On the back wall of Birmingham Symphony Hall’s great oval space, two musicians are poised on a glass balcony that gives the illusion of not being there at all. A small square of warm light picks them out, vivid against the hall’s darkness. So framed, Saint-Saëns’ gentle Prière for cello and organ keeps its intimacy even in that large space, the two instruments blending into one equal sound that is clear, golden, and not too sweet.

The dancing promised us by the concert’s title was nowhere in evidence, but this opening nonetheless set the tone for the rest of the evening, which was characterised not only by striking use of light and darkness, but by religious works and clear, delicate sound textures. Organist Alexander Mason and cellist Andrew Skidmore were next joined on stage by mezzo soprano Martha McLorinan for Massenet’s 1893 Pie Jesu, another short, prayerful work, then Birmingham’s Ex Cathedra choir filled the stage for Aaron Copland’s In the Beginning (1947). Under Jeffrey Skidmore’s direction they lent incredibly clear diction to the biblical text, and the light, almost boyish tone in the sopranos confirmed the strong impression, set by the first two pieces, that this whole programme would be perfect for performance in a cathedral. I discovered later that, with the subsitution for Copland of Poulenc’s Litanies à la vierge noire, Ex Cathedra had in fact performed the same programme (which finishes with Duruflé's Requiem) with some of the same soloists in Worcester Cathedral in 2007.

Now, there’s absolutely nothing wrong with repeating something that works well – and this mostly French, mostly twentieth-century religious sequence works very well – but discovering the repetition confirmed that this concert had its origins in a disparate set of strong artistic visions. The programme notes reveal that David Massingham, one of directors of the International Dance Festival, and the Canadian choreographer Hélène Blackburn had wanted to try putting dance to organ music, and that Ex Cathedra’s Jeffrey Skidmore had suggested Duruflé’s Requiem (and presumably pulled the rest of the programme from his back catalogue). Meanwhile the Festival organisers had roped in some dancers from Birmingham Royal Ballet and young Kathak dance star Aakash Odedra to guest alongside the dancers from Blackburn’s company, Cas Public.

Now, there’s absolutely nothing wrong with repeating something that works well – and this mostly French, mostly twentieth-century religious sequence works very well – but discovering the repetition confirmed that this concert had its origins in a disparate set of strong artistic visions. The programme notes reveal that David Massingham, one of directors of the International Dance Festival, and the Canadian choreographer Hélène Blackburn had wanted to try putting dance to organ music, and that Ex Cathedra’s Jeffrey Skidmore had suggested Duruflé’s Requiem (and presumably pulled the rest of the programme from his back catalogue). Meanwhile the Festival organisers had roped in some dancers from Birmingham Royal Ballet and young Kathak dance star Aakash Odedra to guest alongside the dancers from Blackburn’s company, Cas Public.

