Quietly, without pomp and fanfare, Ashley Page has been mustering a balletic strike force over the border in Scotland. Scottish Ballet has launched the new ballet year with a programme that trumps anything else offered in Britain as a season opener, two demanding and brilliant works of the past (well done) and the gamble of a new creation of dance, music and design.

Compared with the opening offerings of English National Ballet and the Royal Ballet - and even with the lively Birmingham Royal Ballet opening programme (of which more tomorrow) - this combination of Ashton’s miraculously stylish 1947 Scènes de ballet, Page’s own tremendous 1995 Fearful Symmetries and a Val Caniparoli premiere is a bravely varied and ambitious three-course dinner - and with an attractive musical confidence too. After all, Stravinsky’s Scènes de ballet and John Adams’s Fearful Symmetries are two big scores, and it was fine to hear last night the Scottish Ballet Orchestra handling both with such dash under Richard Honner.

There is hardly a more gorgeous or mysterious opening scene in the art form than that first sight in Scènes de ballet of men in curious playing-card tunics standing in jagged poses with oddly linked arms before a surreal viaduct. It is a Forties ballet, and the sight redoles of a dark night-time fantasy place - a much more intriguing social milieu than today’s where there are so few mysteries. Like the oddly curlicued pillars either side, the men’s formal jumps and twiddling footbeats have a faintly off-kilter feel and when the women flood in on a swirl of strings, one gasps at their chic - pale blue tutus marked strongly with black and white, pearl chokers and large black berets plumed with white pearls. One almost smells Mitsouko.

The ballerina, in yellow, has no beret, poor love - but she declares her superiority by conquering all the five men with her range of classical wiles like a Princess Aurora at a slightly racy party. Scottish has a gem in Tomomi Sato, now, in spite of her tiny size, growing into a major classical ballerina. Last night she danced with a teasing exactness and bird-like lightness, her smile tinged with mischief and feminine allure. (Sato pictured right with Adam Blyde and company)

The ballerina, in yellow, has no beret, poor love - but she declares her superiority by conquering all the five men with her range of classical wiles like a Princess Aurora at a slightly racy party. Scottish has a gem in Tomomi Sato, now, in spite of her tiny size, growing into a major classical ballerina. Last night she danced with a teasing exactness and bird-like lightness, her smile tinged with mischief and feminine allure. (Sato pictured right with Adam Blyde and company)

I am surprised and grateful that the Edinburgh audience did not break the spell with applause, as it allowed one to notice better the furtiveness of the corps de ballet’s behaviour, the odd signals they seem to pass between them of a hostility to the ballerina (mocking bows that refuse to go in unison, a pecking mock-obsequious walk) - this subtext adds to the sense of constant disruption and secret disorder under the geometric patterns that’s part of the spell of this amazing ballet.

For Page, Scottish's director, to field this work at all is a declaration of bold classical ambition, and though I smelt fear in the ranks rather than joy at their exacting steps and precise formations (diamonds, squares, triangles, bisected circles - please sit upstairs if you can), the company came through tidily enough on their feet, and one could sigh with pleasure at the astonishing meshing of dance, music, human quirkiness and theatre into some kind of exquisite gesamtkunstwerk. Thank you, Scotland.

In fact, the overall impression of the night was that Scottish Ballet has some damned glamorous girls in there. This was writ large in Page’s terrific Fearful Symmetries, in which it’s impossible to banish one’s indelible memories of the great Irek Mukhamedov, for whom the choreographer made the piece 15 years ago, so I apologise if I can only say that Erik Cavallari did as well as anyone could. Page, who spent many years flamboyantly parking various trends on his ballets at Covent Garden, never made anything more fully digested than this most flamboyantly stylish of all

In fact, the overall impression of the night was that Scottish Ballet has some damned glamorous girls in there. This was writ large in Page’s terrific Fearful Symmetries, in which it’s impossible to banish one’s indelible memories of the great Irek Mukhamedov, for whom the choreographer made the piece 15 years ago, so I apologise if I can only say that Erik Cavallari did as well as anyone could. Page, who spent many years flamboyantly parking various trends on his ballets at Covent Garden, never made anything more fully digested than this most flamboyantly stylish of all

