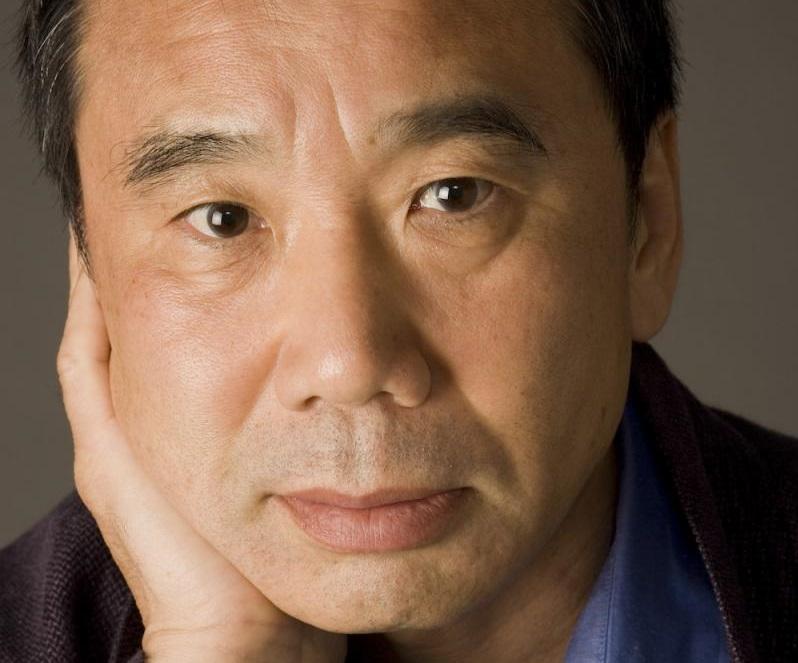

“I was a lamprey eel in a former life,” says a woman in “Scheherazade”, one of the most intriguing of the seven stories in Men without Women - it was previously published in the New Yorker, as were four of the others in the collection. Murakami is at his best when describing the extraordinary in his precise, simple prose (translated brilliantly by Philip Gabriel and Ted Goossen) and making it feasible. Scheherazade – the name given her by Habara, the mysteriously imprisoned man she looks after and has sex with – not only remembers her previous life as a lamprey – “fastened to a rock, swaying invisibly among the weeds, eyeing the fat trout swimming by” – but also what it was like in the womb. An all-knowing, mysterious female image, and one that finds echoes throughout this slightly uneven collection.

Most of the stories touch on Murakami’s familiar themes: loneliness, infidelity, time, the strange ways people are intertwined. On the whole, the men have either lost a woman or are about to do so, though in “Samsa in Love”, a new take on Kafka where a creature wakes up one day as Gregor Samsa, there's unexpected joy: a young hunchbacked woman makes Samsa feel “warm inside” and glad to be human, even though he’s not sure what being a human means. Who had he been before? And was this thing – this preposterous body - really him? In “An Independent Organ” a middle-aged cosmetic surgeon who’s always had several girlfriends on the go falls in love for the first time and starts wondering, “Who in the world am I?” Who would he be if stripped of his career and his rights, as the Jews were by the Nazis? This questioning doesn’t lead him to a revelation but to self-erasure.

It’s a relief, after a fair amount of such chilliness, to meet Sheherazade, who’s very much alive. She’s middle-aged, unglamorous, but tells enthralling stories (hence her name) during her twice-weekly visits to Habara. She keeps him hanging on for the next instalment of the story of her teenage obsession with a boy, which drove her to break into his house when everyone was out. There she would sit on the floor, keep absolutely still, and let “cloudy but very pure” lamprey thoughts wash over her before stealing his pencil or T-shirt. The teenage passion she describes is conspicuously lacking in her relationship with Habara. She stocks up his fridge efficiently and has sex with him in the same “deft, business-like” way. Yet Habara feels connected to her, even if only by a slender thread, and is, of course, frightened about losing her.

This slender thread between men and women links the stories, though sometimes it's all a bit too abstract and post-modern. In the last one, “Men Without Women”, a woman kills herself. Her husband informs the narrator, her ex-lover, in a late-night phone call. He looks back on their time together and the pain he felt when she left him after two years. Tragic, but then we find out that she was the third woman he’d gone out with who’d killed herself. Why? We never know. There’s an abyss of sadness – he feels he’s the loneliest man on the planet, after the husband - but the characters are too unspecific to be satisfying.

This slender thread between men and women links the stories, though sometimes it's all a bit too abstract and post-modern. In the last one, “Men Without Women”, a woman kills herself. Her husband informs the narrator, her ex-lover, in a late-night phone call. He looks back on their time together and the pain he felt when she left him after two years. Tragic, but then we find out that she was the third woman he’d gone out with who’d killed herself. Why? We never know. There’s an abyss of sadness – he feels he’s the loneliest man on the planet, after the husband - but the characters are too unspecific to be satisfying.

“Kino”, on the other hand, is packed with everyday detail about the transformation of a coffee shop into a bar – the wallpaper, the Thorens turntable and the Luxman amp, the old jazz collection - combined with Murakami’s genius for the magic lurking beneath the surface of things. Here he's on top form. There’s a supernatural stranger, a snake invasion, a woman with cigarette burns all over her body and an old willow tree. Somehow they’re all connected, as is Kino’s final realisation that yes, he was deeply hurt by his ex-wife’s affair though he’d felt nothing much at the time. “'Don’t look away, look right at it," someone whispered in his ear. “This is what your heart looks like.”' And Kino, like the other men without women, is grateful for being able to weep, and for silence, and for demons who leave him alone, however temporarily. Small mercies.

- Men Without Women by Haruki Murakami (Harvill Secker, £16.99 hardback and e-book)

Add comment