DVD: De Palma | reviews, news & interviews

DVD: De Palma

DVD: De Palma

We take a long look at the lurid, brilliant Movie Brat

When Carrie White’s hand jumps out of the grave to drag Amy Irving’s character to hell, the shock is Psycho-intense.

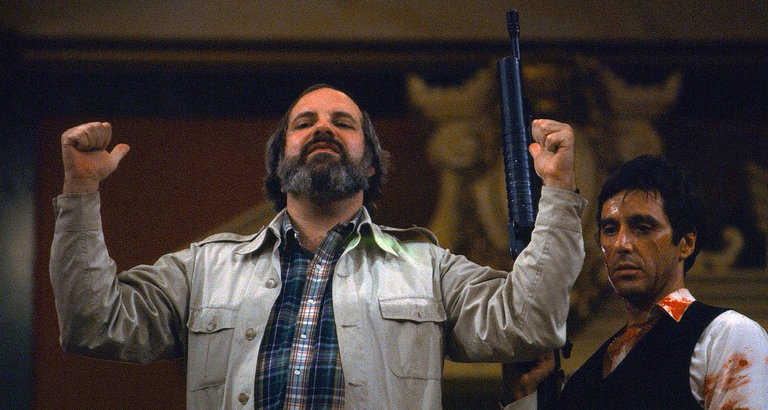

Among the Movie Brats who marvellously came of age in the Seventies, and are now mostly in their seventies – Coppola, Spielberg, Scorsese, Lucas – De Palma, pictured below filming Scarface, is still the sensational, lurid outsider. His few big hits in a prolific career – Carrie (1976), Dressed to Kill (1980), The Untouchables (1987), Mission: Impossible (1996) – were unstable one-offs, interspersed with wild darts towards the seedy (Body Double) and wacky (Wise Guys), or failed grasps for profundity and respect (Casualties of War, The Bonfire of the Vanities, Redacted). It has been a chaotic, Jeckyll-and-Hyde professional journey. But De Palma’s enraptured relationship with the camera has remained faithful.

Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow’s documentary, De Palma, begins with that affair’s primal scene, Hitchcock’s Vertigo, watched by 18-year-old Brian on its 1958 release. He remembers it as both magically transfixing and hermetically cinematic: a film about the director’s spell, and the violent impulses that can contain, as James Stewart and Kim Novak’s characters are devastated by Hitchcock.

Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow’s documentary, De Palma, begins with that affair’s primal scene, Hitchcock’s Vertigo, watched by 18-year-old Brian on its 1958 release. He remembers it as both magically transfixing and hermetically cinematic: a film about the director’s spell, and the violent impulses that can contain, as James Stewart and Kim Novak’s characters are devastated by Hitchcock.

