'Why we understand each other': Peter Gill on The York Realist | reviews, news & interviews

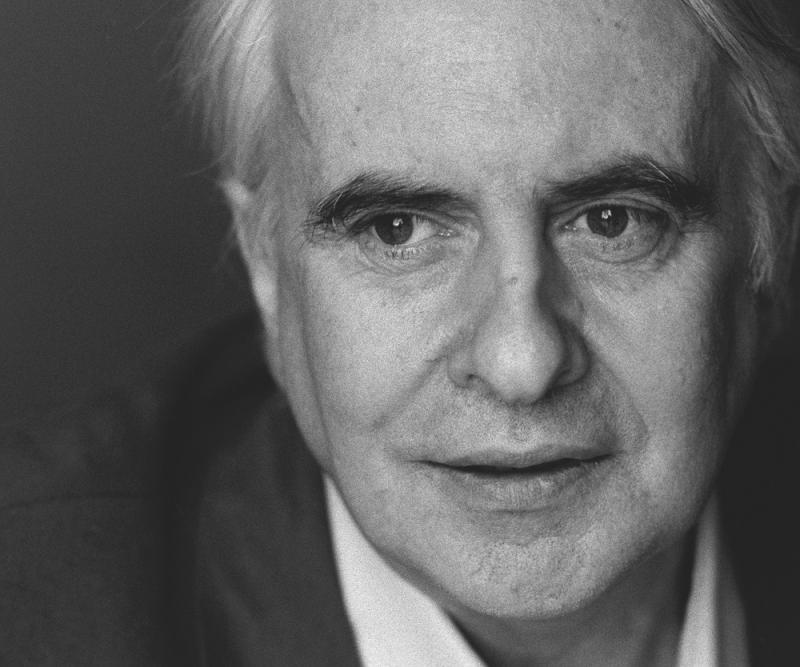

'Why we understand each other': Peter Gill on The York Realist

'Why we understand each other': Peter Gill on The York Realist

The playwright-director reflects on his 2001 play, revived at the Donmar and Sheffield Crucible

Fingers on buzzers… Question: What’s the connection between Days of Wine and Roses, Small Change, Making Noise Quietly and Versailles? Answer: They’re all past Donmar productions directed by Peter Gill.

But it’s not just his directing skill – no one in British theatre has a finer ear for the rhythm, pitch and placement of dialogue – that makes Gill a primary figure in the Donmar’s past and present. Not only did he direct the sons-and-mothers struggle Small Change and the post-Edwardian drama of family secrets and lies Versailles, he also wrote them. Robert Hastie’s revival of his 2001 play The York Realist makes Gill one of the most performed living dramatists in the Donmar’s 25-year history.

Anyone keen to appreciate the tenor of his writing should consider two facts. Firstly, among the almost 100 plays that Gill has directed in an impressively lengthy career (he was born in Cardiff in 1939 four days after the outbreak of World War Two), there’s his beautifully paced West End production of Speed-The-Plow. It’s a loud-mouthed, Hollywood-double-dealing drama by David Mamet and, in terms of tone and subject matter, couldn’t be farther apart from Gill’s own subtle shadings of emotional connections. Yet, as his perfectly calibrated production revealed, the two writers are strikingly similar in their understanding and handling of subtext. Both writers know language not only reveals, it also conceals. In their work, words often act as a mask since what characters talk about is often not what they’re really talking about.

That quality underpins the second important fact about Gill: that he has always been a Chekhov man. He recently wrote his second version of Uncle Vanya (this time for Theatre Clwyd); wrote a version of The Seagull for the RSC in 2000 starring Penelope Wilton and John Light; and, as founding director of the wildly influential Riverside Studios (which he ran from 1976-1980), he wrote and directed a now legendary adaptation of The Cherry Orchard with a cast including Judy Parfitt, Julie Covington, Stephen Rea and Eleanor Bron. On a wide-open stage with little furniture, Gill focused audiences on characters trying and, more often than not, failing to connect with one another.

