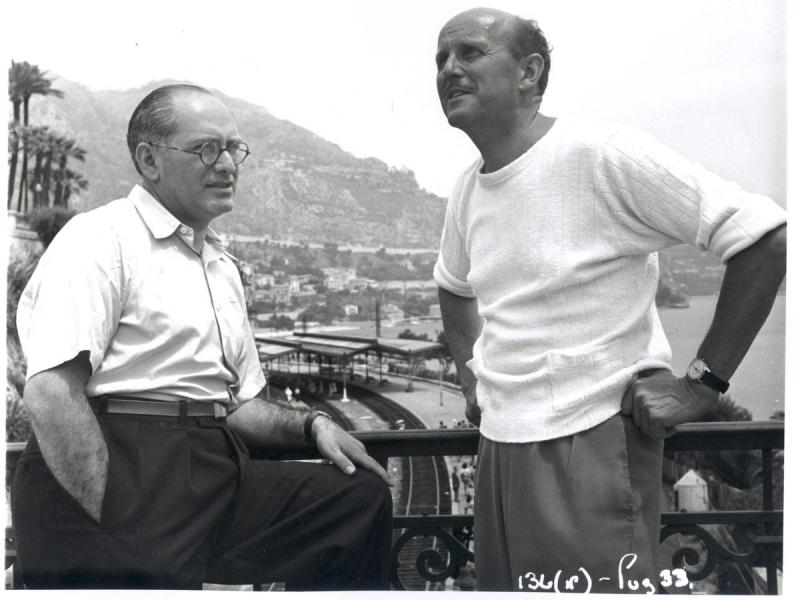

'Glorious, isn't it?' Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's Subversive Cinema | reviews, news & interviews

'Glorious, isn't it?' Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's Subversive Cinema

'Glorious, isn't it?' Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's Subversive Cinema

theartsdesk opens a series timed to the BFI's Powell and Pressburger season

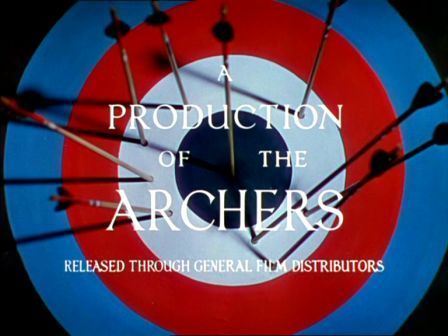

Announcing “A Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger production” or, alternatively “A Production of the Archers”, an arrow thuds into the centre of a roundel. Whether in black and white or colour, that famous rubric not only conflates the auras of Robin Hood and the Royal Air Force, but issues a warning you’re about to get a shot in the eye.

The critic Ian Christie, one of Powell and Pressburger’s earliest champions, wrote in “Arrows of Desire” (1985), his second book on the great writer-director-producer duo, that the logo (pictured below) was “a promise of ‘real film magic’ for forties and fifties audiences on both of sides of the Atlantic”.

In these days of multiple screening platforms, it’s a promise for all points beyond Britain and North America, too, geographically and temporally, as suggested by the title of the BFI's mammoth nationwide retrospective “Cinema Unbound: The Creative Worlds of Powell and Pressburger” (running through 31 December).

In these days of multiple screening platforms, it’s a promise for all points beyond Britain and North America, too, geographically and temporally, as suggested by the title of the BFI's mammoth nationwide retrospective “Cinema Unbound: The Creative Worlds of Powell and Pressburger” (running through 31 December).

For all their Britishness and Empire-consciousness, requisite during World War II, the Archers’ perspective was internationalist and defied the parameters of the here and now. But that internationalism is a source of uneasiness, as was the Archers’ dazzling European visual aesthetic and unbridled Romanticism – qualities deemed most improper by critics who expected their national cinema to tow the lines of conventional naturalism and dingy realism.

What madness, after all, was it that sanctioned Powell and Pressburger to unleash a repressed nocturnal predator (Eric Portman) armed with glue on young women fearful for their hair during the blackout in A Canterbury Tale (1944) – and then persuade us that he’s a village magus and instrument of a benign God? What permitted the Archers the seminal meta moment in A Matter of Life and Death (1946) when a French aristocrat (Marius Goring, pictured below), guillotined about 1792 but on a mission from monochromatic Heaven to the rainbow-hued English coast around 1944, laments “One is starved for Technicolor up there!”

In the six consecutive masterpieces Powell made between 1943 and 1948 – a run equalled only by Josef von Sternberg and Jean Renoir (perhaps) in the 1930s and Alfred Hitchcock between 1958 and 1964 – time is the leveller that reveals nothing much changes, in individual psyches, in national identities, in the incessant rhythms of daily life that create culture, and in the rituals and stories that create myths, no matter how many boundaries are broken and borders crossed.

Thus, in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), the same idealised woman (Deborah Kerr) materialises in three different guises over 40 years in the life of a British soldier (Roger Livesey), who having fallen into the swimming pool in his gentleman’s club as a crusty Home Guard officer, relives his experiences forwards from when he was a dashing young officer in 1902.

