London Film Festival 2023 - Scorsese on Scorsese | reviews, news & interviews

London Film Festival 2023 - Scorsese on Scorsese

London Film Festival 2023 - Scorsese on Scorsese

The master looks back from 'Mean Streets' to 'Flower Moon', live in London

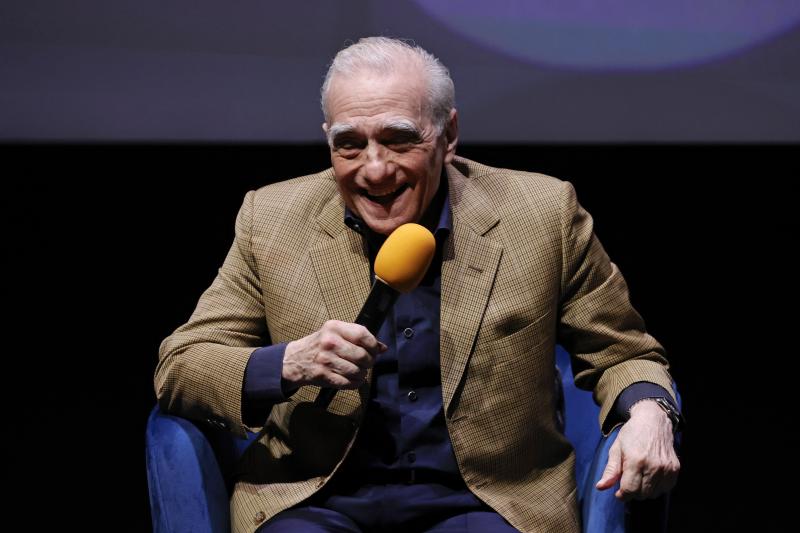

Martin Scorsese walks onstage to a hero’s welcome, shoulders a little hunched, with a touch of sideways shuffle or hustle, taking acclaim in his stride at 80. He has sold out London’s 2,700-capacity Royal Festival Hall for the BFI’s biggest Screen Talk by far, and the queue for returns stretches into the street, to see a director as big as any star.

Fellow director Edgar Wright is here to interview him for 60 minutes about his 27-film career, but barely gets beyond 1980’s Raging Bull in 90. The coked-up motormouth familiar in Scorsese cameos from his backseat rant at Travis Bickle to his parodic speed-rap with slow-burning, deliberate jazzman Dexter Gordon in Round Midnight, that vocal precursor to his inheritor Tarantino’s pumped-up pulp cineaste riffs, is dialled down. “I had a feeling of pride by inspiring other people,” he says of steering younger directors to classic cinema. “I always thought of myself more as a teacher than a filmmaker.” Maybe it’s in this educative spirit, maybe octogenarian mellowing, but Scorsese is slow and clear, his accent and nervy rhythmic hitches still Lower East Side. Hitting his stride, he talks in hypnotically soft, even, short phrases, punching line-ends. His professed admiration for stand-up fuelled The King of Comedy, and he pauses yarns, palms up, in stand-up moves.

Wright sticks closely to the fanboy mainstream for clips – Mean Streets, Taxi Driver, The Wolf of Wall Street – but Scorsese responds deeply to this well-worn terrain, finding rich anecdote and philosophy in his past. There’s barely time to mention his fine new epic of American genocide and venality, Killers of the Flower Moon, Silence’s intensely felt and reasoned, blood-flecked meditation on faith, or his monumental, febrile capstone to his own Mob films, The Irishman, pictured below: a masterful late period.

Wright instead wisely ask how Scorsese got to Mean Streets. Suddenly, it’s 1945, and asthma has exiled the boy Marty from the streets outside. Church and cinema became his “safe spaces”, the latter a 13-cent portal with “wooden seats, gum on the floor”, offering cultural wonder and taste. “Shane, I was 12 years old, we knew that was special.” Sirk’s Magnificent Obsession, Lang’s The Big Heat, Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard – “kind of a horror film” –and Italian neo-realist films on late ‘40s local TV – “They were speaking the same language as my grandparents. I saw them reacting, and we were them” – all fed him. “I had a sense of other cultures coming in,” he says. The American experimental underground of Stan Brakhage and Shirley Clarke made friends “angry – I just tried to go with it”. This early, he was “open to all ways of telling stories in pictures.” He makes wind-up motions at his answer to one question. “It was,” he apologises, “a long trip…”