Small wonder, therefore, that similar ideas arise in The York Realist. It takes place in a cottage on a remote farm in Yorkshire, coincidentally not unlike the setting of last year’s hit independent film God’s Own Country, another story of tension between two men from different backgrounds falling for one another. One of the most telling qualities of Gill’s play is its steady ring of truth. Exactly like the pivotal character, John (played by Jonathan Bailey, pictured below right in rehearsal with Ben Batt, photograph by Johan Persson), Gill was once a young trainee director who worked on a revival of York’s famous medieval Mystery Plays.

“My first job as an assistant director was working with Bill Gaskill on the York Mystery Plays. It was a very happy time. It was the mid-to-late Sixties and a huge experience for me because I had to organise everything. And I do mean everything since the cast were local people, a couple of whom, for example, were busy sheep-shearing at the time and I had to organise all the rehearsals. But," he adds quickly, “in all other respects it isn’t remotely autobiographical.” What spurred the play was not the recounting of an episode in his young life but two other entirely disconnected ideas. Gill had previously worked with the actor Marjorie Yates. A prevailing memory of a physical movement she made in a play conjured a character in Gill’s imagination. That character became Barbara in The York Realist. But the instigation for the play as a whole was much more about form. The play he wrote before, Certain Young Men, which premiered at the Almeida in 1999, was much more freewheeling: its setting non-naturalistic, its style fluid and poetic. “I thought my task should be to write something rather different from the plays that preceded it and a particular kind of play came into my mind: a one-set play.”

What spurred the play was not the recounting of an episode in his young life but two other entirely disconnected ideas. Gill had previously worked with the actor Marjorie Yates. A prevailing memory of a physical movement she made in a play conjured a character in Gill’s imagination. That character became Barbara in The York Realist. But the instigation for the play as a whole was much more about form. The play he wrote before, Certain Young Men, which premiered at the Almeida in 1999, was much more freewheeling: its setting non-naturalistic, its style fluid and poetic. “I thought my task should be to write something rather different from the plays that preceded it and a particular kind of play came into my mind: a one-set play.”

A play in which everything takes place in the same room was a form then, as now, deemed somewhat old-fashioned, the sort of play that had been abandoned in the Sixties and Seventies.

“Those plays were seen as being hermetic but, in retrospect, there was a contemplative element to them. It certainly was not ‘showbiz’, it was definitely not like going to a musical or even an epic play. It was a very specific kind of theatre. For years, if there wasn’t much money, you had to have two ‘names’ above the title and another name below. It was the only way to do a play commercially. That’s what you needed in order to get a good three-month run.” If that sounds antiquated, Gill’s considered use of the form to say something sharper, more radical, has plenty of precedent. “Remember, Osborne’s Look Back in Anger and Pinter’s The Birthday Party are one-set plays, the kind of plays their authors had been in when they were young men acting in repertory theatre.” (Pictured below: Lesley Nicol in rehearsal for The York Realist, photograph by Johan Persson)

Having not only directed some of Osborne’s and Pinter’s plays but having also come of age as a playwright beneath their shadows, Gill’s connections to their work has been personal. The same is true of his Donmar collaborations that stretch back to the Grandage years when he directed Owen McCafferty’s adaptation of Days of Wine and Roses.

Having not only directed some of Osborne’s and Pinter’s plays but having also come of age as a playwright beneath their shadows, Gill’s connections to their work has been personal. The same is true of his Donmar collaborations that stretch back to the Grandage years when he directed Owen McCafferty’s adaptation of Days of Wine and Roses.

“I’d known Michael when he was an actor – I offered him a job once. And then Josie Rourke was my assistant director not only on Luther at the National but also on the original production of The York Realist. I’ve also known Rob Hastie since he was an actor and have wanted to work with him for a long time.”

Given the setting and the way the characters are defined by the ties that bind, their location and class, it helps that Hastie is a Yorkshireman. Especially since, as he readily admits, Gill did no research.

“It just flowed. I don’t come from Yorkshire, but I’ve known a lot of Yorkshiremen. And I’m not remotely a country person.” He pauses for a moment, then sighs. “But when you get to a certain age, you know certain things. The specifics of a young man growing up in town in Cardiff and growing up in Yorkshire are different, but the things people tussle with at that point in their lives are the same. That’s why we understand each other or why certain plays move us.”

- The York Realist at the Donmar Warehouse until 24 March and Sheffield Crucible Theatre from 27 March until 7 April

© 2017 David Benedict

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Joyceana around Bloomsday, Dublin review - flawless adaptations of great dramatic writing

Chapters and scenes from 'Ulysses', 'Dubliners' and a children’s story vividly done

Joyceana around Bloomsday, Dublin review - flawless adaptations of great dramatic writing

Chapters and scenes from 'Ulysses', 'Dubliners' and a children’s story vividly done

Stereophonic, Duke of York's Theatre review - rich slice of creative life delivered by a 1970s rock band

David Adjmi's clever and compelling hit play gets a crack London cast

Stereophonic, Duke of York's Theatre review - rich slice of creative life delivered by a 1970s rock band

David Adjmi's clever and compelling hit play gets a crack London cast

North by Northwest, Alexandra Palace review - Hitchcock adaptation fails to fly

Emma Rice's storytelling at fault in misconceived production

North by Northwest, Alexandra Palace review - Hitchcock adaptation fails to fly

Emma Rice's storytelling at fault in misconceived production

Hamlet Hail to the Thief, RSC, Stratford review - Radiohead mark the Bard's card

An innovative take on a familiar play succeeds far more often than it fails

Hamlet Hail to the Thief, RSC, Stratford review - Radiohead mark the Bard's card

An innovative take on a familiar play succeeds far more often than it fails

The King of Pangea, King's Head Theatre review - grief and hope, but no connection

Heart and soul proves insufficient in world premiere of therapeutic show

The King of Pangea, King's Head Theatre review - grief and hope, but no connection

Heart and soul proves insufficient in world premiere of therapeutic show

A Midsummer Night's Dream, Bridge Theatre review - Nick Hytner's hit gender-bender returns refreshed

This Dream is a great night out, especially for Shakespeare first-timers

A Midsummer Night's Dream, Bridge Theatre review - Nick Hytner's hit gender-bender returns refreshed

This Dream is a great night out, especially for Shakespeare first-timers

Miss Myrtle’s Garden, Bush Theatre review - flowering talent, but needs weeding

New play about loss, love, grief and gardening is humane, but flawed

Miss Myrtle’s Garden, Bush Theatre review - flowering talent, but needs weeding

New play about loss, love, grief and gardening is humane, but flawed

Fiddler on the Roof, Barbican review - lean, muscular delivery ensures that every emotion rings true

This transfer from Regent's Park Open Air Theatre sustains its magic

Fiddler on the Roof, Barbican review - lean, muscular delivery ensures that every emotion rings true

This transfer from Regent's Park Open Air Theatre sustains its magic

In Praise of Love, Orange Tree Theatre review - subdued production of Rattigan's study of loving concealment

Unspoken emotion flows through this late work

In Praise of Love, Orange Tree Theatre review - subdued production of Rattigan's study of loving concealment

Unspoken emotion flows through this late work

Letters from Max, Hampstead Theatre review - inventively staged tale of two friends fighting loss with poetry

Sarah Ruhl turns her bond with a student into a lesson in how to love

Letters from Max, Hampstead Theatre review - inventively staged tale of two friends fighting loss with poetry

Sarah Ruhl turns her bond with a student into a lesson in how to love

Elephant, Menier Chocolate Factory review - subtle, humorous exploration of racial identity and music

Story of self-discovery through playing the piano resounds in Anoushka Lucas's solo show

Elephant, Menier Chocolate Factory review - subtle, humorous exploration of racial identity and music

Story of self-discovery through playing the piano resounds in Anoushka Lucas's solo show

This is My Family, Southwark Playhouse - London debut of 2013 Sheffield hit is feeling its age

Relatable or stereotyped - that's for you to decide

This is My Family, Southwark Playhouse - London debut of 2013 Sheffield hit is feeling its age

Relatable or stereotyped - that's for you to decide

Add comment