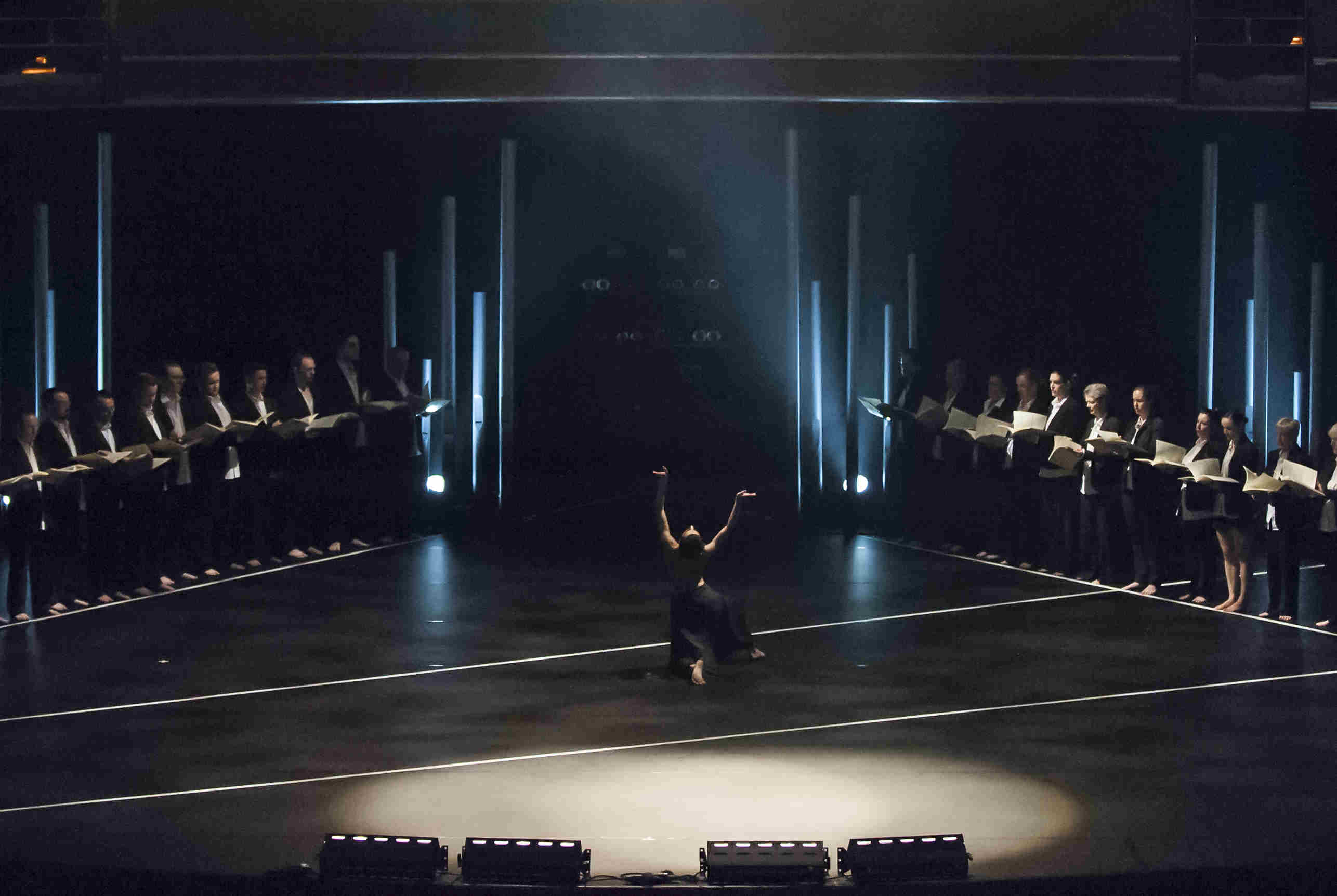

Choreographing across continents, and putting dance into a huge choral work, are both hard tasks, and in some ways the artists involved have risen tremendously to the challenge: Cas Public’s impressive dancers flicker with speed and precision through numerous fugue-like reiterations and inventive variations of a core sequence; Ex Cathedra’s singers ebb and flow on the stage to make way for the dancers without losing a thread of their sound; simple but astonishingly effective lighting gives the bare stage a visual richness, depth and texture to match the music.

But more is owed to a requiem than merely echoing its musical structure in movement: more even than other mass texts, a requiem addresses God with heart-rending immediacy, pleading for peace both for the departed and for us, who mourn them. Kenneth MacMillan’s setting of ballet to Fauré’s Requiem, after his friend John Cranko’s untimely death in 1973, is almost unbearably poignant precisely because it is imbued with the rawness of real loss. And whatever his own feelings about God, there is a clear sense in Duruflé’s Requiem of the peace, redemption and transcendence to be found through the liturgy of the Mass for the Dead.

But based as it is on twisty, almost violent partner work that throws women around in moves borrowed from acrobatic rock’n’roll, the core sequence of Blackburn’s choreography has nothing of a journey towards redemption; rather, the constant refrain is struggle, even during the anguished prayer of the Pie Jesu. Perhaps it’s meant to symbolise the struggle for faith or against death, but then why does it look so much like violence against women? This impression is particularly strong in the Introit, which the female dancers must perform in spectacularly tasteless black patent stiletto heels that, paired with their shorts, white shirts and black jackets, make them look like blank-faced strippers, and it never entirely disappears. It is not until the Sanctus that some sense of the sacred returns, through the beautiful arched back and flowing hands of Aakash Odedra’s luminous Kathak solo (pictured above right), and the Agnus Dei too is rendered both gentle and profound by Karla Doorbar and Max Maslen, guest dancers from Birmingham Royal Ballet, in an elegiac, beautiful pas de deux (pictured above left).

But based as it is on twisty, almost violent partner work that throws women around in moves borrowed from acrobatic rock’n’roll, the core sequence of Blackburn’s choreography has nothing of a journey towards redemption; rather, the constant refrain is struggle, even during the anguished prayer of the Pie Jesu. Perhaps it’s meant to symbolise the struggle for faith or against death, but then why does it look so much like violence against women? This impression is particularly strong in the Introit, which the female dancers must perform in spectacularly tasteless black patent stiletto heels that, paired with their shorts, white shirts and black jackets, make them look like blank-faced strippers, and it never entirely disappears. It is not until the Sanctus that some sense of the sacred returns, through the beautiful arched back and flowing hands of Aakash Odedra’s luminous Kathak solo (pictured above right), and the Agnus Dei too is rendered both gentle and profound by Karla Doorbar and Max Maslen, guest dancers from Birmingham Royal Ballet, in an elegiac, beautiful pas de deux (pictured above left).

The scale of the collaboration is impressive, its ambition laudable - and I was intrigued/impressed enough by all the artists on stage to want to see them again - but the broth at Symphony Hall on Friday was spoiled by too many cooks: this danced Duruflé is not a keeper.

- The International Dance Festival sees a wide range of dance events taking place across Birmingham until May 25.

Add comment