For all the wrong reasons, the work of Dexter Dalwood serves as a useful metaphor for this exhibition. Trite, tokenistic and desperate to look clever, Dalwood’s paintings are as tiresomely inward-looking as the show itself, which is a dismal example of curatorial self-indulgence at the expense of public engagement. It’s not always a bad thing to give free rein to theorising curators, but this show compares unfavourably with exhibitions at, notably, the National Portrait Gallery, and the Courtauld Gallery that have successfully introduced the public to sound, but arguably arcane academic research that might otherwise have simply echoed around the ivory towers.

There’s nothing sound about this exhibition though, and its dubious thesis, insofar as there is one, is that history painting is not half as boring as we might think. The first room seems to push the genre to arm’s length, hoping perhaps to reassure us that it is not all about overblown narrative, and that some of it is actually rather radical and right on. Dominated by Dalwood’s The Poll Tax Riots, 2005 (main picture), and Jeremy Deller’s The History of the World, 1997-2004 (pictured below), the room is meant to confound our preconceptions but instead only draws attention to the show's second, equally fatuous, line of argument.

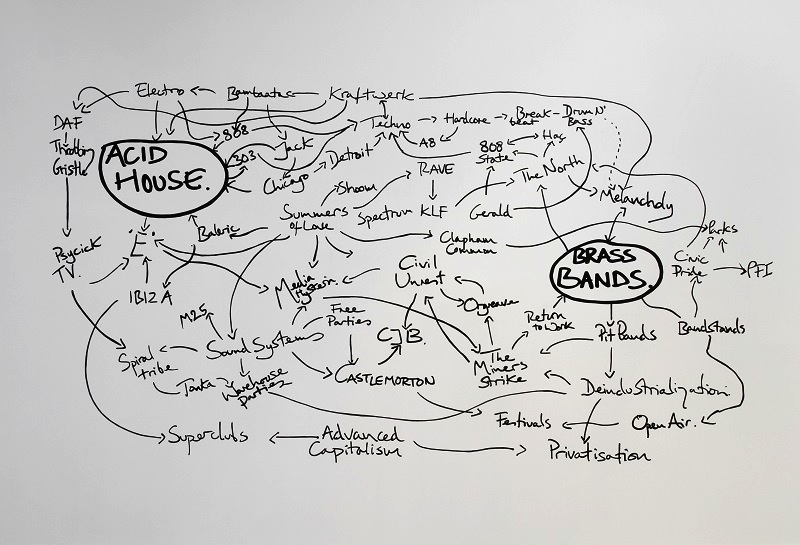

Jeremy Deller’s word map is not a history painting. It connects traditional brass band music to acid house, exploring the nature of history by suggesting the connections and points of confluence between these two apparently irreconcilable types of music. But its inclusion at the beginning of the show signals a surprising, and surely unjustifiable broadening of the definition of history painting to include anything that tackles a historical subject.

Jeremy Deller’s word map is not a history painting. It connects traditional brass band music to acid house, exploring the nature of history by suggesting the connections and points of confluence between these two apparently irreconcilable types of music. But its inclusion at the beginning of the show signals a surprising, and surely unjustifiable broadening of the definition of history painting to include anything that tackles a historical subject.

Propping up this bizarre decision is an unnecessary bit of quibbling over the definition of history painting, a genre that is surely quite easy to define. Didactic and preoccupied with grand narrative, showcasing the accomplishment and learning of the artist, it expounds themes from classical history or the Bible or immortalises pivotal, historically significant moments from the more recent past (Pictured below: John Singleton Copley, The Death of Major Peirson, 6 January 1781, 1783). History is used in the French, or Italian sense to mean narrative: what it is not about is the simple depiction of historical events. Clear this may be, but talking up a controversy over nomenclature conveniently allows the show to develop its pet theory, which is that baggily defined, history painting has flourished unabated since the 18th century.

Having dispensed with any meaningful parameters, all sorts of unlikely paintings become fair game, including Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s The Silent Greeting, 1889, pure sugary sentiment, in which a Roman soldier is seen leaving a bouquet of flowers on his sleeping lover’s lap. There’s no grand narrative here, and The Room in Which Shakespeare was Born, by Henry Wallis, 1853, however laden with meaning, is surely equally miscast as history painting.

Curiously enough, while plenty of unsuitable pictures are marshalled under the banner of history painting, perfectly usable examples of artists repurposing the genre have been overlooked. Ford Madox Brown’s Work, 1865, is not a history painting, but its large scale, and multiple representations of the body in a range of poses, exploit contemporary viewers’ knowledge and expectations of history painting in order to elevate and dignify its lowly and unconventional subject matter, the working man.

Curiously enough, while plenty of unsuitable pictures are marshalled under the banner of history painting, perfectly usable examples of artists repurposing the genre have been overlooked. Ford Madox Brown’s Work, 1865, is not a history painting, but its large scale, and multiple representations of the body in a range of poses, exploit contemporary viewers’ knowledge and expectations of history painting in order to elevate and dignify its lowly and unconventional subject matter, the working man.

There is a brief but essential diversion to acknowledge the influence of history painting on portraiture, but Turner – a figure famously well-represented in the Tate’s own collections – is barely here at all. And yet he not only produced any number of history paintings, he transformed landscape painting, elevating it to the status of history painting by imbuing it with gravitas and showing that it was capable of handling the most profound and edifying of themes.

Having failed to examine the ways in which the conventions of history painting were appropriated by other genres, the curators have sabotaged the climax to the show, which is Jeremy Deller’s The Battle of Orgreave Archive, 2001, a work which exists today as a collection of film and archive material documenting the epic re-enactment of this most notorious episode of the Miners’ Strike.

It just doesn’t sit well within this strange hotchpotch of paintings, and as such it is unconvincing as evidence of history painting, alive and well but reconfigured for the 21st century. In fact if this exhibition proves anything, it is that history painting is well and truly finished – Dexter Dalwood’s empty, contrived attempts to revisit the genre are ample proof of that.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment