Why play a very substantial act of ballet music in concert? In the case of Aurora’s wedding entertainment from Tchaikovsky’s The Sleeping Beauty, there are at least three good reasons. It embraces the most inventive and unorthodox of divertissements in any ballet – the one in The Nutcracker comes a close second – and a symphony orchestra deserves the chance to perform at least a substantial chunk of what Stravinsky called Tchaikovsky’s chef d’oeuvre. Besides, you won’t have heard every sequence in any choreographed version, not even the very thorough one by Matthew Bourne, who includes more music than the big companies though rarely in the right order.

There’s not a dud or redundant number in the entire act, as Vasily Petrenko brilliantly demonstrated; even all the repeats were welcome. Frequent ballet-company casualties like the 5/4 oddity, so piquantly scored, for the Sapphire Fairy’s pentagram and the notes tossed around different groups of instruments that so impressed the young Shostakovich in Tom Thumb’s seven-league-booted escape from the Ogre proved as vital and astonishing as any of the big moments.

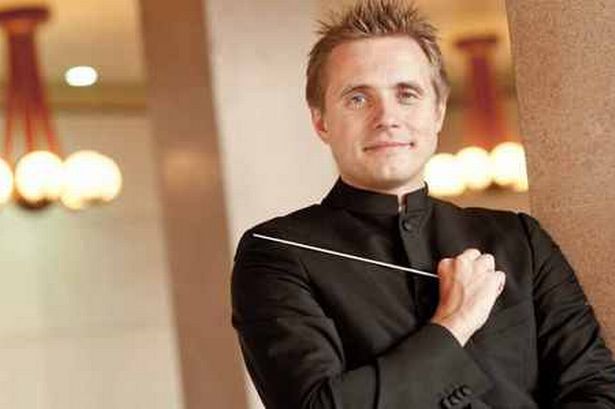

The Royal Liverpool Philharmonic’s first half saw its music director (Petrenko pictured right by Mark McNulty) embracing extremes of tempo, starting not with the cornucopious Overture to Humperdinck’s Hänsel und Gretel but the Evening Prayer it features, here minus the two voices, and the ensuing Dream Pantomime of Christmas-card Victorian angels, all at leisure in hazy euphony (a promised orchestral version of the Sandman's song did not materialise).

The Royal Liverpool Philharmonic’s first half saw its music director (Petrenko pictured right by Mark McNulty) embracing extremes of tempo, starting not with the cornucopious Overture to Humperdinck’s Hänsel und Gretel but the Evening Prayer it features, here minus the two voices, and the ensuing Dream Pantomime of Christmas-card Victorian angels, all at leisure in hazy euphony (a promised orchestral version of the Sandman's song did not materialise).

Prokofiev’s First Suite from Cinderella, stitching together numbers from the ballet in different sequences, proved a surprisingly meaty centrepiece in this trilogy of fairytales. It veered from Petrenko’s giant symphonism at either end, the midnight waltz sweeping to a monster-clock catastrophe of an impact you’d never get in the theatre, to the impressionistic delicacy of the Fairy Godmother’s haunting music framed by the lazy days of the Summer Fairy and hell-for-leather incisiveness in the music of the Ugly Sisters.

The Liverpool audience seems to have a boundless enthusiasm and appreciation for what Petrenko and his players go flat out to give them in their handsomely-refurbished concert hall – another one for London to be envious of - and it provided what felt like an end-of-concert ovation for the Prokofiev music. But the highest pleasures were yet to come in the castle hall and courtiers of the Sleeping Beauty springing to life after a century.

Petrenko knew when to be taut but was physically relaxed enough to dance when the music is more relaxed. A very fast and vivacious march led into the most dazzing of all Tchaikovsky’s polonaises, presenting the fantasy characters who share their provenance with the protagonist in the fairytales of Charles Perrault. The animals offer some of the finest wind solos in the entire orchestral repertoire; both the ensembles and the individual melodies had a huge impact on Stravinsky and Prokofiev. What we now tend to know as the “Bluebird” sequence – actually a pas de quatre – touches Mozart in its simple sublime; principal flautist Cormac Henry and clarinettist Ben Mellefont dared more in their dovetailing and cadenzaing than any wind player on the many complete recordings of the ballet.

Oboist Jonathan Small, having played a mewling Puss in Boots (Bakst's design pictured left), came back as classical perfection personified in the great pas de deux, the second opportunity Petrenko took to underline Tchaikovsky the symphonist (the first was in the Intrada to the sequence for Florestan and his sisters, effortlessly classy in its string unisons, though there was some violin fudging in the waltz for Cinderella and her Prince, making a second appearance in the evening from a different perspective).

Oboist Jonathan Small, having played a mewling Puss in Boots (Bakst's design pictured left), came back as classical perfection personified in the great pas de deux, the second opportunity Petrenko took to underline Tchaikovsky the symphonist (the first was in the Intrada to the sequence for Florestan and his sisters, effortlessly classy in its string unisons, though there was some violin fudging in the waltz for Cinderella and her Prince, making a second appearance in the evening from a different perspective).

Petrenko got them to play the Sarabande, homage to Louis XIV, without vibrato, period-style, before springing the mazurka-ensemble, which can outstay its welcome, into vibrant life. Tempo contrasts here were just perfect, the surprise orgy running smack into the most resplendent brass fanfares imaginable – again, only possible in the concert hall like this – for the final ceremony on the old French tune "Vive Henri Quatre".

Pomp wasn’t having the last word. Bass clarinettist Marianne Rawles snuck on, and Ian Buckle, who’d made such elegant work of the piano flourishes which Tchaikovsky so surprisingy substitutes for the harp in his last act, took his place at the celesta for the most artistic and fresh-sounding of all Nutcracker Sugar Plum Fairies. Yes, this was a supreme vindication of Tchaikovsky’s staying power in dozens of tunes, countless colours, as the greatest 19th-century dance-master of them all.

Add comment