Arturo Ui, king of the Chicago cabbage trade, is Brecht’s Richard III. Egad, he even speaks in iambic pentameters, with a fair few nods at Shakespeare, though a certain cowlick and moustache locate him firmly at the centre of the 20th century nightmare. The problem for any actor, grateful though he may be for such a role, is that unlike Shakespeare’s Richard, Brecht’s Arturo starts out as an idiotic, malapropist thug, loathed by all: how to transform him credibly into a sleek, terrifying tyrant? For the director, the trick is to negotiate a haunting path between the over-insistent realism of the 1930s gangster setting from the perspective of 1941 and the timelessness of the myth.

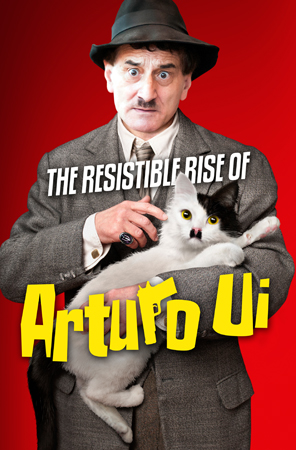

Henry Goodman, for all his comic skills, doesn’t have the answer to the first stumbling-block and Jonathan Church's production, first seen at the Chichester Festival Theatre in 2012, falters at the other hurdle. Goodman's Arturo is a bunchbacked, wambling caricature right at the start, and gets all the laughs – so how, you wonder, is he going to sustain the silly walks, the psychopathic explosions of rage, the half-a-Italiano accent, the brilliant wordstumbles? The comedy, it’s true, is cleverly modulated through to a classic scene in which an ac-tor (Keith Baxter, also hilarious) coaches our seemingly hopeless case in rhetoric, body language and voice production. The refrains of "and Brutus is an honourable man" in a lengthy travesty of Mark Antony’s speech mark the high point of hysteria in the production’s funny half: the only point at which the evening lives up to the promise of its irresistible publicity image (pictured below).

Unfortunately there comes a time when Brecht wants us to stop laughing and be very afraid. Mark Rylance managed exactly this kind of transition with his extraordinary Richard III, freezing our laughter in its tracks; Goodman's Arturo doesn't. He modulates his voice and learns to be suave in an especially unconvincing couple of scenes, the second again indebted to Richard III, with a truly honourable man's wife, then widow. She's played with striking visual hauteur but not quite enough voice by Lizzy McInnerny. Goodman’s blustering in the big final speech remains as unconvincing as Hitler’s performance in film footage. How did this ridiculous ham extend his empire? History doesn’t convince us, and nor does this interpretation.

Unfortunately there comes a time when Brecht wants us to stop laughing and be very afraid. Mark Rylance managed exactly this kind of transition with his extraordinary Richard III, freezing our laughter in its tracks; Goodman's Arturo doesn't. He modulates his voice and learns to be suave in an especially unconvincing couple of scenes, the second again indebted to Richard III, with a truly honourable man's wife, then widow. She's played with striking visual hauteur but not quite enough voice by Lizzy McInnerny. Goodman’s blustering in the big final speech remains as unconvincing as Hitler’s performance in film footage. How did this ridiculous ham extend his empire? History doesn’t convince us, and nor does this interpretation.

Part of Brecht’s point is that the times, the dismal circumstances of financial collapse and a morally weak democratic opposition, smooth the path for what should have been a resistible rise. So we have to be gripped by the world around the monster. That happens very fitfully in Church’s production. It begins promisingly with stylish '30s music and Colin Stinton’s witty introduction of the main roles in the play-within-a-play. Then it slumps completely as a group of actors trying hard with the accents make us nod with their odd, uneasy delivery of the Shakespearean blank verse. Not an easy task, it’s true, and one that fails completely at this crucial set-up point. A couple of cross-gender women in a villainous role or two, as in the far more imaginative Edward II at the National, might not have gone amiss in this male-dominated world.

There are good performances from William Gaunt as silver-haired Dogsborough, the patriarch Hindenburg of Chicago, and David Sturzaker as the Göring figure Givola, as well as a bad one – no surprise here – from Michael Feast, struggling to be the toughest of the gangsters Ernesto Roma (a parody of doomed SA commander Röhm). Simon Higlett’s sets prove malleable within a small space, but seem far too traditional for Brecht’s often surreal objective, while Matthew Scott’s score is weakest when it most needs to conjure menace, verging on the style of The Weakest Link or even – if anyone remembers it – Blake’s Seven. The comic moments work and it's always a pleasure to listen to George Tabori's translation as revised by Alistair Beaton, but – pace Goodman’s neatly delivered little envoi once he’s removed the moustache – there's no horror in the heart of this farce.

- The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui at the Duchess Theatre until 7 December

- Read David Nice's blog, I'll Think of Something Later

Add comment