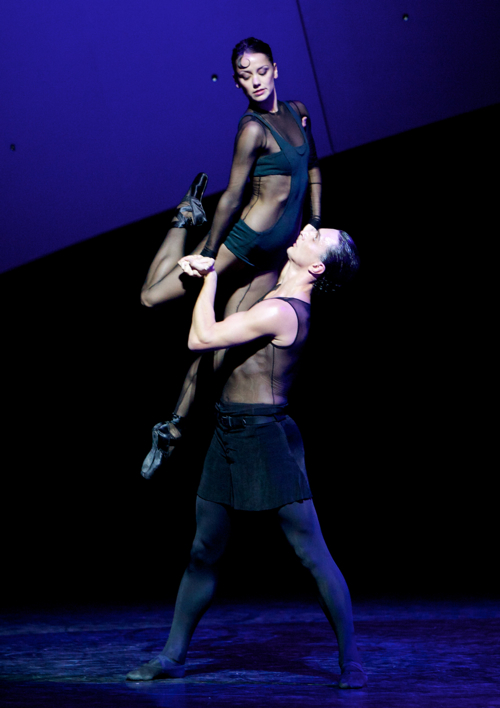

It makes great photos, of course, with its attention-seeking set, Antony McDonald’s eyewatering lime and aqua panels travelling slowly across the deep purple sky, and some of the sexiest costumes ever made for women, sooty dévoré-style leotards with sheer black tights and black shoes, worn with high, classy French pleats and diamonds. The music is a gorgeous propulsive racket full of earcatching instrumentation, the dancers look liberated, individual and full of sensual self-confidence.

Page’s attraction to the wiry, athletic William Forsythe school is obvious, but perhaps now - at this distance from then, and with Scottish Ballet dancers rather than London ones - I see less the posing and conscious desire to make a new statement than the careful organising of entrances and exits, the attentive musicality, the grading of the three pas de deux for the man and his three ladies (shades of Balanchine’s Apollo), and even the classical hauteur of the bearing (shades of Petipa’s Sleeping Beauty again).

It would be hard to find three more suitable glamour girls for the part than the dangerously languid blonde Eve Mutso, the wren-like Sato, and the elegant, intelligent brunette Sophie Martin (pictured left above with Cavallari), and Cavallari added to the hurling Bolshoi jumps a good enough echo of the intently supportive and interested partnering that Mukhamedov always gave, and which Page has written so strongly into this piece. If you want to see what Mukhamedov was like at his greatest, look at the Bolshoi film of Spartacus by all means for his rocket-propelled youth, but study Fearful Symmetries for a superb portrait of his magisterial completeness.

Sitting between these two landmarks, Val Caniparoli’s Still Life clarifies the abyss between true choreographers and dogged stepmakers. It tries very hard. It has all the elements that any brave artistic director wants: new live music, big design statements for great photos (pictured right), minimal lighting and about half an hour of action. It duly fields gimmicks including Japanesey paper birds flying on wires and a climactic moment when everybody strips off to underwear. It has the handicap to my ears of a too hardworking assemblage of chamber music for violin, viola, cello and piano by Elena Kats-Chernin, with certain tango elements but too much ungrateful scrubbing on strings to be rewarding to my imagination.

Sitting between these two landmarks, Val Caniparoli’s Still Life clarifies the abyss between true choreographers and dogged stepmakers. It tries very hard. It has all the elements that any brave artistic director wants: new live music, big design statements for great photos (pictured right), minimal lighting and about half an hour of action. It duly fields gimmicks including Japanesey paper birds flying on wires and a climactic moment when everybody strips off to underwear. It has the handicap to my ears of a too hardworking assemblage of chamber music for violin, viola, cello and piano by Elena Kats-Chernin, with certain tango elements but too much ungrateful scrubbing on strings to be rewarding to my imagination.

The piece falls into two halves, an exceedingly low-lit, posy part with seven couples in long gowns and skirts and paper birds being meaningfully released while dancers do about five per cent of their capability in limited movement, then a change of pace when they strip down to bronzy undies and become a little less self-consciously active about the place.

Meanwhile the birds start falling out of the sky, along with large shreds of paper that are perhaps feathers being shaken out of the Divine Being’s duvet or something - there is a glum note under the title to help one understand that “Mankind is a miserable bird; it tries to take flight, to be free, but falls to the ground, exhausted.” On the other hand, mankind also provides dance training, subsidies and art for us to go and enjoy the fruits thereof, for reasons opposed to misery. I try hard to imagine Ashton or even Page putting such a notion onto one of their pieces, and fail.

- Scottish Ballet's Geometry + Grace programme is at Edinburgh Festival Theatre till tomorrow, then tours to His Majesty's Theatre, Aberdeen, 1-2 Oct and Eden Court, Inverness, 8-9 Oct

- Read The Ballet That Began in the Bath, theartsdesk's feature on Ashton's Scènes de ballet

- Scottish Ballet's website for further information

Add comment