Thus, in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), the same idealised woman (Deborah Kerr) materialises in three different guises over 40 years in the life of a British soldier (Roger Livesey), who having fallen into the swimming pool in his gentleman’s club as a crusty Home Guard officer, relives his experiences forwards from when he was a dashing young officer in 1902.

In A Canterbury Tale, a medieval falconer morphs into A World War II infantryman, his falcon into a Spitfire (which showed Stanley Kubrick how to collapse millennia at the start of 2001: A Space Odyssey), and a trio of depressed modern-day pilgrims (Dennis Price, Sheila Sim, Sgt John Sweet) – retracing the steps of Chaucer's – receive unexpected blessings.

Virtually all of Powell and Pressburger’s films feature exiles, including external exiles, forced to confront existential realities far from home. They include Anton Walbrook’s German POW – a kind of self-portrait by the Jewish Hungarian émigré Pressburger – in Blimp and a materialistic Englishwoman (Wendy Hiller) confounded by Celtic mysticism (and Livesey’s impoverished but virile laird) in I Know Where I’m Going! (1945). There is the brain-damaged RAF bomber pilot and poet (David Niven) fighting for survival in a heavenly court in A Matter of Life and Death and the demure British nun (Deborah Kerr) and her equally sex-starved colleague (Kathleen Byron, pictured below) in the Himalayas in Black Narcissus (1947).

And there is the English ballerina (Moira Shearer) torn apart by the conflicting demands of love and art on the Cote d’Azur in The Red Shoes (1948), Walbrook’s autocratic impresario in that film a kind of self-portrait by Powell. Autobiography penetrates these films – not least Peeping Tom (1960), a visionary study of cine-sadism and voyeurism, made by Powell without Pressburger, and the film maudit that effectively cancelled its director’s career when he was just 54.

Over the next two months, theartsdesk will publish a series of essays and other articles saluting the Archers' subversive movies, which by the time of the experimental dance music extravaganza The Tales of Hoffmann (1951) were pushing at the limits of what cinema was and could be, toward synaesthesia and controlled delirium.

Over the next two months, theartsdesk will publish a series of essays and other articles saluting the Archers' subversive movies, which by the time of the experimental dance music extravaganza The Tales of Hoffmann (1951) were pushing at the limits of what cinema was and could be, toward synaesthesia and controlled delirium.

We will begin with an essay by Helen Hawkins on how Powell and Pressburger presented their women characters in the fraught years of the 1940s – a subject not without fraughtness itself.

Explore topics

Share this article

more Film

I.S.S. review - sci-fi with a sting in the tail

The imperilled space station isn't the worst place to be

I.S.S. review - sci-fi with a sting in the tail

The imperilled space station isn't the worst place to be

That They May Face The Rising Sun review - lyrical adaptation of John McGahern's novel

Pat Collins extracts the magic of country life in the west of Ireland in his third feature film

That They May Face The Rising Sun review - lyrical adaptation of John McGahern's novel

Pat Collins extracts the magic of country life in the west of Ireland in his third feature film

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

DVD/Blu-Ray: Priscilla

The disc extras smartly contextualise Sofia Coppola's eighth feature

DVD/Blu-Ray: Priscilla

The disc extras smartly contextualise Sofia Coppola's eighth feature

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

All You Need Is Death review - a future folk horror classic

Irish folkies seek a cursed ancient song in Paul Duane's impressive fiction debut

All You Need Is Death review - a future folk horror classic

Irish folkies seek a cursed ancient song in Paul Duane's impressive fiction debut

If Only I Could Hibernate review - kids in grinding poverty in Ulaanbaatar

Mongolian director Zoljargal Purevdash's compelling debut

If Only I Could Hibernate review - kids in grinding poverty in Ulaanbaatar

Mongolian director Zoljargal Purevdash's compelling debut

The Book of Clarence review - larky jaunt through biblical epic territory

LaKeith Stanfield is impressively watchable as the Messiah's near-neighbour

The Book of Clarence review - larky jaunt through biblical epic territory

LaKeith Stanfield is impressively watchable as the Messiah's near-neighbour

Back to Black review - rock biopic with a loving but soft touch

Marisa Abela evokes the genius of Amy Winehouse, with a few warts minimised

Back to Black review - rock biopic with a loving but soft touch

Marisa Abela evokes the genius of Amy Winehouse, with a few warts minimised

Civil War review - God help America

A horrifying State of the Union address from Alex Garland

Civil War review - God help America

A horrifying State of the Union address from Alex Garland

The Teachers' Lounge - teacher-pupil relationships under the microscope

Thoughtful, painful meditation on status, crime, and power

The Teachers' Lounge - teacher-pupil relationships under the microscope

Thoughtful, painful meditation on status, crime, and power

Blu-ray: Happy End (Šťastný konec)

Technically brilliant black comedy hasn't aged well

Blu-ray: Happy End (Šťastný konec)

Technically brilliant black comedy hasn't aged well

Add comment