Can you sense a person's life through a sequence of objects? Not to mention influence and legacy? Biographical exhibitions are fascinating, not least because they also tell us something about looking back through the filter of the present. And William Morris (1834-1896) has certainly been, in many ways, a man for all seasons.

Here the gifted design historian and biographer, Fiona MacCarthy, is the compiler in charge, providing an affecting look at a man whose sheer intelligence, combined with heartbreaking energy, determination and idealism, not only affected his world but went further in attempting to provide a template for how society should be. When he died, his doctor said simply he had died of being William Morris, worn out by effort.

This refined anthology provides in concentrated form a three-dimensional biography of Morris: writer, poet, designer, artist, craftsman, businessman, philosopher – and what came afterwards. What is brought out most strongly are his fiercely held politics – founder inter alia of The Socialist League, with no less a figure than Eleanor Marx among others, although Morris himself never ran for office, but rather promoted his ideas and ideals.

We see him here as an obsessively hardworking polymath whose influence still pervades our thinking

Morris’s engagement with society is made manifestly clear, even dominant, unlike the mammoth and indeed at times magnificent V&A exhibition in 1996 which shockingly relegated Morris’s political engagement to one obscure corner. In a Tory era, this is a quietly subversive exhibition: Socialist and Labour to the core.

We see him here, beyond the arts and crafts interiors, as an obsessively hardworking polymath whose influence still pervades our thinking about a huge variety of topics, from the place of design in society to our heritage and our treatment of the past and how it informs the present.

As so many reformers and idealists were and are, Morris came from a privileged background, his father successful in the City. He used his freedom from economic necessity to explore with prodigious energy his views of the greater good, translating idealism into action. And he did have at times to retrench: his business activities in the world of design and manufacture occasionally led to financial vicissitude.

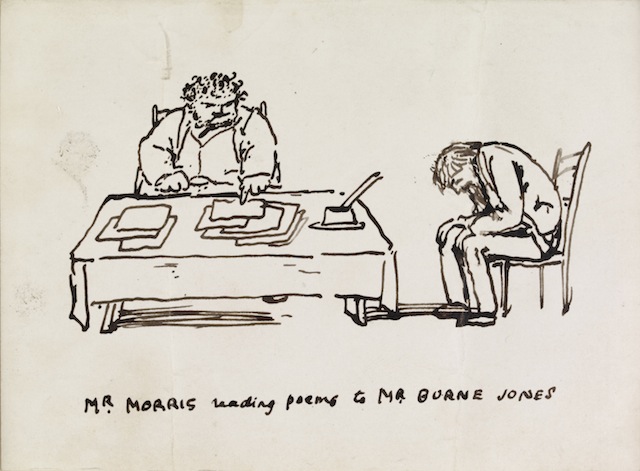

Throughout, his tenacious determination was constant. His daughter May Morris collected together 24 volumes of his published writings; a further two of his unpublished writings followed. He could easily be personally unaware: he turned down Oxford’s offer to be their professor of poetry, but there is a very affectionate caricature by Burne-Jones showing Mr Morris reading poems to Mr Burne-Jones (pictured below; 1886; © The Trustees of the British Museum); the relentless figure of the tubby poet, seated at a table with his book, is in sharp contrast to the slumped figure of the despairing listener. Georgiana Burne-Jones, wife to the painter, describes the inevitable problems of falling asleep while Morris recited.

We also have a little tour onscreen of Red House, the 1860 Philip Webb house designed for Morris in Bexleyheath. We are reminded that, after Oxford, where he met his life-long friends, including Burne-Jones, he thought to be an architect before he tried to become a painter. Success though came as a designer and a businessman, with his design firm promoting the well-made object, utilitarian or decorative – what he himself referred to as the minor art. These were the arts that made a difference, a substantial difference, to immediate domestic surroundings. Of course his most famous maxim was to “have nothing in your house that you do not know to be beautiful, or believe to be useful.” But even more, he did not, as he said, want “art for a few, any more than education for a few, or freedom for a few”.

We also have a little tour onscreen of Red House, the 1860 Philip Webb house designed for Morris in Bexleyheath. We are reminded that, after Oxford, where he met his life-long friends, including Burne-Jones, he thought to be an architect before he tried to become a painter. Success though came as a designer and a businessman, with his design firm promoting the well-made object, utilitarian or decorative – what he himself referred to as the minor art. These were the arts that made a difference, a substantial difference, to immediate domestic surroundings. Of course his most famous maxim was to “have nothing in your house that you do not know to be beautiful, or believe to be useful.” But even more, he did not, as he said, want “art for a few, any more than education for a few, or freedom for a few”.

Perhaps even more tellingly, considering his own rather tragic relationship with his working-class wife, there is his maxim for the good life of the individual: “Love and work – these two things only”. He admired those with the bravery to set up small utopian societies, visiting another reformer who came from a privileged background, Edward Carpenter, the “saint in sandals”, and visible here in a finely atmospheric portrait by Roger Fry.

On show we have not only a rare portrait of Morris himself – he detested being portrayed – by GF Watts, from 1870 (pictured below; © National Portrait Gallery), and a portrait photograph by Frederick Hollyer, but an equally accomplished portrait of Burne-Jones, also by Watts.

The exhibition is a colourful progression of documents, books, banners, jewellery, textiles, photographs, posters, furniture and paintings: objects and images that tell us of short-lived utopian communities and long-lived architectural interventions, radical political ideas and the finest of calligraphy, indicating a ferociously complex swirl of innovative and influential ideas turning into concrete, tangible action.

Morris’s ideas form a steady background, as we are shown in images and documents, the notions of garden cities and garden suburbs, led by the still relatively unsung “heroic simpleton”, in George Bernard Shaw’s inimitable phrase, Ebenezer Howard; and to Octavia Hill’s National Trust and Henrietta Barnett’s Hampstead Garden Suburb. Moving into the postwar period, when it seemed Britain could start anew, here are the logo and poster of The Festival of Britain, designed by Abram Games, that gallant and successful attempt to bring the best of contemporary society to as many people as possible, to banish the postwar blues, and to create a genuine sense of celebration; and, of course, we still have the Royal Festival Hall. The leading left-wing journalist and festival mastermind Gerald Barry is also shown in a charmingly dapper portrait by Norman Parkinson.

Morris’s ideas form a steady background, as we are shown in images and documents, the notions of garden cities and garden suburbs, led by the still relatively unsung “heroic simpleton”, in George Bernard Shaw’s inimitable phrase, Ebenezer Howard; and to Octavia Hill’s National Trust and Henrietta Barnett’s Hampstead Garden Suburb. Moving into the postwar period, when it seemed Britain could start anew, here are the logo and poster of The Festival of Britain, designed by Abram Games, that gallant and successful attempt to bring the best of contemporary society to as many people as possible, to banish the postwar blues, and to create a genuine sense of celebration; and, of course, we still have the Royal Festival Hall. The leading left-wing journalist and festival mastermind Gerald Barry is also shown in a charmingly dapper portrait by Norman Parkinson.

We also have a witty 1950s Ray Williams’ photograph of the young and handsome Terence Conran, frowning rather alluringly while at ease in one of his Cone chairs. Conran’s Habitat brought fine design into the orbit of those with modest budgets, thus fulfilling an aspiration even Morris had been unable to achieve. But Terence Conran (b 1931), with his Design Museum a lasting legacy, is the only living figure here; the 1960 cut-off date means that no one is revealed who might currently be such an idealistic entrepreneur. And, by the way, Morris, practicing what he preached, was also not only someone who had taught himself so many craft skills, including being able to embroider, he was also a good cook. As is Terence Conran.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment