When the words "commercial" and "art" come together - as they do with the Bolshoi season currently at the Royal Opera House - odds are the glue between them is a three-word phrase "Victor Hochhauser presents". Victor and Lilian Hochhauser are the impresarios behind most Russian ballet seasons UK-wide, and they have a reputation for solid box-office commercial taste, which is easily dismissed as the safe option. But they are in their eighties now, and conservatism is forgivable. In younger, bolder, Cold War days, these cultural buccaneers brought Britain Richter, Oistrakh, Rostropovich, Gilels, Mravinsky, the Borodin Quartet and the UK debut of the Kirov Ballet (the one Nureyev defected from). In fact, without the Hochhausers, British cultural life for the past half-century cannot easily be imagined.

Victor (b 1923), CBE, is of Slovakian-Hungarian extraction, Lilian, a little younger, has Ukrainian family background - both are devout Jews, which has often raised questions over their dedicated promotion of artists from such an anti-Semitic country as the USSR. Yet the Soviet performers were dominated by Jews, Emil Gilels, David Oistrakh, Leonid Kogan, the entire original Borodin Quartet, the ballerina Maya Plisetskaya, among them. And so how the Hochhausers balanced their business aim to bring the Soviet artists whom they knew and were friends with to the Britain where protests were freely made about the treatment of Jews is just one of the many questions that float unresolved over the head of this mysterious and uniquely effective pair of impresarios.

In 2001 I interviewed the Hochhausers in depth about their career for a Daily Telegraph article which only scratched the surface of their activities. Since then Rostropovich, the cellist who played such a hand in their lives, has died, and the ageing Hochhausers have become a comfortable feature of the elite high-end art scene focused on the Royal Opera House. But what interested me was their sheer daring when they were young, breaching the wall into the Soviet Union - as Westerners, as Jewish Westerners, as two private individuals fired by the taste for doing something different, and making a lot of money out of a diabolical bargain with the most fearsome nation on earth.

They were David against Goliath. They have been condemned by prominent Jews, such as Bernard Levin, for their continuing profiting from Jewish musicians in a country that denied human rights to Jews, and (by me among others) for their excessively expensive seats which seem to favour the rich, smug event-hunters against the truly desiring, more discerning but poorer art-lovers.

Undoubtedly the Hochhausers got rich by it, but so - my god - did we, in a more lasting sense

Yet in the career of Victor and Lilian Hochhauser all the conflicts, dilemmas and contradictions come together in the single question - if you knew David Oistrakh was there, and you could get him to play in England, where he would benefit in money and reputation and a free love for music, what would you do?

Or, to put it another way, if you could use levers to enable a Shostakovich Western premiere that a great conductor told you might rescue a symphony from oblivion, would you confront the Soviet machine over it and risk your business?

There are no pure ethical answers in the world the Hochhausers dealt in, and undoubtedly they got rich by it, but so - my god - did we, in a more lasting sense. What we will do when they are no longer with us, what will happen to the special British relationship with the Bolshoi and Kirov Ballets, a relationship that we know puts these pivotal companies for the artform on their mettle, is a scary thought. The Hochhausers' ticket prices may make our eyes water, but thanks to their courage and enterprise in the 1970s I as a student heard Richter and Gilels, and saw the Kirov and Bolshoi, and it opened my eyes forever. Below is the first of two parts to the transcript of our conversation (which took part as they were about to promote a Kirov season, a Royal Ballet season and a season with Sylvie Guillem and La Scala Ballet).

ISMENE BROWN: When did you two meet?

ISMENE BROWN: When did you two meet?

LILIAN HOCHHAUSER: We met in early 1949. After a very short time decided that it might be a good idea to get married.

VICTOR HOCHHAUSER: You think she was a good choice? Do you approve of the choice?

It seems to me you are a very harmonious couple. But how do you work together?

VH Certain things that Lilian handles better than me. Certain specific artists that I cannot handle, and she can! I’m temperamental.

Because you are quite prickly, aren’t you?

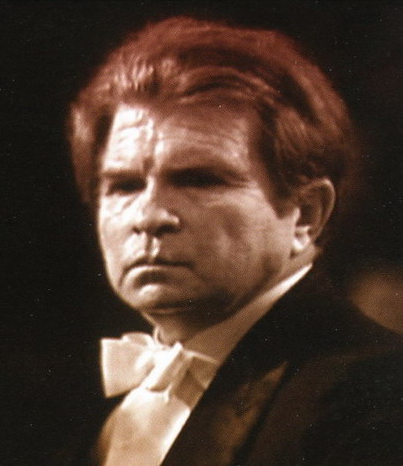

VH No, no, not prickly. But my temperament is, maybe, Continental. And what I think has happened is that certain artists like Sviatoslav Richter - I was very fond of him but this was a speciality of Lilian’s. Oistrakh, one or two others, the ballet companies especially. Certain things that I haven’t the right mentality to deal with. Also a lot of the detailed work.

LH Well, we met in 1949 [she smoothly overtakes him], and he had already started organising concerts.

VH In 1946, 45.

LH I was very interested in music. I thought, this looks like a good opportunity.

VH So you loved the music, not me.

LH Well... in equal measure. So we married in 1949.

VH December.

But you are Hungarian, Victor? And you came over as a child?

VH Hungarian is a rhetorical description - it’s a profession. My mother was Hungarian, and I was born in Czechoslovakia. My father was born in Slovakia. That part that changed every five minutes, Czechoslovakian, Hungarian, Austro-Hungarian. So we lived in this area of Slovakia where I was born. I was 15 or 16 when I came here, 1939, just before the war, with my parents, brother and sisters.