Wright instead wisely ask how Scorsese got to Mean Streets. Suddenly, it’s 1945, and asthma has exiled the boy Marty from the streets outside. Church and cinema became his “safe spaces”, the latter a 13-cent portal with “wooden seats, gum on the floor”, offering cultural wonder and taste. “Shane, I was 12 years old, we knew that was special.” Sirk’s Magnificent Obsession, Lang’s The Big Heat, Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard – “kind of a horror film” –and Italian neo-realist films on late ‘40s local TV – “They were speaking the same language as my grandparents. I saw them reacting, and we were them” – all fed him. “I had a sense of other cultures coming in,” he says. The American experimental underground of Stan Brakhage and Shirley Clarke made friends “angry – I just tried to go with it”. This early, he was “open to all ways of telling stories in pictures.” He makes wind-up motions at his answer to one question. “It was,” he apologises, “a long trip…”

Young Marty began making proto-storyboards for a putative ancient Roman epic – “In my mind, the pictures moved” – in secret from his neighbours. “You gotta understand,” he councils, “this was a tenement apartment on the Lower East Side. I don’t know if it was working-class. But a lot of it was street stuff – a pretty rough place.” New York University drew him from this cloistered home. “I was quite young and I guess you would call it provincial…I came crashing up against the outside world.” The New York Film Festival was a further education, he tells this rapt London Film Festival crowd, as his apprenticeship moved through the Sixties. “When I saw Bertolucci’s Before the Revolution, I wanted that. I wanted to express myself that way.” His feature debut, Who’s That Knocking At My Door (1967), “very personal” in depicting Little Italy, “where you couldn’t really bring cameras, or name certain people”, tried to match this ambition “straight away…and I blew it” (Harvey Keitel and Zina Bethune pictured in Who's That Knocking At My Door below).

