As a self-taught chemist, innovative industrialist, a businessman who exploited and developed new means of distribution and marketing, an anti-slavery campaigner and a man dealing with his own disability, the Staffordshire potter Josiah Wedgwood was an important 18th-century figure, a pioneer whose achievements still resonate. But a genius?

The historian, biographer and author AN Wilson has no doubt about this. Presenting this perambulation through Wedgwood’s life and vessels, Wilson began in Burslem – “a muddy village in the middle of nowhere” – and climaxed in the royal palaces of continental Europe, an enviable trajectory which also showed Wedgwood as a consummate social climber.

Although not mentioned, The Genius of Josiah Wedgwood comes on the back of Wilson’s 2012 novelisation of the life of Wedgwood, The Potter’s Hand. A large part of the inspiration for that – and this documentary – was the fact that Wilson’s father, Norman, was a potter and production director at Wedgwood. Norman Wilson took his son into the factory where he became intimate with the business and gave him advice which still looms large in his life. More than the story of Josiah Wedgwood, this was also an autobiography and requiem for the now-defunct, once world-class company.

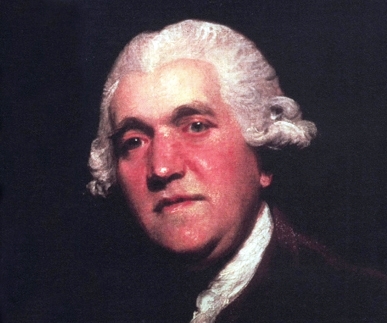

Wedgwood was an extraordinary figure (pictured right). Born into a potting dynasty in 1730, he had no access to high-level education, London, the gentry or nobility. Wilson described the Georgian-era village of Burslem being as it was in 1530. It’s doubtful the pre-Reformation settlement was comparable with its 18th-century self, especially as Staffordshire was not a centre of pottery manufacture then.

Wedgwood was an extraordinary figure (pictured right). Born into a potting dynasty in 1730, he had no access to high-level education, London, the gentry or nobility. Wilson described the Georgian-era village of Burslem being as it was in 1530. It’s doubtful the pre-Reformation settlement was comparable with its 18th-century self, especially as Staffordshire was not a centre of pottery manufacture then.

Wilson has a way with unsupported, seemingly authoritative statements that when pondered come unstuck. He declared that Wedgwood took “pottery from utility to luxury.” He may have with his products, but this was not a notable feat. From the 1750s onwards, the British porcelain industry was producing vessels costing the same as their counterparts in silver. Making luxury objects from clay was not an innovation.

In saying that Wedgwood gave up making imitations of Chinese porcelain, Wilson missed a vital point. Faux Chinoiserie was a part of the market which had to be addressed. Wedgwood’s rise to prominence in the 1760s and ‘70s was backdropped by a British pottery industry that made vessels in the style of Oriental wares: in home-grown delft and porcelain. Wedgwood had no choice but to follow this trend and did so with his brilliantly white wares, but his flair for marketing and expanding distribution networks killed off the former and undercut the latter. He was a ruthless entrepreneur and, as such, also helped establish Staffordshire as the home of British pottery. The cost was the closure of manufactories elsewhere. Also, the division of labour was neither new nor unique to Wedgwood, and had been employed in the British pottery industry from the late 16th century.

In saying that Wedgwood gave up making imitations of Chinese porcelain, Wilson missed a vital point. Faux Chinoiserie was a part of the market which had to be addressed. Wedgwood’s rise to prominence in the 1760s and ‘70s was backdropped by a British pottery industry that made vessels in the style of Oriental wares: in home-grown delft and porcelain. Wedgwood had no choice but to follow this trend and did so with his brilliantly white wares, but his flair for marketing and expanding distribution networks killed off the former and undercut the latter. He was a ruthless entrepreneur and, as such, also helped establish Staffordshire as the home of British pottery. The cost was the closure of manufactories elsewhere. Also, the division of labour was neither new nor unique to Wedgwood, and had been employed in the British pottery industry from the late 16th century.

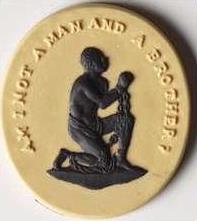

A man of his times, Wedgwood made opportunities. His social circle included thinkers, industrialists and inventors. They took from each other. He married into money. He successfully courted royalty and was granted the right to make a range called Queen's Ware. He played to the desires and aspirations of the emergent middle classes. He also had state-of-the-art housing constructed for his workers, valued and propagated education, supported American self-rule, was vociferously against slavery and distributed wares shouting this message (pictured above left: Wedgwood's anti-slavery medallion, with the legend "Am I not a man and a brother?"). Yet he exported to America and took the profit.

A risible comparison of the 18th-century industrialist to Apple’s Steve Jobs was a step too far into the indiscriminate. In choosing to sidestep the contradictions which define the undoubtedly complex Josiah Wedgwood in this unquestioning hagiography, Wilson took the easy path.

Add comment