Was it the general threat there that brought you here?

VH It was more than a threat. It was the fact that Slovakia became part of the Nazi setup, a state under Hitler’s regime, very anti-Semitic. Jews were driven out or murdered. And the Prime Minister of the independent Slovakia was a former Catholic priest by the name of Jozef Tiso, who was hanged for war crimes. And other people. This nationalistic puppet state under Hitler became part of the Nazi German regime, and the order of the day that the Jews should be killed. My father, who had lived in Switzerland during the First World War, decided there was no future for us, and he uprooted himself. The only one in our family, and the only one to survive the war. All the rest were murdered. He came here in 1939, and applied to the Home Office for permission to bring us, and we did in May, eventually. Many friends here helped us. That’s how I am here still. And the rest of the my family are not here, alas.

My father was very fond of music but not a musician, he was an industrialist, like my grandfather. They had lived there for perhaps a century. A couple of years ago I went back to this place where I was born, took the children to this whole area of Slovakia - thought it would be interested for them to see their heritage. [To Lilian] You remember this?

LH Yes. Your heritage. MY heritage was elsewhere.

VH But in any case, she’d been there earlier because she took the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra to Hungary, and the BBC Symphony Orchestra on tours. We went to Prague and Bratislava.

LH And the Birmingham orchestra. In the Fifties. We took the BBC SO there in 1967, RPO was probably a couple of years earlier. And later Birmingham, which we took to Eastern Europe and Russia, and so on.

VH The BBC SO went with Pierre Boulez and John Barbirolli - an interesting event. [He tells me about it later.]

So how did you come from this uprooted background, in an industrialist family, to promote music?

VH Life is full of opportunities, sometimes missed opportunities - and you get a chance in this country to do things properly and well, which you don’t in other countries.

LH Basically you were asked to organise - it was before we met - a particular charity concert. That’s how it began and it was very successful.

VH It was with Solomon. My father knew his father, and he said I’ve got a son who plays and so on, and I had said, I want to organise a concert. And he asked Solomon. He agreed to do this recital at March 1945, at the Whitehall Theatre, and every single seat was sold out. It was wonderful, I felt it was the beginning. Eventually he had a stroke unfortunately, but he was a great great pianist.

Below Solomon plays the first movement of Beethoven's Appassionata sonata op 57 (YouTube):

Then came the Albert Hall, with Ida Haendel. But before that I met Haendel, Louis Kentner, Eileen Joyce, Moiseiwitsch, Myra Hess. Yehudi came in a bit later, in 1948. He came here at the end of the war, at the invitation of the Daily Telegraph, to do a series of three charity concerts, I went to all of them, one for the Free French, one for the British army, one other - all sold out. Then I had the idea of going to see Harold Holt, one of the old impresarios from the turn of the century, and he said to me, why should I give you my best artist? Then suddenly, he says to someone, "Make sure he gets it. And make sure he pays £1,000." You wouldn't get this today! And I was able to book Yehudi Menuhin for £1,000, and it was sold out. And I made a lot of money. He did every year for us four or five concerts. Then came the Russians.

So you two met, and...

VH The babies came along.

Lilian, were you to start with more occupied with raising the children?

LH No, I’ve always worked.

How did you divide the labours? Who’s the arty one, who’s the business one?

VH The baby one was on Lilian’s side. Ho ho! Sorry!

LH We were normal in that way. It was a question of doing what we had to be doing. We never consciously divided it. We would work in tandem or I’d have an idea and go and do it, or Victor.

VH Usually Lilian does the work and I do the collecting.

LH Right. You can say that again.

Who does the financial negotiations?

VH We both do it.

LH [corrects him]. I do.

So you are the tough one.

So you are the tough one.

LH Yes. I try [laughs slightly], I try. The point is we were being bold when putting on concerts from the time we met in the Forties, in 1949-50, and other things too - we toured with Mario Lanza (pictured right), for instance, which was quite historic.

VH And Gracie Fields too. Markova.

LH And Gracie Fields, yes. And also we arranged a very historic ballet season at the now defunct Empress Hall, which included the young Svetlana Beriosova (pictured below), who was 15, [Leonide] Massine, [Alexandra] Danilova, Frederic Franklin. We did Gaïeté Parisienne with Massine himself.

VH Markova and Dolin. What other companies. Mona Inglesby, wasn’t there?

VH Markova and Dolin. What other companies. Mona Inglesby, wasn’t there?

LH Anyway, there were all these seasons that we were doing. Then in 1953 Stalin died. And almost the same day...

VH Before you come to that there was the Vienna Philhamonic and Bruno Walter in 1949.

Was that the moment when you felt you had joined the major league in classical music?

VH Oh, of course.

These were the key artists that you booked when you felt you’d moved up, won the respect of the profession?

VH You are absolutely right. That would be the Yehudi and the Vienna Phil that put us on a different level, the Beethoven cycle with Yehudi as the soloist and Bruno Walter.

LH Our main interest was always classical music, so we pursued all the avenues there. But there were temptations on the side that were good fun like Mario Lanza, and we used to work very closely with Jussi Björling.

Did you ever have to pick him up off the floor?

VH Absolutely.

LH Oh absolutely. There was once we had to persuade him to go on to sing Bohème at Covent Garden, and he was really not feeling up to it.

VH The Queen Mother was there.

LH Was she the Queen then? Might have been. Anyway, we had to persuade him to go on. Poor man, he was the most wonderful tenor, but he had this terrible drink problem.

VH He did appear in the end.

Below: Bjorling, aged 25, sings 'Che gelida la manina' from La Bohème in 1936 (youtube):

LH He died too young, when he stopped drinking.

VH At 46, I think.

LH 46, or a bit more. So our main thrust was...

VH May I interject here? [He hasn’t stopped interjecting throughout Lilian’s words.] In 1949 we promoted Bruno Walter and the Vienna Philhamonic, and then again in 1951, we invited them back again. And Lilian went to the maternity home to deliver the baby.

LH 1950 it would have been...

VH Albert Hall. I was very nervous, of course. He was conducting a Beethoven symphony, he asked me, why so nervous? I said, my wife is now at Queen Mary’s delivering a baby. He said, "What are you going to call it?" I don’t know whether it’s a boy or a girl, I said. He said, "Relax. If it’s a boy call it Egmont. if it’s a girl call it Leonore." [Laughs uproariously.]

Below, Bruno Walter conducting Beethoven's Leonore 3 overture in 1941:

And you did?

VH We didn’t! It was a girl.

LH They were magnificent seasons.

VH And magnificent children.

LH There was Furtwängler, Josef Krips, Menuhin (pictured), and for three years successively we brought the Vienna Philharmonic.

LH There was Furtwängler, Josef Krips, Menuhin (pictured), and for three years successively we brought the Vienna Philharmonic.

Were you the only ones operating in that area of promotion?

VH Yes. Well, Harold Holt.

And you still are, really. You have a little competition, but not much - just Raymond Gubbay.

VH Well, he worked here for us.

I know. 10 months, 28 days...

LH ...three hours and five minutes, I know.

VH If he had worked with us for one more month, we could have taught him less arrogance, more humility.

But he was young, what can you expect of a 19-year-old?

LH That’s true. I still think we have the edge on quality.

Maybe, but let’s not get sidetracked here! Didn’t you do the Red Army too?

VH Many times.

LH When Stalin died Russia opened up. And just at that moment there was a cultural delegation here, which had the pianist Bella Davidovich on it, and Igor Oistrakh who was then 20.

VH He’s 70 today!

LH And we thought, how exciting, there’s an Oistrakh in the country. We got in touch with him and within three weeks we changed a concert we had planned at the Albert Hall and got Igor to play. He played Beethoven and Khachaturian, I think.

VH No, Khachaturian was with his father. Igor played Beethoven and Mendelssohn.

LH Well, anyway, whatever. He came and he played at the Albert Hall. That was the start. The following year 1954, we invited David [Oistrakh]. And from then on we had a very close association.

Listen to David and Igor Oistrakh playing a Wieniawski Caprice together:

But who opened it? Who was the person who got that door open? Was it someone in the Culture Ministry? Who said, now Stalin’s dead we can start?

VH We bombarded them. My father had already told me when he went to Prague about this wonderful violinist David Oistrakh. His fame preceded him.

Had you been trying to get him?

VH Yes, we bombarded the embassy with letters, but they never replied. Then Stalin died, and this delegation came here, and Igor went back and reported to his father... and then this artist came, with a whole entourage of spies and I don’t know what. Generally speaking it started with that first concert in 1953, with Igor Oistrakh, and then 1954 with David Oistrakh.

Did the public know about them?

VH David Oistrakh sold out in five minutes.

How did the public know about these hidden Russians? Were there records?

VH I don’t know. They just knew.

LH But look, they were from Russia, and anything from Russia was so exciting. [She protests at Victor going off to check something.] Oh do that later, when I go. It’ll take hours.

VH Carry on speaking, nobody’s stopping you.

LH Whatever he says, I know exactly when it was. 1953 it started, and for 25 years we virtually had a monopoly of Russian artists.

VH Practical monopoly.

Would you say the Soviets were desperate to show these artists, or did they have to be persuaded against their will? Was it the Minister of Culture?

LH Gosconcert.

VH I think they realised this was a wonderful export that could make money for them. And also show the great flag for the Soviet Union. But it was good money. The really great breakthrough was when they sent the Leningrad Philharmonic with [the conductor Evgeny] Mravinsky, that was such a success, to Edinburgh. And Lord Harewood [director of the Edinburgh International Festival 1961-65] decided as a result to go to Moscow and have a whole Shostakovich Festival and bring over all the greatest artists. Oistrakh, Gilels, Richter. That was in the late 50s.

LH 60 or 61.

You weren’t involved in the Bolshoi tour in 1956.

LH No, that was a direct exchange with the Opera House.

VH It was the government really. They wanted to open up.

This was under the Anglo Soviet Agreement?

LH, No there was no agreement then in 1956. It came long after we were worked with them. All our early dealings with the Russians were direct, not under the aegis of this agreement. We made contracts, but then later they started this agreement.

Were you surprised at the USSR suddenly opening up?

VH Absolutely, and what artists.

LH Yes. Because you have Richter, Oistrakh, [Emil] Gilels, [Mstislav] Rostropovich, [Leonid] Kogan. And then composers, [Dmitri] Shostakovich and [Aram] Khachaturian, and in his own way [Sergei] Prokofiev, who died the same day Stalin died, so we never directly met him. And as Victor says they were very very keen to maximise their income. At first they used to reverse the usual situation, take 90 percent of the fee and give the artists 10 percent.

And were these people fabulously expensive to get?

VH Oh yes, the proper market rate, comparing with Heifetz, Menuhin, Kreisler, these kind of people.

So did you pay a fee to them and then take the ticket take?

VH Yes, we paid them money and took the risk.

And that’s always how you work. There are more complicated arrangements, aren’t there, of sharing risk and marketing and so on.

VH We never share. We had to guarantee 10 or 20 concerts for Oistrakh or Rostropovich, or whoever, and we had to undertake to fill the theatres, and hopefully we would make money on it. By selling tickets.

What was the impact of these Soviet artists on the European and British scene?

VH Enormous. Astounding.

LH Not only were each of these people a genius on their own field but the public hunger for things Russian was huge. Russia had been a closed book for so many years that it had its own novelty and own momentum, quite apart from the gifts of these people, who were magnificent.

VH And not only orchestras - chamber orchestras too of magnificent quality, playing at the Bach Festival. People hadn’t heard this kind of playing before.

Did you feel terribly sorry for them, knowing the circumstances they lived in?

VH Yes, of course we felt sorry for them.

LH Yes, we felt very sorry for them. From today looking back on those days, it’s hard to remember just how frightening they really were. I mean, you knew when you went there that you were watched all the time, you were listened to all the time, you didn’t want to get anybody into trouble, because you knew they were living under this terrifying regime. And we had to deal, of course, and there were times we would sit in Moscow for four weeks at a time, dealing with people from Gosconcert and the Culture Ministry of Culture, who were beastly mediocrities, and yet were able to order these great people around and tell them what to do.

VH Example, when the Leningrad Phil first came to London, to play in the Edinburgh Festival and to London Festival Hall, I stayed there in the Europe Hotel in Leningrad, opposite the Philharmonic Hall, a wonderful hall.

LH The Europe is a super luxury hotel now.

VH And Mravinsky himself came to see me, along with another man, Ponomarev, who was a plant, but at least he was friendly with the conductor. And this conductor, a highly cultured man (pictured left), spoke perfect German, said to me, "Could you do me a favour? When you go to see Ekaterina Furtseva, Minister of Culture, could you please say that you want us to bring the Shostakovich Eighth Symphony? Because we are not allowed to play it. We’ve asked, it’s been refused all the time, it’s too pessimistic. But if you say you want it, they may listen to you. And also if you say the BBC - who were going to broadcast it - insist on it too. It’s very important." The Fourth was also not performed. So I went to Moscow, saw the Minister, said the public was very interested to hear Shostakovich’s symphony, which was dedicated to Mravinsky. And they agreed. And this symphony had such a tremendous impact in London. Do you know it? [Note: Sir Henry Wood conducted the first British performance of Shostakovich's 8th symphony for a BBC radio broadcast in 1944.]

VH And Mravinsky himself came to see me, along with another man, Ponomarev, who was a plant, but at least he was friendly with the conductor. And this conductor, a highly cultured man (pictured left), spoke perfect German, said to me, "Could you do me a favour? When you go to see Ekaterina Furtseva, Minister of Culture, could you please say that you want us to bring the Shostakovich Eighth Symphony? Because we are not allowed to play it. We’ve asked, it’s been refused all the time, it’s too pessimistic. But if you say you want it, they may listen to you. And also if you say the BBC - who were going to broadcast it - insist on it too. It’s very important." The Fourth was also not performed. So I went to Moscow, saw the Minister, said the public was very interested to hear Shostakovich’s symphony, which was dedicated to Mravinsky. And they agreed. And this symphony had such a tremendous impact in London. Do you know it? [Note: Sir Henry Wood conducted the first British performance of Shostakovich's 8th symphony for a BBC radio broadcast in 1944.]

LH Also had the premiere of the Fourth as well. The 4th, the 8th, the 13th, the 14th and the 15th.

VH And the quartets too.

So the musicians knew you were a lever - you were able to get these pieces played!

VH Yes. And other pieces.

Listen as Mravinsky conducts the UK concert premiere of Shostakovich's 8th symphony with the Leningrad Philharmonic at the Royal Festival Hall, 23 September 1960 - Allegretto.

Listen as Mravinsky conducts the UK concert premiere of Shostakovich's 8th symphony with the Leningrad Philharmonic at the Royal Festival Hall, 23 September 1960 - Allegretto. - Find the recording on Amazon

You could feel proud of yourselves for getting these pieces played. Not just the Eighth Symphony of Shostakovich.

VH First time, first time. Also Prokofiev’s Sixth Symphony and The Fiery Angel were performed, premiered in London. Also some of the late Shostakovich quartets. But you know the Soviets always wanted big positive pieces like the Fifth symphony.

LH The 13th symphony was positive. We had Yevtushenko here.

VH You’re right. For many years it was not allowed in Russia.

Did Shostakovich contact you about it?

VH He stayed here!

LH He was our guest on four occasions.

VH We knew him very well.

LH Well, as far as you could know him very well. As Rostropovich says, the more he receded into the background the more you wondered if you really knew this genius. But we did. And we organised a large Russian-Soviet music frestival all over the country, 40 concerts, and he was the guest of honour. Always very nervous. A very unhappy and nervous man.

VH. He was ill, went to hospital here. Very nervous. But also with a good sense of humour. We went to Edinburgh with him.

Was he relaxed in the UK?

VH No, I think, never relaxed, by nature.

Did these people ever shake off that sense of being watched all the time? What about Richter?

VH That’s another story. Lilian will tell you that.

LH Richter was unique. Richter didn’t care about anything or anybody. He did just what he wanted to do, and they couldn’t touch him. It’s true that his wife Nina Dorliac, the singer, used to do all the negotiating for him.

