There are some wonderful things in this exhibition, and that’s no surprise: the British Empire endured for over 500 years and at its peak extended across a quarter of the world’s land mass. Preparing an exhibition of corresponding reach must have involved considering a vast range of objects, but choosing well is another matter entirely. Severely overfilled, this is a show hampered by too broad a scope, but also by the sensitive nature of its subject; in its eagerness to present points of view other than that of the British colonists, there is a crippling reluctance to omit anything at all.

So it is that the first room, devoted to maps and map-making, feels like a statement of intent, getting in its condemnation of the British in advance of the many paintings we are about to see that glorify them. Crucial as they are to the business of empire-building, these maps are also raw representations of conquest, serving not only a practical purpose but an ideological one. It was through maps that indigenous place names were brutally and formally erased, and they provided a cheap and easily distributed means of hammering home the might of the British Empire across the globe, in schools, public buildings, homes and offices. Maps can be beautiful things, but here they act rather like a visual disclaimer for what is to follow.

You can see exactly why such a caveat might have seemed necessary the moment you step foot in the next room, which bursts with glorious, exotic riches pillaged from far-flung lands. Centuries on, it is all still rather close to the bone, for in this dazzling array of botanical drawings and collected drawings is the same spirit that has shaped so many of our museum collections. Stubbs’ A Cheetah and a Stag and Two Indian Attendants, c. 1764, on loan from Manchester Art Gallery, is the crowning glory, and encapsulates the sense of wonder and excitement of the British at the expansion of the Empire (main picture).

You can see exactly why such a caveat might have seemed necessary the moment you step foot in the next room, which bursts with glorious, exotic riches pillaged from far-flung lands. Centuries on, it is all still rather close to the bone, for in this dazzling array of botanical drawings and collected drawings is the same spirit that has shaped so many of our museum collections. Stubbs’ A Cheetah and a Stag and Two Indian Attendants, c. 1764, on loan from Manchester Art Gallery, is the crowning glory, and encapsulates the sense of wonder and excitement of the British at the expansion of the Empire (main picture).

One of the most impressive, but simultaneously shocking rooms deals with history paintings made to commemorate and glorify British conquests overseas. For the most part these paintings serve to add a veneer of British decency to episodes of barbarity, and in Robert Home’s The Reception of the Mysorean Hostage Princes by Marquis Cornwallis, 26 February 1792, c.1793, the British soldiers taking two little boys prisoner appear as amiable as kindly uncles. In shocking contrast is Edward Armitage’s vast painting Retribution, 1858, in which a fearsome Britannia slays a Bengal tiger. It was meant to hang in Leeds Town Hall, intended to stir up the vengeful anger of the British in response to the Cawnpore Massacre of 1857, in which over 100 British women and children were murdered.

As the Empire matured, relations between colonist and colonised inevitably became more complex, and the second half of the exhibition struggles in vain to address and represent the different encounters and narratives of Britain’s colonial past. While the first rooms have a coherence that comes from presenting art from within the same western tradition, the multiple and varied cultures of the colonies can only be inadequately represented. At its height, the British Empire was so vast and the people within it so diverse that the attempt could hardly be anything but tokenistic.

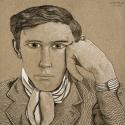

Nevertheless, some fascinating examples of the mingling of western and indigenous artistic traditions emerge, the carved figure of Queen Victoria made by a Yoruba artist in Nigeria, combining traditional wood-carving techniques with western portraiture (Pictured above right), while the European taste for romanticised portraiture found new, exotic subjects in the colonies (Pictured left: Charles Frederick Goldie, Harata Rewiri Tarapata: A Maori Chieftainess, 1906).

Nevertheless, some fascinating examples of the mingling of western and indigenous artistic traditions emerge, the carved figure of Queen Victoria made by a Yoruba artist in Nigeria, combining traditional wood-carving techniques with western portraiture (Pictured above right), while the European taste for romanticised portraiture found new, exotic subjects in the colonies (Pictured left: Charles Frederick Goldie, Harata Rewiri Tarapata: A Maori Chieftainess, 1906).

Like almost every topic addressed here, the attempt to summarise the impact of non-western art on European artists in the 20th century really merits its own exhibition, while the examination of the legacies of empire would feel incredibly truncated were one actually capable of looking at anything more. This is an ambitious show that has overstretched itself; by trying to fairly represent every aspect of this long and complicated episode in world history, the whole endeavour lacks the gravitas it deserves.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment