50 years of Kind Of Blue | reviews, news & interviews

50 years of Kind Of Blue

50 years of Kind Of Blue

Miles Davis classic in concert

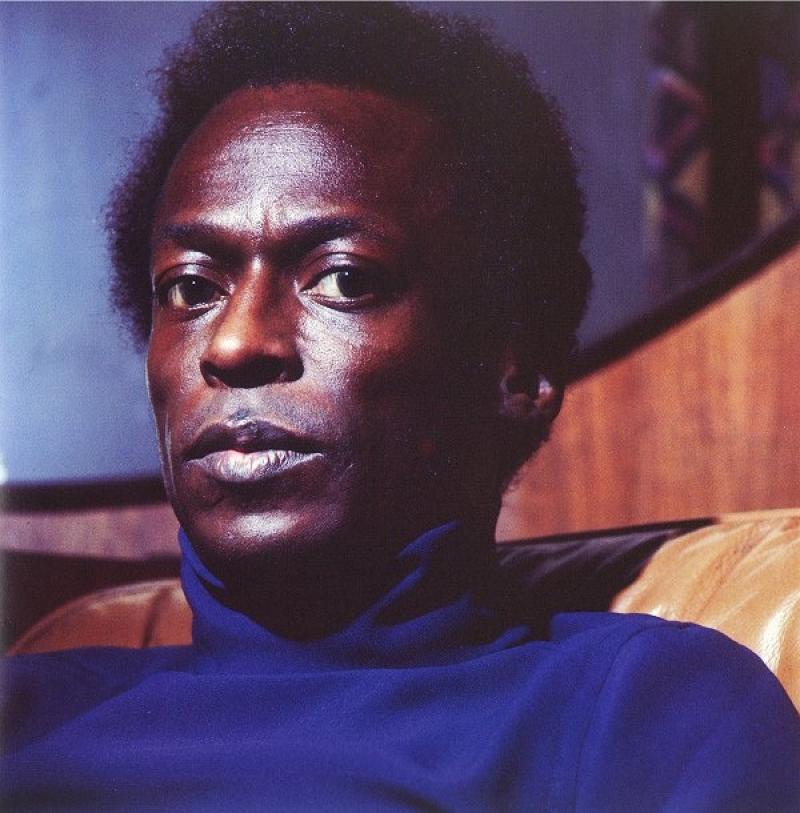

When Miles Davis led his band into a deconsecrated church in New York in August 1959 to record the album that became Kind of Blue, drummer James Cobb recalled that “it was just another date for us. ” How wrong he was. A little over 50 years later, Cobb - the sole survivor of the original sessions – brought his So What band to London on Thursday to celebrate what many now regard as the most important and popular jazz record ever made.

Thursday's concert at London’s Tower Festival marked another event in an anniversary that has been greeted with the sort of delirious fanfare normally reserved for pop classics such as Sgt Pepper, Brian Wilson’s Smile or Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks. To remind us all of its seminal influence, the renowned British jazz writer Richard Williams recently published a book, The Blue Moment, citing the myriad ways in which Kind Of Blue affected modern music – from rock to contemporary classical and ambient electronica – in the decades that followed its release. The Velvet Underground, Terry Reilly and the Sufi singer Pandit Pran Nath are just three of the figures held to have taken cues from Davis’s cool, atmospheres and declamatory horn arrangements. Even Brian Eno – no jazz muso himself – is reckoned to have given Kind Of Blue a close listen.

There are more obvious reasons however why this record has lasted so well, sold millions and become a staple in the collections of listeners who don’t necessarily consider themselves jazz aficionados. For one thing, it contains some of Davis’s most memorable and sinuous melodies – the so-called “head arrangements” which introduce the unhurried saxophone improvisations of John Coltrane and Cannonball Adderley, and the sublime pianistic inventions of Bill Evans.

As an instrumentalist, Miles himself seems to have been in an unusually generous mood. The master of the melancholy trumpet had built a steely reputation throughout the 1950s for his stylistic opposition to the excitements of "hot jazz" and the showy technical flourishes of be-bop. Literally turning his back on the audience at times, Davis had become an emissary of arty jazz modernism and alienated many of the genre’s old constituency in the process. His bruised, soulful tone was impeccable, but not to the taste of those brought up on the wiild tootling of, say, Dizzie Gillespie. The late Philip Larkin, sometime jazz critic of the Daily Telegraph, famously inveighed against “the slow creep” of Davis’s trumpet solos.

It wasn’t just the trad-loving Larkin crew who were getting restless. By 1959, jazz could no longer claim to be the automatic first choice of the young bo-ho set who had claimed it as the soundtrack for their underground enthusiasms. Coming from different directions and demographics, rock and roll and the folk revival were both making major inroads into a more diversified pop scene. Jazz was getting undeniably older and, 50 years after it burst out of the clubs of New Orleans, was starting to feel rather like the classical music of the 20th century.

Part of the genius of Kind Of Blue lay in its clear-eyed recognition that this was the case, and that popular music now owed it to its audience to express adult emotions rather than sultry, sulky poses and dance tunes. Davis never got that balance better. As his career rolled on through the Sixtes and Seventies he found himself pulled youthfully in the direction of rock and funk, on the one hand, and the more experimental urgings of the "progressive" movement on the other. He made some very interesting albums – In A Silent Way and Bitches Brew being two – but compared to the blissful ebb and flow of Kind Of Blue, they had an air of contrivance and were hard to love.

In 1959, Miles Davis was his own man, occupying a unique space in a popular musical landscape on the cusp of unimaginable upheaval. Soon afterwards he got caught up in that upheaval and ultimately lost his way. He became an icon, a drug addict, a celebrity, an enigma. Last Thursday night’s show at Tower Festival offered a chance to remember Miles at his most human, inspired and relaxed; before the pressure came down on his gentle and delicately refined kind of blue.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Macbeth, RSC, Stratford review - Glaswegian gangs and ghoulies prove gripping

Sam Heughan's Macbeth cannot quite find a home in a mobster pub

Macbeth, RSC, Stratford review - Glaswegian gangs and ghoulies prove gripping

Sam Heughan's Macbeth cannot quite find a home in a mobster pub

Mr Scorsese, Apple TV review - perfectly pitched documentary series with fascinating insights

Rebecca Miller musters a stellar roster of articulate talking heads for this thorough portrait

Mr Scorsese, Apple TV review - perfectly pitched documentary series with fascinating insights

Rebecca Miller musters a stellar roster of articulate talking heads for this thorough portrait

Madama Butterfly, Irish National Opera review - visual and vocal wings, earthbound soul

Celine Byrne sings gorgeously but doesn’t round out a great operatic character study

Madama Butterfly, Irish National Opera review - visual and vocal wings, earthbound soul

Celine Byrne sings gorgeously but doesn’t round out a great operatic character study

Hallé John Adams festival, Bridgewater Hall / RNCM, Manchester review - standing ovations for today's music

From 1980 to 2025 with the West Coast’s pied piper and his eager following

Hallé John Adams festival, Bridgewater Hall / RNCM, Manchester review - standing ovations for today's music

From 1980 to 2025 with the West Coast’s pied piper and his eager following

'Vicious Delicious' is a tasty, burlesque-rockin' debut from pop hellion Luvcat

Contagious yarns of lust and nightlife adventure from new pop minx

'Vicious Delicious' is a tasty, burlesque-rockin' debut from pop hellion Luvcat

Contagious yarns of lust and nightlife adventure from new pop minx

theartsdesk at Wexford Festival Opera 2025 - two strong productions, mostly fine casting, and a star is born

Four operas and an outstanding lunchtime recital in two days

theartsdesk at Wexford Festival Opera 2025 - two strong productions, mostly fine casting, and a star is born

Four operas and an outstanding lunchtime recital in two days

Kaploukhii, Greenwich Chamber Orchestra, Cutts, St James's Piccadilly review - promising young pianist

A robust and assertive Beethoven concerto suggests a player to follow

Kaploukhii, Greenwich Chamber Orchestra, Cutts, St James's Piccadilly review - promising young pianist

A robust and assertive Beethoven concerto suggests a player to follow

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

The Line of Beauty, Almeida Theatre review - the 80s revisited in theatrically ravishing form

Alan Hollinghurst novel is cunningly filleted, very finely acted

The Line of Beauty, Almeida Theatre review - the 80s revisited in theatrically ravishing form

Alan Hollinghurst novel is cunningly filleted, very finely acted

Add comment