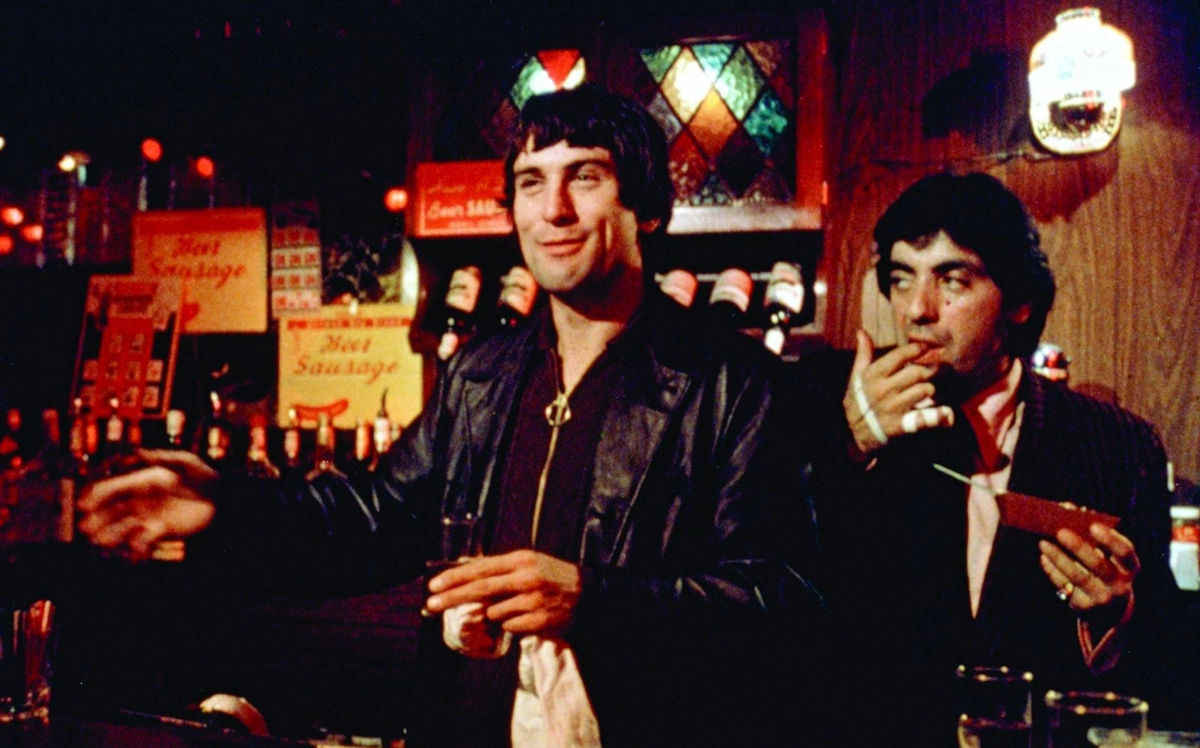

From 1966 to 1972, Scorsese worked, moving to California and learning filmmaking’s practical art from Roger Corman and others till, provoked by Cassavetes, his third feature Mean Streets roared onto the screen speaking his own language of rock’n’roll and street-level Mob patois, frenetic even in his slow-motion glide following Johnny Boy down the bar, two college girls on his arm, to the Stones’ swaggering, maleficent “Jumping Jack Flash”. “Well, they’re wonderful, the two of them,” Scorsese says fondly, watching De Niro and Harvey Keitel in that scene. He notes a “playfulness” to the words, echoing Abbott and Costello, Crosby and Hope. De Niro suggested the scene, writing and improvising his lines.

From 1966 to 1972, Scorsese worked, moving to California and learning filmmaking’s practical art from Roger Corman and others till, provoked by Cassavetes, his third feature Mean Streets roared onto the screen speaking his own language of rock’n’roll and street-level Mob patois, frenetic even in his slow-motion glide following Johnny Boy down the bar, two college girls on his arm, to the Stones’ swaggering, maleficent “Jumping Jack Flash”. “Well, they’re wonderful, the two of them,” Scorsese says fondly, watching De Niro and Harvey Keitel in that scene. He notes a “playfulness” to the words, echoing Abbott and Costello, Crosby and Hope. De Niro suggested the scene, writing and improvising his lines.

Bobby the Greenwich Village artist’s son had crossed the tracks early, first running into Marty aged 16, and haunting Little Italy’s “restricted members club” the Alto Knights. Both men knew the reality behind Mean Streets’ steamy shadows, neon and bloody palette. “The character Johnny Boy is based on is still alive,” Scorsese says. “De Niro knew the people I made the film about – Joey Clams is a real name, Joey Scala is not…” (De Niro pictured with David Proval below)