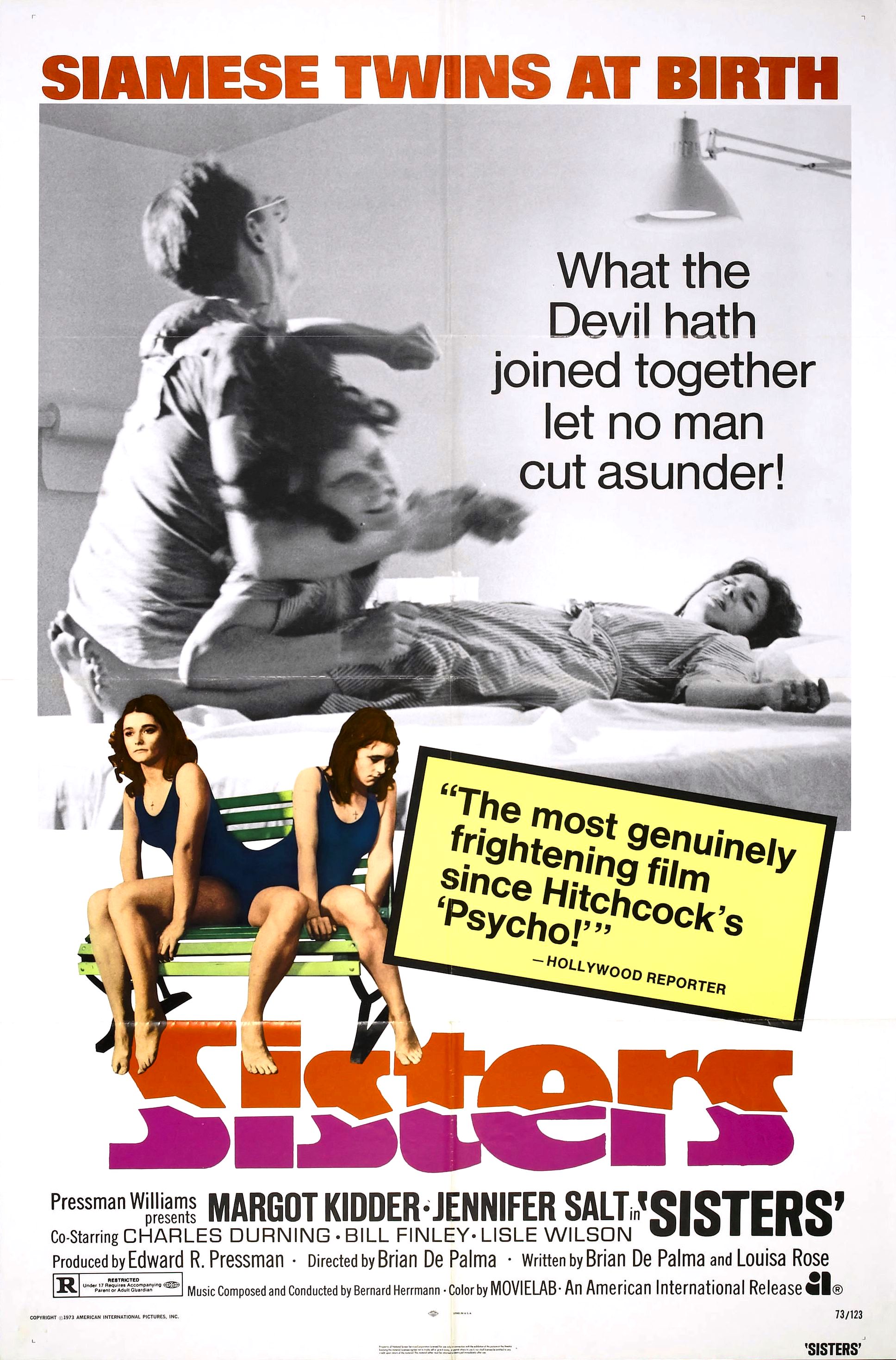

De Palma now likes to think of himself as “the last practitioner of Hitchcock’s language”. He wasn’t alone in the Seventies, with films such as Jonathan Demme’s Last Embrace (1979) almost equalling De Palma’s reputation-making homages Sisters (1973) and Obsession (1976) in updating Hitch’s fatalistic grip, while his near-peer Spielberg retained the knack when a child skips towards a time-bomb in Munich (2005). De Palma is now unique in the monomaniac complexity and sadistic success of his set-pieces, often using split-screen to ramp up the Rear Window-riffing, helpless voyeurism as murder or mayhem plays out.

De Palma now likes to think of himself as “the last practitioner of Hitchcock’s language”. He wasn’t alone in the Seventies, with films such as Jonathan Demme’s Last Embrace (1979) almost equalling De Palma’s reputation-making homages Sisters (1973) and Obsession (1976) in updating Hitch’s fatalistic grip, while his near-peer Spielberg retained the knack when a child skips towards a time-bomb in Munich (2005). De Palma is now unique in the monomaniac complexity and sadistic success of his set-pieces, often using split-screen to ramp up the Rear Window-riffing, helpless voyeurism as murder or mayhem plays out.

He presents this as a dispassionate exercise. “I did grow up in an operating room,” this surgeon’s son notes of his blood-drenched cinema. He’s “a big-brain, science kind of guy”, one of his actors, Gregg Henry, has noted; his schoolboy science projects were brilliant, and on-set he can be coldly uncommunicative, so precise in his plans that nothing more need be said. With the aid of romantically passionate composers such as Bernard Hermann and Pino Donaggio, scenes such as Carrie’s pig-blood-drenched Prom Night, Pacino’s flight from fellow gangsters through the New York subway in Carlito’s Way, the shoot-out around a pram’s Odessa Steps-style descent in The Untouchables, or Tom Cruise catching his own sweat-drop above a motion-sensitive vault’s floor in Mission: Impossible, then often become thunderously, operatically intense.

De Palma also takes tantalising inventory of the fact that Carrie was the director’s tenth film. His career began in the Sixties underground, with an initially chubby, crew-cut, charismatic young Bobby De Niro, pictured above right in The Wedding Party, as his star of choice, before Scorsese got him. De Palma’s early, funny ones, micro-budget, anti-Establishment and anarchic in the era of the Vietnam draft, help explain his scattershot, unsatisfied Hollywood career (he now works in France). The comedies’ glee with newly possible nudity continued into his thrillers, in which women have been stalked, slashed and drilled while, for Body Double, he outraged Hollywood’s caste system by test-screening a porn star. He still dismisses feminism as “the critical fashion of the day”, declaring once again here, unabashed: “I love photographing women…I love to follow them.”

De Palma also takes tantalising inventory of the fact that Carrie was the director’s tenth film. His career began in the Sixties underground, with an initially chubby, crew-cut, charismatic young Bobby De Niro, pictured above right in The Wedding Party, as his star of choice, before Scorsese got him. De Palma’s early, funny ones, micro-budget, anti-Establishment and anarchic in the era of the Vietnam draft, help explain his scattershot, unsatisfied Hollywood career (he now works in France). The comedies’ glee with newly possible nudity continued into his thrillers, in which women have been stalked, slashed and drilled while, for Body Double, he outraged Hollywood’s caste system by test-screening a porn star. He still dismisses feminism as “the critical fashion of the day”, declaring once again here, unabashed: “I love photographing women…I love to follow them.”

De Palma began as an informal record of the entertaining Hollywood yarns its subject told his younger director friends Baumbach and Paltrow, which they catch for posterity with an ironically static camera. His relaxed relish makes a change from his usual social discomfort, caught by Julie Salamon in her book on The Bonfire of the Vanities’ disastrous making, The Devil’s Candy: “When he remembered to be polite, the words sounded awkward, as though he were lip-synching phrases from a foreign language.” Though self-deprecating in tone, the documentary’s unchallenged stories settle scores, and mostly prove him right.

There are different insights in the short interview with a favourite actor, John Lithgow, pictured above, in the Extras of the recent DVD of De Palma’s ultra-Hitchockian, Oedipal Raising Cain. “Down deep, the spine of all his stories is real, almost Bergmanesque neurosis,” Lithgow, who is from a similar elite, intellectual background, observes. “He took his own obsessions, and put them all to work in his storytelling.” In one late, little-seen film, De Palma adapted James Ellroy’s The Black Dahlia. His own Fifties upbringing in a neurotically dysfunctional household, with a dominant, unfaithful father he stalked with a camera and threatened with a knife while his dad’s mistress cowered - briefly glossed in De Palma – is not so unlike the manic, haunted Ellroy. Hitchcock gave him the tools to purge and confess, to slash women and mourn, to kill and cure. With a surgeon’s steely control of his camera, he secretly let it all out.

There are different insights in the short interview with a favourite actor, John Lithgow, pictured above, in the Extras of the recent DVD of De Palma’s ultra-Hitchockian, Oedipal Raising Cain. “Down deep, the spine of all his stories is real, almost Bergmanesque neurosis,” Lithgow, who is from a similar elite, intellectual background, observes. “He took his own obsessions, and put them all to work in his storytelling.” In one late, little-seen film, De Palma adapted James Ellroy’s The Black Dahlia. His own Fifties upbringing in a neurotically dysfunctional household, with a dominant, unfaithful father he stalked with a camera and threatened with a knife while his dad’s mistress cowered - briefly glossed in De Palma – is not so unlike the manic, haunted Ellroy. Hitchcock gave him the tools to purge and confess, to slash women and mourn, to kill and cure. With a surgeon’s steely control of his camera, he secretly let it all out.

rating

Share this article

more Film

Love Lies Bleeding review - a pumped-up neo-noir

There's darkness on the edge of town in Rose Glass's sweaty, violent New Queer gem

Love Lies Bleeding review - a pumped-up neo-noir

There's darkness on the edge of town in Rose Glass's sweaty, violent New Queer gem

Nezouh review - seeking magic in a war

A movie that looks on the dreamier side of Syrian strife

Nezouh review - seeking magic in a war

A movie that looks on the dreamier side of Syrian strife

Blu-ray: The Dreamers

Bertolucci revisits May '68 via intoxicated, transgressive sex, lit up by the debuting Eva Green

Blu-ray: The Dreamers

Bertolucci revisits May '68 via intoxicated, transgressive sex, lit up by the debuting Eva Green

theartsdesk Q&A: Marco Bellocchio - the last maestro

Italian cinema's vigorous grand old man discusses Kidnapped, conversion, anarchy and faith in cinema

theartsdesk Q&A: Marco Bellocchio - the last maestro

Italian cinema's vigorous grand old man discusses Kidnapped, conversion, anarchy and faith in cinema

I.S.S. review - sci-fi with a sting in the tail

The imperilled space station isn't the worst place to be

I.S.S. review - sci-fi with a sting in the tail

The imperilled space station isn't the worst place to be

That They May Face The Rising Sun review - lyrical adaptation of John McGahern's novel

Pat Collins extracts the magic of country life in the west of Ireland in his third feature film

That They May Face The Rising Sun review - lyrical adaptation of John McGahern's novel

Pat Collins extracts the magic of country life in the west of Ireland in his third feature film

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

DVD/Blu-Ray: Priscilla

The disc extras smartly contextualise Sofia Coppola's eighth feature

DVD/Blu-Ray: Priscilla

The disc extras smartly contextualise Sofia Coppola's eighth feature

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

All You Need Is Death review - a future folk horror classic

Irish folkies seek a cursed ancient song in Paul Duane's impressive fiction debut

All You Need Is Death review - a future folk horror classic

Irish folkies seek a cursed ancient song in Paul Duane's impressive fiction debut

If Only I Could Hibernate review - kids in grinding poverty in Ulaanbaatar

Mongolian director Zoljargal Purevdash's compelling debut

If Only I Could Hibernate review - kids in grinding poverty in Ulaanbaatar

Mongolian director Zoljargal Purevdash's compelling debut

The Book of Clarence review - larky jaunt through biblical epic territory

LaKeith Stanfield is impressively watchable as the Messiah's near-neighbour

The Book of Clarence review - larky jaunt through biblical epic territory

LaKeith Stanfield is impressively watchable as the Messiah's near-neighbour

Add comment