Two leading ballerinas retired this week on either side of the Atlantic, Darci Kistler of New York City Ballet and Miyako Yoshida of the Royal Ballet. Both are in their mid-forties (not old for a ballerina) and each is an exemplar of certain best qualities of their companies, yet each seems to have outstayed their welcome in some way. Each farewell lights the touchpaper of argument as to whether those best qualities are institutional or personal - and therefore whether they can be preserved and transmitted - or whether the image that ballet neurotically clings to, of being ever-modernising, must imply that even luminaries go out of date.

Both women have suffered a watershed point when the politics of dance passed on and left them as relics. Kistler, 46, was the last of the muses of George Balanchine at New York City Ballet, and her farewell performance last Monday was the concluding moment of a 27-year mourning period that began with Balanchine’s death in 1983. Ironically, this was virtually the entire duration of Kistler’s career as an NYCB star, and with her gone from the stage, American dance-goers no longer have reference points to the ever-repeated mantra, “This is what Balanchine would have wanted” (a mantra that has simultaneously sustained and condemned City Ballet since 1983).

Yoshida, 44, was not of the same historical significance in British ballet, though most UK ballet-lovers accept contentedly that she was a serene, sweet and very rewarding dancer of traditional “English” qualities, a dependable team-player and reassuringly excellent. In the PR and image change that took place at the Royal Ballet at the start of the 21st century, Yoshida's decorous classicism, restrained physicality and lack of interest in modern work made her seem as old-fashioned as a girl in pearls inside a sleek city gym.

It appears inevitable in this almost deliberately transient area of theatre art - in which many people seem so anxious not to identify and actively preserve aesthetic qualities that they claim to prize - that ballerina retirements often evoke a trembling and a fearfulness for the future. In Kistler's case the fearfulness had set in long ago, possibly when the prodigy was even only in her early thirties. Eric Taub, in an intelligent, compassionate review of her farewell show for ballet.co.uk, summed up the dilemma in saying farewell: “The question is, how much to praise her, and how much to bury her?”

Like her near-namesake Darcey Bussell, Darci Kistler made her most brilliant impact as a teenager arriving prodigiously on stage with a bolder, shinier attack than that of her contemporaries, a strikingly beautiful face and remarkable legs and shapely feet. Born in 1964 in California, Kistler’s already individual musicality and glamorous sense of mystery at the age of 16 set her a further rank apart (she half-wanted to be an opera singer, she said), and commended her to the elderly Balanchine, for whom she was the final muse. He would talk to her about music, she said, not about dance.

Like her near-namesake Darcey Bussell, Darci Kistler made her most brilliant impact as a teenager arriving prodigiously on stage with a bolder, shinier attack than that of her contemporaries, a strikingly beautiful face and remarkable legs and shapely feet. Born in 1964 in California, Kistler’s already individual musicality and glamorous sense of mystery at the age of 16 set her a further rank apart (she half-wanted to be an opera singer, she said), and commended her to the elderly Balanchine, for whom she was the final muse. He would talk to her about music, she said, not about dance.

In fact, hardly had she become his protégée than he died, and most of her career was shaped by the choreography and artistic taste of her future husband, Peter Martins, the star dancer who inherited the NYCB directorship. The farewell-Kistler pieces by critics have united in regretting that both serious injury and the increasing distance from Balanchine’s era took a heavy toll on her artistic effects. (Above right, Kistler's final bow photographed by Paul Kolnik)

Alastair Macaulay in the New York Times opined that by rights Kistler should have been NYCB’s Fonteyn in renown and in aesthetic impact on the company, but that unlike Fonteyn, who was capable of wreaking magic spells for first-time spectators even in her fifties, Kistler had long become a relic of a former era for many young City Ballet-goers, rather than a lodestar. One reason postulated for this was Martins’ taste for speed and athleticism when Kistler's injuries were cramping her former daring; some commentators have pointed out that her artistry was rather superior to her husband’s, but his was the taste that prevailed.

British dance-goers had the merest glimpses of her in NYCB’s visits to London in spring 2008 and at the 2001 Edinburgh Festival, where her fastidiousness and bird-like feet (as I wrote for the Daily Telegraph) gleamed with an almost Russian mystique among the strong, lithe young New Yorkers of post-Balanchine generations. Unlike Fonteyn, Kistler was not a global ballerina; much as with Suzanne Farrell before her at City Ballet, she will remain New York’s legend, not nearly amply enough documented on video but hallowed in memory. The Balanchine legacy, draconianly protected in choreographic and pedagogic terms by his foundation and schools, is more elusive when it comes to the essence of his genius which he found refracted back to him by the 15-year-old Kistler - you either got or you haven't got style.

Watch a rare piece of film of Kistler as the Sugar Plum Fairy in NYCB's Nutcracker:

If Darcey Bussell’s retirement in 2007 was more of a landmark event for the Royal Ballet, Miyako Yoshida’s - which took place last Tuesday on the Royal Ballet’s Japanese tour in her native city of Tokyo - reminds us of the strong but undersung source of sustainment of British ballet that Japan has provided for decades, with their small, neat physiques and ingrained instincts for modesty and polished detail.

Yoshida (born in October 1965) has been the exemplar of the unexpected empathy in matters of tradition in classical ballet between the two countries. Tetsuya Kumakawa is another Japanese ex-Covent Garden star, who founded his successful company K Ballet with a raft of Royal Ballet men and British ballet values. Yohei Sasaki has been a valuable classical soloist for years at the Royal Ballet (and also retires this year), Nao Sakuma is BRB’s present leading ballerina, while Japanese talents pepper Scottish Ballet, Birmingham Royal Ballet, English National Ballet, The Royal Ballet and Northern Ballet Theatre.

The Japanese taste for restraint and grace was a powerful stimulus to that influential guru of British ballet Sir Peter Wright at Sadler’s Wells/ Birmingham Royal Ballet, and in an interview with me for the Daily Telegraph, he described Yoshida as his Desert Island dancer: “In a way I find she almost understands the English style more than the English do.” She became the unrivalled queen of his magnificently traditional stagings of the great classics, especially The Nutcracker, Swan Lake and The Sleeping Beauty, before moving to London 15 years ago.

Her career at the Royal Ballet has been a minor-key achievement in comparison with those of her versatile contemporaries Sylvie Guillem, Bussell and Viviana Durante and younger, more charismatic dancers such as Tamara Rojo and Alina Cojocaru. She is not attracted either physically or temperamentally to modernist work, and the Ashton rep in which she made her most natural fit draws less interest outside ballet devotees.

But Yoshida learned to combine her porcelain preciseness and romantic musical instincts to create a performance style of classical accuracy that also gradually emitted an unexpected degree of dramatic fervour. That her final performance with the Royal Ballet this week in Japan was in MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet is apt - Yoshida used physical reticence and docility with surprising effectiveness to distil and focus the raging emotions of a desperate teenaged girl. If Kistler’s later career was a slow decline, Yoshida’s was a steady plateau of quiet sweetness that inspired a widescale affection for her.

Married to a Japanese football agent, Yoshida has said she wants to settle back in Japan and coach her “English” style to her compatriots - she will be an exemplary model for them in technical terms. Once again, though, it's the unteachable that matters: the spirit, the perfume, the indefinable duende which only the individual can uncover and deploy, sometimes without even knowing they're doing it.

Watch Yoshida as the Sugar Plum Fairy with Irek Mukhamedov in Wright's The Nutcracker for Birmingham Royal Ballet:

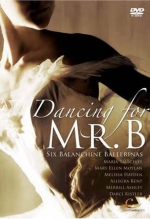

Darci Kistler dances on the film of George Balanchine's The Nutcracker and is interviewed (with performance footage) on Dancing for Mr B - Six Balanchine Ballerinas

Darci Kistler dances on the film of George Balanchine's The Nutcracker and is interviewed (with performance footage) on Dancing for Mr B - Six Balanchine Ballerinas - Miyako Yoshida dances on films of Wright's The Nutcracker with Birmingham Royal Ballet (1994) and the Royal Ballet (2000) and Ashton's Ondine with the Royal Ballet (2009)

Add comment