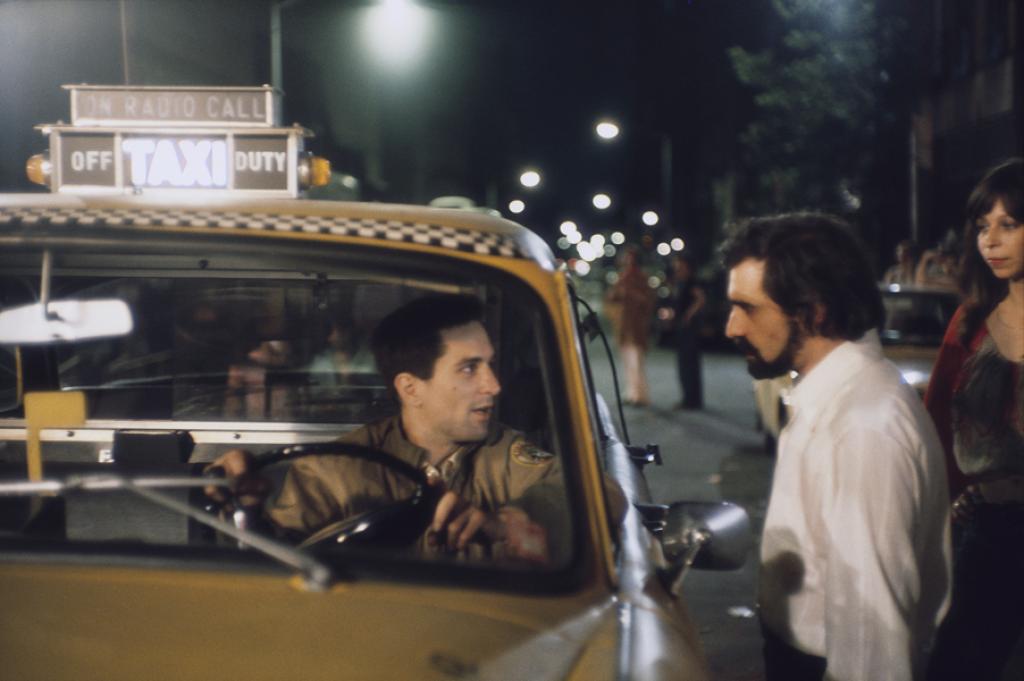

Taxi Driver, in turn a personal film for its writer Paul Schrader and star De Niro, provokes a reverie on Scorsese’s identification with Travis Bickle. “They were all-consuming, I should say,” he reflects on his time making this “coming of age” film about “my own anger and my own frustration”. “I couldn’t defend myself on the street from a world where arguments were often won by force,” he says. “Here, [Bickle’s] a frustrated man. He has a passion…we had the passion for this.” Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground was his way in. “I really connected with the Underground Man. I felt I was him. And I was looking for a way out.” The novel’s anti-hero is “rewarded for crossing the line”, offering “an ambiguous way of celebrating the violent”. Taxi Driver’s climactic blood-frenzy meanwhile demanded a censor-calming, muted colour-scheme taken from John Huston’s Moby Dick, making “the blood…less distracting”, and the film “what I always wanted it to be…a Weegee photograph on the cover of a tabloid”. Weegee haunted the post-war Lower East Side, unflinchingly snapping its gruesome nocturnal crimes. One of Scorsese’s friends, he says, ended up dead on such a tabloid cover.

Taxi Driver, in turn a personal film for its writer Paul Schrader and star De Niro, provokes a reverie on Scorsese’s identification with Travis Bickle. “They were all-consuming, I should say,” he reflects on his time making this “coming of age” film about “my own anger and my own frustration”. “I couldn’t defend myself on the street from a world where arguments were often won by force,” he says. “Here, [Bickle’s] a frustrated man. He has a passion…we had the passion for this.” Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground was his way in. “I really connected with the Underground Man. I felt I was him. And I was looking for a way out.” The novel’s anti-hero is “rewarded for crossing the line”, offering “an ambiguous way of celebrating the violent”. Taxi Driver’s climactic blood-frenzy meanwhile demanded a censor-calming, muted colour-scheme taken from John Huston’s Moby Dick, making “the blood…less distracting”, and the film “what I always wanted it to be…a Weegee photograph on the cover of a tabloid”. Weegee haunted the post-war Lower East Side, unflinchingly snapping its gruesome nocturnal crimes. One of Scorsese’s friends, he says, ended up dead on such a tabloid cover.

Taxi Driver’s success was followed by 1977’s big-budget flop New York, New York, and Hollywood asked Scorsese to leave. “Not just for the filmmaking…” he ruefully laughs of weeks coked-up with his The Last Waltz pal Robbie Robertson in rooms blacking out LA’s alien, endless sun. He was in the wilderness till Raging Bull, wondering: “Where am I gonna go?” “Depressed”, Scorsese “might have been lost forever”. “When you’re down and out, you get kicked,” he says, remembering with soft reflection.

Taxi Driver’s success was followed by 1977’s big-budget flop New York, New York, and Hollywood asked Scorsese to leave. “Not just for the filmmaking…” he ruefully laughs of weeks coked-up with his The Last Waltz pal Robbie Robertson in rooms blacking out LA’s alien, endless sun. He was in the wilderness till Raging Bull, wondering: “Where am I gonna go?” “Depressed”, Scorsese “might have been lost forever”. “When you’re down and out, you get kicked,” he says, remembering with soft reflection.

Wright cues a The King of Comedy clip, another misunderstood, rejected film, in which De Niro’s failed, envious stand-up Rupert Pupkin kidnaps his chat-show host idol, played by Jerry Lewis, in a chilly satire of maddened celebrity. “How much of me is Rupert, how much of me is Jerry?” Scorsese muses, uncomfortable. “A little too close to home.” His creative comeback after a scuffling Eighties, Goodfellas (1990), was inspired by stand-up too: “riffing on tangents, then reel it in”. The result was visceral, addictive, Henry Hill’s coke binge transfused into film: “not consuming a movie, being overwhelmed by it”.

Decades speed by as time ticks down. The Departed was influenced by “pushing narrative as far as you could” in Scorsese’s music doc George Harrison: Living in the Material World; Gangs of New York shares Killers of the Flower Moon’s sense of time. He alights on Howard Hughes biopic The Aviator (2004), finding connection in Hughes’ obsessive-compulsiveness and his own fear of flight, Hughes’ milieu. DiCaprio, pictured below, in his second of six Scorsese films, grew up in a scene of naked meltdown. “Oh,” Scorsese sighs, deflated, when a The Wolf of Wall Street clip represents the Di Caprio years. Killers of the Flower Moon’s sober yet propulsive saga, with DiCaprio at his sleazy, queasy zenith as weak, venal family to De Niro’s smiling Indian-killer, depicts “the insidious nature of complicity…next thing you know, [it’s] genocidal”.