VH He never went to the Ministry, refused ever to see them.

LH I used to say to Richter, what shall we do with these people? And he’d say, shoot them.

VH [triumphantly] He didn’t want to go near them. Never spoke to them.

LH He was the freest spirit you could imagine. He wasn’t allowed to travel until 1960, they didn’t let him leave the company. We brought him here in 1961, for the first time. He played what he wanted to play, went where he wanted to go.

VH He shook off his sputniks!

Below, extract from 'Richter, the Enigma' - he plays Chopin and Schubert and talks of his feelings of dislocation (medici.tv):

Did he stay here too?

VH Yes.

And what wat he like? I hear he was a great one for sleeping under people’s tables in the USSR!

LH He was the most wonderful man. Great sense of humour. And he was brilliant in many fields. He was a good painter.

VH An architect too.

LH He was a polymath.

VH and you are talking to Lilian and me, who suffered when he cancelled so many concerts. And yet when he appeared you’d forget all these things. We lost money because he cancelled, we couldn’t even insure him any more. But he was such a great man.

What, you could insure against him cancelling? Who with?

VH No more. Lloyds.

LH, Lloyds, or someone.

VH Yes, Lloyds. We never claimed. No, there was a claim once. When you could claim was when they cancelled because the spies were kicked out and all the shows were cancelled, a big loss. Insurance covered that.

When was that?

LH When the Czechs, the Red Army...

VH No, the Czechs were another story.

LH 68.

VH 68 was Czechoslovakia. Spies were 71.

LH The other point was how loyal Richter was. I mean, for 14 years we were persona non grata with the Russians, from 74 until perestroika our names were erased, and we were not to be mentioned.

VH. Two reasons. The Jewish question was getting very hot. They thought we should protest against the Jewish artists protest.

People supporting the dancer, Valery Panov [who went on hunger strike in 1974 to win his right to emigrate].

VH They wanted us to protest against the demonstrations.

LH They wanted us to employ a kind of private army to protest against the demonstrations.

VH The embassy. Furtseva.

LH Which we were not prepared to do.

VH And they said, okay, in that case you can’t have our artists. I said, go to hell.

LH And then Rostropovich left the USSR just then and stayed with us for a year.

VH That also they didn’t like.

Was he your closest friend of those people?

VH Oistrakh was a great great friend. But Rostropovich too, yes, very much so.

LH We were very close. Worked with him since 1956, and still work with him. And they were very angry with us, and simply cut off communication. And Richter never came here, simply refused to come to England altogether, he wouldn’t come if we weren’t organising his concerts.

VH And Oistrakh died in 1974, but he wouldn’t have come either unless it was us.

LH Furtseva died the day Oistrakh died.

So when was Richter’s last concert with you? I remember queuing at the Festival Hall in what must have been 75.

LH It might well have been.

My entire faculty at the Royal College of Music went to queue from 5 am.

VH He was such a remarkable man, despite our suffering. He was also a great poet. He wasn’t easily friendly, but those who knew him knew what a great personality he was. One day we were going to do this festival, the two governments, British and Soviet, signed an agreement to exchange festivals, under the cultural agreement. So naturally the British were going to send Benjamin Britten and John Lill and John Ogdon and the London Symphony and Walton and Barbirolli. The best we’d got. They were also going to send the best artists from there. I went there to Moscow and there was a deputy minister in charge of the festival in England. And he said to me, "Here is the plan. Here is Gilels doing Tchaikovsky number 2, and a Prokofiev quartet, and there would also be a major orchestra with Svetlanov, and here is Oistrakh playing the Shostakovich violin concerto" - which we also introduced to Britain. We also did the cello concerto with Rostropovich in this country - another story! Mustn’t get mixed up.

Now it’s important for the Soviet government to send Richter but Richter said, "Well, I don’t want to play. In any case, this year I don’t want to play Russian music. I want to play Schumann, Grieg." And the minister says furiously, "How can you refuse to play? Soviet prestige. Maybe play with the Borodin quartet or something." Anyway Richter refused to play. But when I saw this plan from Bukharsky, there was Richter on the plan. When I saw Richter, I said this, he said, "I know nothing about this, I’m not playing." So we were in dilemma. We went to the Minister and said, "I cannot advertise this unless I know whether Richter is really coming or not." "If we say he is coming, he is coming." I couldn’t tell him that the man himself had told me "No". And nothing in the world would shake Richter when he had made up his mind.

So there was the season with that event. Do you advertise it or not? I knew he wasn’t coming, but I couldn’t tell the Minister he wasn’t. Breaking faith with the public - or betraying a man who you had a relationship with? Of course I advertised it, and of course I had to give the public their money back. But Richter wasn’t interested in all these nuances and things - he was only interested in the music.

What about Emil Gilels (pictured right)? Was he easier to deal with.

What about Emil Gilels (pictured right)? Was he easier to deal with.

VH No.

LH No. He was very difficult.

VH He was a great artist and we were great friends. I always visited him, and always stayed with him and his wife. You know he was Leonid Kogan’s brother-in-law. Mrs Gilels was Kogan’s sister. Gilels and Kogan didn’t speak.

Because Kogan spied on him when they were in a trio - Rostropovich told me that.

LH That’s right.

VH That. And other things too.

The fact is that Gilels was a great artist.

LH Fantastic. A fabulous artist. He suffered a little bit with Richter’s fame.

VH He could never accept the fact of being number 2. Very bad to be number 2.

But Richter admired him very much.

LH Richter did admire him very much, and Gilels had no reason to be jealous, but it was in his nature.

VH It’s bad to be number 2. Number 3 is all right.

LH Well, I don’t think Gilels was number 2.

Gilels and Richter, for me, were equals. I loved them both.

LH Gilels was just fantastic. He had though this feeling that he was number 2. He never was number 2. And when he came here he was just wonderful.

VH But Richter was an occasion; Gilels was just a great concert.

LH Yes, because Gilels didn’t cancel so much, that’s why!

Gilels plays Rachmaninov Prelude op 23 no 5 in the Great Hall, Moscow Conservatoire (sound and picture are slightly out of sync):

You liked the prima donna type?

VH No, Richter wasn’t a prima donna. He was a genuine eccentric, a genuine poetic type. He just wanted to play music, do what he wanted to do.

Not really reliable. From your point of view, you needed that.

VH Actually you hardly had to advertise him to sell the tickets, and he’d never give you the programme until a few days before he arrived.

I’m amazed you kept your patience.

VH For Richter, you do. Wouldn’t you?

LH What about one of the last concerts? Festival Hall, television, sold out. A great event for everybody. Then suddenly three hours before the concert a telephone call - it was a Bank Holiday - and it was Nina’s voice, and I knew that was a cancellation voice. “Lilian.” I knew that voice, that sound meant trouble. “Er ist krank.” He is ill. he can’t play. It was three hours to go. And I had to find somebody in that time to get the possibility of another date to substitute, then rush to the Festival Hall, get placards made and set up, saying ”Money back, or return to the next concert”.

VH They all came back to the next concert - no money was refunded.

LH Two weeks later.

What did he like to do, when he was staying with you?

LH He didn’t always stay with us. He did on occasion. He liked to be on his own, he’d practise sometimes up to 10 hours a day. He was a loner. He’d go walking off in the woods nearby. He wasn’t a man who wanted to be bothered.

Rostropovich was the opposite, so gregarious.

LH Total opposite. Very gregarious, very gregarious.

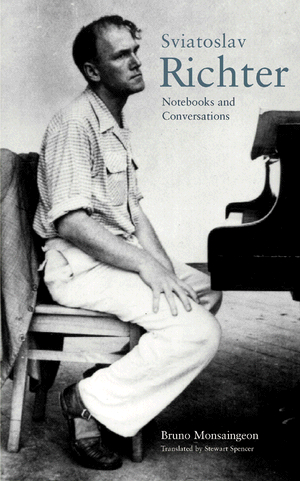

VH Yet they played together in Edinburgh, and here. Richter was a remarkable man if you read that book by Bruno Monsaingeon. It is Richter, no question, but the only thing I worry about is many of those things in it he would never have said in public. Richter would have edited that book. He would not have approved of all these remarks being published.

VH Yet they played together in Edinburgh, and here. Richter was a remarkable man if you read that book by Bruno Monsaingeon. It is Richter, no question, but the only thing I worry about is many of those things in it he would never have said in public. Richter would have edited that book. He would not have approved of all these remarks being published.

LH I think it’s a fantastic book, amazingly fantastic book. I don’t agree with you one bit.

VH He says some nasty things about artists, very nasty things, and it doesn’t add to...

LH Some sharp things, some of which he might have taken out. But let’s not, I’m telling you this book is completely unique. It’s all of Richter’s remarks, which are fantastic.

VH But he said these things without any record.

LH All this objection is quite petty. I think it’s quite fantastic.

VH The artists who are mentioned in there, even Rostropovich.

LH Well, we all knew they fought, didn’t we?

Tensions weren’t just musical.

VH That Karajan recording of the triple concerto...

I though that story was hilarious!

LH He said, there we are [Rostropovich, Oistrakh, Richter] in that photo sitting grinning like idiots. That book is a masterpiece, and you will never read such a thing again. So much of what he says is true, he gets to the heart of things, is not deflected.

VH But Ashkenazy, for instance...

Yes, but you see Richter’s remarks on people like Ashkenazy or Gidon Kremer or Tatyana Nikolaeva or Zoltan Kocsis, and it challenges the way I think about these people. I think, I must listen to their playing again and see why Richter might say this. But there’s also taste - you can’t always aaccount for it.

VH But all this he says, he says...

LH Yes, it is, Victor. I tell you I think any objection you make is not valid.

It’s not gossip, nothing that Richter says is gossip - it’s considered opinion. His generosity. He makes you want to die to hear Kocsis. And he makes a great remark about an old colleague of mine at the RCM, Jan Latham-Koenig.

LH Oh yes, the conductor.

VH Really? And of course about Oistrakh and Barshai.

LH But his whole approach to recordings and music is also fascinating.

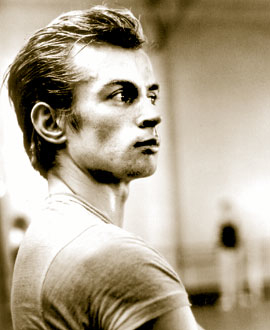

And his approach to ballet - which leads us on to the next subject... 40 years ago you brought the Kirov over. First ballet event for you. Tell me, must have been so exciting, and then the star attraction, Rudolf Nureyev, defects two days earlier.

