympathetic, not least because he is an orphan.

Harvey Keitel’s ageing film director in Youth meanwhile plans one last great capstone to his career, only to be informed he lost his talent long ago (Keitel pictured with Michael Caine right). Sorrentino was revisiting the idea he’d mused on when we met, that you have to know when to stop. Instead, he worked on Youth in parallel with writing and directing all 10 hour-long episodes of The Young Pope. This project brought his talent into the heart of the international marketplace, and proved he was far from done with examining power. It finds Jude Law’s American cardinal Lenny over-promoted to Pope almost by mistake, wracked with doubt in God and himself, making an apocalyptic public address in demonic shadow, and veering between incompetence and vindictive calculation. This chaotic outsider with ultimate power has seemed timely since the US election. Yet Lenny stays somewhat sympathetic, not least because he is an orphan.

He shares this status with Sorrentino, whose parents died in an accidental gas explosion at their flat when he was 17. “The loss of my parents changed my life in every sense,” he has said. “If it hadn’t happened, I would never have become a director. I was the son of a banker and I would have followed in his footsteps. Becoming an orphan gave me the recklessness to try it.”

At the age of 46, Sorrentino’s gamble has paid off handsomely. But when our latest interview takes me to Rome for 48 hours, it’s for a footnote in his career. Killer In Red is a 20-minute film noir made for Campari, intended to expand its famous calendar-based ad campaigns. Continuing the director’s English fetish, Clive Owen stars as both a contemporary barfly and an Eighties bartender, with the latter seduced to probable murder by the titular femme fatale (played by Swiss model Caroline Tillette, pictured below with Clive Owen). Journalists of seemingly every sort and nation have been flown to Rome to view this, early one Tuesday morning. Owen takes questions with the director afterwards. In truth, the short lasts long enough to show Sorrentino’s weakness for stilted, presumably assisted English scripts (which hobbled Youth, but not The Young Pope) and under-dressed, gorgeous young women. “At the centre of male desire is always the femme fatale,” he explains through a translator of Tillette’s casting, and skimpy red cocktail dress and swimsuit. “We picked her purely according to the rules of [the film noir] genre. She is there to devastate the male desire. She was perfect for that.” The short’s barroom milieu also appealed. “I remember spending much of the Eighties in bars,” he reminisces. “Those were the days, when people like me didn’t do much except spend time in bars…”

In truth, the short lasts long enough to show Sorrentino’s weakness for stilted, presumably assisted English scripts (which hobbled Youth, but not The Young Pope) and under-dressed, gorgeous young women. “At the centre of male desire is always the femme fatale,” he explains through a translator of Tillette’s casting, and skimpy red cocktail dress and swimsuit. “We picked her purely according to the rules of [the film noir] genre. She is there to devastate the male desire. She was perfect for that.” The short’s barroom milieu also appealed. “I remember spending much of the Eighties in bars,” he reminisces. “Those were the days, when people like me didn’t do much except spend time in bars…”

“I am very lazy, and I pretend not to speak English [to you],” Sorrentino also cheekily admits, when asked how he directed Owen. This becomes less amusing when he continues in his comfortable native tongue later that day, as the world’s press line up for a gruellingly functional interview junket. If it’s 3.42, it must be our man from Brazil; and at 3.52, here’s Argentina. With translation, each 10-minute interview is effectively five. By the time I’m ushered into his hotel room, Sorrentino has been selling his lavish drinks ad with this industrial mode of conversation for most of the day. He’s up and pacing restlessly at first, before taking his seat. “I’ve been sitting for hours,” he explains in galling English. “So now I’m walking around…” The stopwatch ticks, and we talk.

NICK HASTED: Thinking of the genre of Killer in Red, are you well-versed in film noir and crime fiction? Are they things that you love?

PAOLO SORRENTINO: As a viewer, definitely that’s the genre that I’m keenest on. One of the movies that I keep watching over and over again is Chinatown – just to give you an idea. So because as a spectator I enjoy the genre, and because I’m lucky enough to be a film-maker, while I was given this great opportunity to stick my foot into it, I took it.

With a sponsor for this film, does that make you feel any less free? Could you make a feature film, or a TV series, in these conditions?

Listen, let’s call a spade a spade. In advertising, you are less free, okay. But sometimes you get lucky enough, in advertising, to find clever people with whom you think there could be a shared way of going about things. And this was one of those times.

I watched the first few episodes of The Young Pope before I came here, and it seems to have become prophetic. Lenny and Donald Trump are very different characters, of course (Jude Law pictured in The Young Pope below). But do you see parallels? And is part of your interest in Lenny to explore someone who gets more power than he’s capable of using?

What I really wanted to do was explore those people, and there are many among people in power, who abuse their power, due to certain flaws in their character or personality. This could be Trump’s case, I’m not sure. It could be. But that’s the only kind of analogy I can imagine – for now. One of the cardinals says in The Young Pope: “As an orphan grows older, he may discover a fresh youth in him.” Is that a line from the heart? Have you experienced that fresh youth?

One of the cardinals says in The Young Pope: “As an orphan grows older, he may discover a fresh youth in him.” Is that a line from the heart? Have you experienced that fresh youth?

[Sorrentino snaps into focus at this, weariness shaken off] Never mind me, and my experience. I think it often happens that if you’re orphaned as a young person, you’re basically violated in your youth, and you’re compelled to grow very fast. Very fast. And you lose your youth. There are times when you can recover it. That’s the thing that I was thinking about.

Harvey Keitel’s director in Youth is an interesting character for you, I would think. Do you share his interest in the legacy you might leave as a film-maker, and the shape of your career?

No! [laughing, honestly amused] This is a typical question that would arise in the mind of one of those film-makers who take themselves very seriously. I do not belong to that school!

Was there any sense of imagining a possible future there – thinking of yourself later as a director?

Ah, yes, yes. Perhaps the character does in fact reflect fears that are my own. I had Harvey Keitel do things that I hope not to do in the future. It’s a warning to myself, if you like – do not insist, as you grow old, in making movies. Movie-making’s for younger people.

You say that now, Paolo…

But I’m hoping I still say that when I grow older!

With the wider audiences and range of actors that you’ve had with Youth and The Young Pope, would it seem a backward step at the moment to go back to Italian-language films?

[The time-up signal is given, and Sorrentino stretches in his seat, already storing up some rest before the next interview] No, actually, if you think that The Great Beauty had more viewers than Youth, and it was an Italian-language movie. I don’t think language carries any decisive weight. I think the rule of the game here is to do what you feel like doing, both in your profession and in your life, and forget about how large the audience is. Thank you…

The director is immediately back on his feet, the end of his line of inquisitors almost in sight. He has one more duty, at the lavish premiere of Killer in Red that night, for which the imperial-pillared, 19th- century Palazzo delle Esposizioni is decked in red. He and his cast take a bow, their employer’s cocktails copiously flow, and models incongruously go-go dance for a while. What with one thing and another, as I blearily glimpse the Colosseum from my airport cab the next day, my tourist time off lasts 10 seconds.

Add comment