There is time for the future. Scorsese can seem Canute-like in his bafflement at franchise films’ devouring of cinema, the unintended consequence of his Movie Brat peers Lucas and Spielberg. Today, his words complete a circle with the kid “open to all ways of telling stories in pictures”.

There is time for the future. Scorsese can seem Canute-like in his bafflement at franchise films’ devouring of cinema, the unintended consequence of his Movie Brat peers Lucas and Spielberg. Today, his words complete a circle with the kid “open to all ways of telling stories in pictures”.

“What does a shot mean now?” he asks. “Should it be the way it’s been for the last 90, 100 years?” – made for cinema, not a fragmenting phone. “I do [think so], but I’m old.” The answer, he accepts without qualm, is “over to you”.

“You gotta go past technology,” he said earlier of Taxi Driver. “You try something crazy.” “New technology” may now enhance “serious film”, but “big audiences watching on a big screen” will, he predicts, be tough in the looming future. That future is now even for Scorsese, of course, as major directors’ major films, The Irishman included, barely reach big screens, routinely dissolving in streaming’s cold algorithmic calculus.

“If you want to have an experience that changes your life,” all-consuming cinema’s avatar concludes, “it can’t be thought of as content.” After another, grateful standing ovation, Marty goes back to work.

- 'Killers of the Flower Moon' is in UK cinemas from October 20

- Read more film reviews and features on theartsdesk

Share this article

Add comment

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Love Lies Bleeding review - a pumped-up neo-noir

There's darkness on the edge of town in Rose Glass's sweaty, violent New Queer gem

Love Lies Bleeding review - a pumped-up neo-noir

There's darkness on the edge of town in Rose Glass's sweaty, violent New Queer gem

Nezouh review - seeking magic in a war

A movie that looks on the dreamier side of Syrian strife

Nezouh review - seeking magic in a war

A movie that looks on the dreamier side of Syrian strife

Blu-ray: The Dreamers

Bertolucci revisits May '68 via intoxicated, transgressive sex, lit up by the debuting Eva Green

Blu-ray: The Dreamers

Bertolucci revisits May '68 via intoxicated, transgressive sex, lit up by the debuting Eva Green

theartsdesk Q&A: Marco Bellocchio - the last maestro

Italian cinema's vigorous grand old man discusses Kidnapped, conversion, anarchy and faith in cinema

theartsdesk Q&A: Marco Bellocchio - the last maestro

Italian cinema's vigorous grand old man discusses Kidnapped, conversion, anarchy and faith in cinema

I.S.S. review - sci-fi with a sting in the tail

The imperilled space station isn't the worst place to be

I.S.S. review - sci-fi with a sting in the tail

The imperilled space station isn't the worst place to be

That They May Face The Rising Sun review - lyrical adaptation of John McGahern's novel

Pat Collins extracts the magic of country life in the west of Ireland in his third feature film

That They May Face The Rising Sun review - lyrical adaptation of John McGahern's novel

Pat Collins extracts the magic of country life in the west of Ireland in his third feature film

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

DVD/Blu-Ray: Priscilla

The disc extras smartly contextualise Sofia Coppola's eighth feature

DVD/Blu-Ray: Priscilla

The disc extras smartly contextualise Sofia Coppola's eighth feature

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

All You Need Is Death review - a future folk horror classic

Irish folkies seek a cursed ancient song in Paul Duane's impressive fiction debut

All You Need Is Death review - a future folk horror classic

Irish folkies seek a cursed ancient song in Paul Duane's impressive fiction debut

If Only I Could Hibernate review - kids in grinding poverty in Ulaanbaatar

Mongolian director Zoljargal Purevdash's compelling debut

If Only I Could Hibernate review - kids in grinding poverty in Ulaanbaatar

Mongolian director Zoljargal Purevdash's compelling debut

The Book of Clarence review - larky jaunt through biblical epic territory

LaKeith Stanfield is impressively watchable as the Messiah's near-neighbour

The Book of Clarence review - larky jaunt through biblical epic territory

LaKeith Stanfield is impressively watchable as the Messiah's near-neighbour

Comments

Great account Nick, thank you

Great account Nick, thank you for writing it up!