LH Yes, in 61 we were very young, actually; we were putting the Kirov on at the Royal Opera House (poster pictured right), and it seemed unbelievable that this was happening. We went to the airport to greet them, and what did we see but long faces. On that very day, that very morning he had jumped the barrier in Paris. Somebody’s head would roll, and there were [the artistic director Konstantin] Sergeyev, very worried, and [ballerina Natalia] Dudinskaya, and an awful man called Korkin. They were all terrified, because somebody would have to take the rap for it. In fact Sergeyev was sent away for a while, was blamed. You know, it’s funny, you were saying, how do you know about someone? Rudolf was only 23 or 24, and yet everybody knew that he was a great dancer; so we featured him in our brochure, never having seen him before or met him. And he didn’t turn up, of course. The season went on.

LH Yes, in 61 we were very young, actually; we were putting the Kirov on at the Royal Opera House (poster pictured right), and it seemed unbelievable that this was happening. We went to the airport to greet them, and what did we see but long faces. On that very day, that very morning he had jumped the barrier in Paris. Somebody’s head would roll, and there were [the artistic director Konstantin] Sergeyev, very worried, and [ballerina Natalia] Dudinskaya, and an awful man called Korkin. They were all terrified, because somebody would have to take the rap for it. In fact Sergeyev was sent away for a while, was blamed. You know, it’s funny, you were saying, how do you know about someone? Rudolf was only 23 or 24, and yet everybody knew that he was a great dancer; so we featured him in our brochure, never having seen him before or met him. And he didn’t turn up, of course. The season went on.

What were your feelings at that point?

LH To tell you the truth, we were feeling vaguely upset, but we didn’t realise what the ramifications would be for the company and it was so exciting to have all these wonderful dancers turning up. So though there was a pall, we didn’t feel bad enough to spoil the season. And they rearranged the casting, and it resulted in Natalia Makarova dancing her first Giselle at 18.

And Yuri Soloviev was there, he was recognised as a great star.

LH Soloviev was a great dancer.

VH Killed himself.

LH And Kolpakova was there... the fact of the matter is that it was such a huge success that it wasn’t ruined by Nureyev’s defection. (Nureyev, pictured left)

LH And Kolpakova was there... the fact of the matter is that it was such a huge success that it wasn’t ruined by Nureyev’s defection. (Nureyev, pictured left)

Did you feel impatient with him, or not surprised?

VH I went to see him in Paris. He had really wanted to come to London.

LH No, we never felt angry with anyone who defected! [laughs]

Even if it blighted your bookings.

LH Yes, even so. One could not denounce anyone who wanted to get out otf that country.

VH And Natalia Makarova, of course, came to our house and told us she was going to leave [in 1970]. When she defected the Ministry was very angry with us, told us we should have hired police to make sure, keep an eye on them. We told them, it’s your problem if you want to keep your artists under surveillance. (Makarova pictured right in Giselle 1975, photograph by Walter Stringer)

Did they ever put any pressure or surveillance on you?

Did they ever put any pressure or surveillance on you?

LH No. But in 74 Furtseva was quite open that we should have kept an eye on the people coming backstage. At the time Makarova and Baryshnikov were here, they were very worried that Baryshnikov would defect, but whilst they were watching him, Makarova disappeared. They weren’t watching her. In 74 the reason was the Panovs, who were causing the demonstrations, and Laurence Olivier was walking up and down St Martin’s Lane demonstrating. And Furtseva was furious and said we should have done something to avoid these demonstrations.

VH Protesting against them.

LH The only thing I could think of was they wanted us to hire a police force. We would not have done it anyway.

Did they watch you? But they must have known artists would stay here?

LH Most artists stayed at the hotel. Only our very closest ones stayed with us, for a day or two. They were watched.

VH We used to live in Holland Park and had a small flat there as well.

Did you see men in bad suits walking around, trying to look inconspicuous?

VH Yes, they came with the company.

LH Of course we were watched. Everybody was watched.

Was your phone tapped?

LH I never noticed that. It may have been, but I never noticed it.

VH I told them, if you don’t trust the artists, better keep them at home. We cannot put on this sort of police force. I remember an officer came to tell me they didn’t like my personal association with the artists.

LH The fact of the matter is that we were very cognisant of their problems and we sympathised with them deeply. These people were our close friends, and they would confide in us. We did what we could - we would help financially, or do all sorts of things. Don’t you agree?

VH I don’t remember. I remember sometimes we had to pay for their wives’ upkeep.

LH No, I mean, when they were given 10 percent of the fee we would help them, sometimes. No, we understood what pressures they worked under.

VH Oistrakh came with his wife Tamara. He was expected to pay for her, for the fare, everything. They knew that they could not trust any foreign impresario, so they kept an eye on the artists, but they could not keep an eye on all the artists all the time.

Did you ever think you were being watched or shadowed?

VH I don’t know. I don’t think so. I know they didn’t approve of my association with the artists, but they knew that couldn’t be helped. In the end, all they could do was tell me, don’t be friendly with Oistrakh. Or don’t be friendly with Richter. After a while they gave it up.

LH Shouldn’t we be doing general questions about ballet?

OK, back to Nureyev’s defection. In one of the biographies of Nureyev, it says you are named in KGB files as having helped arrange Nureyev’s defection.

LH Really? How interesting? No, we had nothing to do with it.

VH What book is this? I didn’t see this book.

Peter Watson’s; says you had an associate in Paris called "Mr James" who, under cover of working for you on the London tour, introduced Nureyev to a CIA plant, who was pretending to be a newspaper editor.

LH [listens intently] No. The only James we knew was Sir Kenneth James, who was the ambassador, I don’t think he was in Paris. We really had nothing to do with Nureyev. We didn’t know him, you see, knew nothing of him.

The other story in another biography is that you threatened to sue Nureyev if he danced in Paris the same week he was supposed to be in London with the Kirov.

VH What?

LH Who - we?

It says in Diane Solway’s biography of Nureyev, which is thought authoritative - on page 169.

LH No.

VH I think we must read some of these books.

Because he danced Sleeping Beauty in Paris on the opening night of the Kirov's Beauty in London.

LH To tell you the truth, we had nothing to do with Nureyev for years and years. We couldn’t. Because if you wanted to deal with the Russians, you couldn’t have any dealings with Nureyev. So we didn’t. Until 1974 we had hardly any contact with him.

VH No, we booked him before, in 73, I think. We were cut off in 75.

So did you feel that after that cut-off there was enough quality Russian artistry free in the West to go on with them without the Soviets?

LH Not quite as simple as that. Because we were attached to our friends in Russia, attached to Richter, attached to Oistrakh. In fact I was forbidden a visa to go to Oistrakh’s funeral. I was in Amsterdam, where he died. I was helping to make arrangements to help fly him back to Moscow and then they wouldn’t give me a visa to go to the funeral. So from a personal and emotional point of view, it was very hard for us, this cutting off. From all other points of view, we simply found other opportunities. For 10 years or so we had these wonderful Nureyev and Friends tours; and we brought over the Chinese acrobats. It might have been 75 or 75. 74 the Bolshoi was at the Coliseum. We presented Nureyev at the Coli for the first time in 76, and that went on for 10 years.

VH Friends, and not only friends. Also many people who were not friends.

Such as?

VH It is true to say that many were not his friends [laughs]. But it is true we had many other companies.

In that year, 1961, you also presented Richter’s debut recital in London? Just after the Kirov?

VH It was June or July, I think. Around the same time.

So did the Nureyev defection knock your relations with Moscow at all?

LH No, no, not at all.

VH If the KGB thought we were involved, why did they let us go on dealing with Moscow?

LH No, because they only started to shake when they thought we were really involved in Rostropovich’s defection. That actually wasn’t there. We were only there to give help, not to make things happen.

VH He stayed in our house!

LH He stayed with us and his wife and children.

VH They were very angry.

LH Despite the fact that he was the greatest artists of any day, he had no schedule to his life.

VH He phoned us up from Moscow, has problems, the Sakharov business, and Solzhenitsyn was staying in his dacha. He was coming to London, could he stay a while? He originally came officially only for a year. Then his wife and the two daughters came, and then they all stayed with us.

A Rostropovich obituary summary of his life on Montreal TV in 2007:

That was when you knew you were burning your boats?

LH No, we didn’t think about that, i don’t think. We were just doing what we thought was right. In 61 it was different - it was deep communism, really deep communism. We couldn’t have dealt with Nureyev. But later on we came to the conclusion that we must do what we wanted to, not be governed by them.

Did you feel they needed you more than you needed them?

VH Because we had the artists’ trust. Very much so. And we paid them good money.

LH I think they did.

Because you had the entree to all the great theatres.

VH Exactly.

LH For 12 years after we stopped there was no cultural representation here of Soviet artists at all.

How much money do you think they made over the years from these artists?

VH I don’t know. But the fact is that it made it possible to get the great artists over here, which is much more important than whatever they spent the money on. To have Richter here, Oistrakh, Rostropovich, was much more important.

In your relationships with these artists, did they ever express gratitude to be performing in Britain?

LH, Yes, but it was two-way. Because we were so grateful to have their artistry here, and they were happy to have people who understood their problems. Our relationship wasn’t only commercial - we were heavily and deeply involved with these artists.

VH We couldn’t help it, talking with them almost every day on the phone, arranging their tours. With Oistrakh we met in every country in the world. Of course he hated the system, and I think we may have been his closest friends anywhere.

LH I think so.

Below, a ceremonial performance of Vivaldi's Concerto for 4 violins in 1966 Moscow by David Oistrakh and Leonid Kogan and their sons Igor and Pawel:

How did Oistrakh relax? Go down the pub?

LH [laughs] I couldn’t visualise David Oistrakh in the pub.

VH He used to play chess. He liked to walk a lot. He liked to gossip - he was a wonderful gossiper. Talked a lot of politics.

Did they manage to see other concerts in London?

LH Obviously they would, but they didn’t have a lot of time.

VH I will say, Oistrakh went to Heifetz’s concerts; it must have been 1963, the last concert by Jascha Heifetz. He phoned me up, said, we must leave at a time when my minder is not around. He had an accompanist called Yampolsky. I got two tickets, phoned up, said Oistrakh would like to meet Mr Heifetz. Got back a message: yes, but understand, this is McCarthy time and everything, Heifetz will meet him but only very briefly. That was Heifetz being afraid! So we walked into the room, Heifetz shook his hand, he had his poker face, they said, “Wonderful performance." "I appreciate it,” but not as effusive as usually he was. He said later, when they became friends, “Please understand, this was McCarthy time.”

Part 2 next week: 'He was a real nasty apparatchik, but we needed each other

- The Bolshoi Ballet and Opera perform at the Royal Opera House 19 July-8 August. Grigorovich's Spartacus 31 (mat & eve) July, Petipa/Ratmansky/Burlaka Le Corsaire 2-5 August , Petipa/Gorsky/Fadeyechev Don Quixote 6-8 August; Tchaikovsky's Eugene Onegin 11-14 August. Read theartsdesk reviews so far: Spartacus, Coppelia, Serenade/Giselle.

Add comment