Sunday Book: Yiyun Li - Dear Friend, From My Life I Write to You in Your Life | reviews, news & interviews

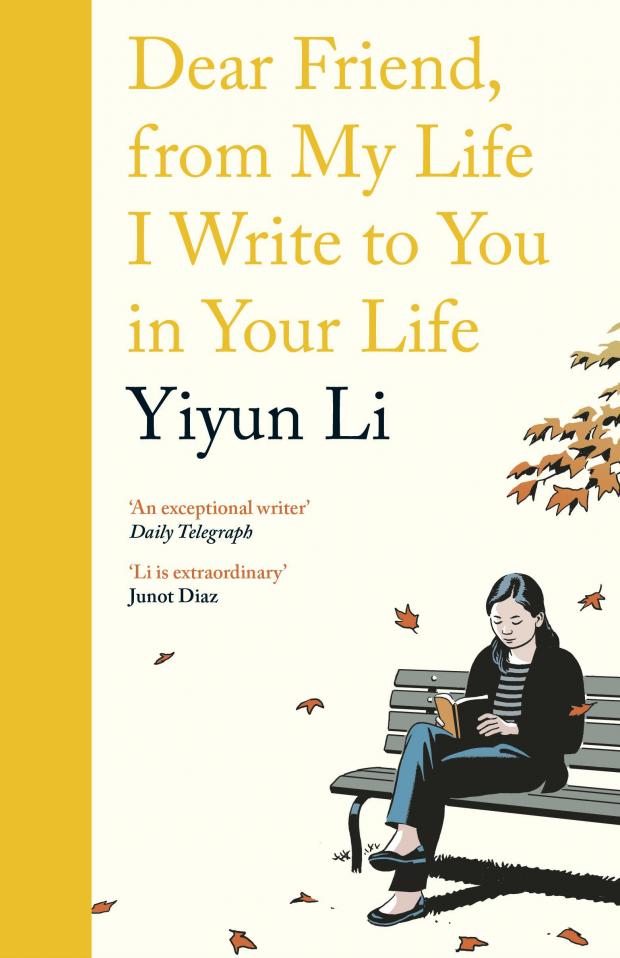

Sunday Book: Yiyun Li - Dear Friend, From My Life I Write to You in Your Life

Sunday Book: Yiyun Li - Dear Friend, From My Life I Write to You in Your Life

A brave meditation on depression and the consolations of literature

Yiyun Li’s fiction comes garlanded in praise from authors and journals that don’t ladle it out carelessly, so it feels almost churlish to cavil over a memoir written during the course of two years while the author battled serious mental health issues.

Dear Friend, From My Life I Write to You in Your Life – a quote from Katherine Mansfield’s personal journal – is not actually a memoir even in the most broad-brush sense of the term. Rather it’s a collection of essays – meditations one might call them – on depression and life and what makes it worth living. Reading this book you wonder, so don’t come here seeking balm for the soul. “Painful,” says the press release, and that’s true enough, but “richly affirming”? I’m not so sure.

I can’t decide: is Li’s book deep, or simply deeply pretentious. “I was reading Kierkegaard while waiting to pick up my children from school”, she writes at one point – and you want to shout: “Get a life, woman!” The line introduces a quote from Either/Or, the Danish philosopher’s first published work, in which he notes how, reading an epitaph, you are “easily led to wonder how it went with his life in the world; one would like to climb down in the grave to converse with him”. The quote refers back to the book’s title and the fact that Li reads in order to talk to other writers, to enter into discussion with them. She always reads with pen in hand, inscribing comments and questions in the margin, and has said that she frequently shouts at books the way many of us shout at the TV.

All the writers she admires (Turgenev, Elizabeth Bowen, Nabokov, John McGahern and William Trevor, whom she is eventually able to commune with in person, even though she writes that “a writer and a reader should never be allowed to meet”) seem to dwell on solitude and self-destruction. The book’s opening chapter is “Amongst People”, an homage (one must assume) to McGahern’s claustrophobic masterpiece Amongst Women.

All the writers she admires (Turgenev, Elizabeth Bowen, Nabokov, John McGahern and William Trevor, whom she is eventually able to commune with in person, even though she writes that “a writer and a reader should never be allowed to meet”) seem to dwell on solitude and self-destruction. The book’s opening chapter is “Amongst People”, an homage (one must assume) to McGahern’s claustrophobic masterpiece Amongst Women.

Li was born in Beijing amid the tumult of the Cultural Revolution and came to the US as a student, studying for a PhD in immunology. She never finished, becoming instead a writer and holds an MFA from the celebrated Iowa Writers’ Workshop plus an MFA in creative non-fiction from the University of Iowa. She’s been published in prestigious magazines, won numerous awards in both the US and Britain and has been translated into a score of languages. But not into Chinese, her native tongue and the language she renounced, dreaming, thinking, speaking and writing only in English.

Li also has a total aversion to the personal pronoun, which can make for some convoluted sentences. That’s partly linguistic (it doesn’t really exist in Chinese) but also, one must assume, psychological: “There is this emptiness in me. All the things in the world are not enough to drown out the voice of this emptiness that says: you are nothing.” If she rids herself of the emptiness, will she be “less than nothing”? Paradoxically, she seeks to “erase” herself by writing. “When I gave up science I had a blind confidence that in writing I could will myself into nonentity.”

Depression, even when not suicidal, as Li’s was, wrecks your regular thought process. It takes different forms, its outward sign often anger, but it makes you look relentlessly inward, inevitably finding much you don’t like and thus deepening the depression. Li has flashes of memory, and it’s how we learn her back story. Drafts of Dear Friend were written when life “began to feel unbearable. Composing a sentence is better than composing none; an hour taken away from treacherous rumination is an hour gained”.

She admits in an Afterword that “Coherence and consistency are not what I have been striving for” and one can understand why. For someone who wishes to erase herself this is a brave book though I think few people will truly be able to engage with it and fewer still will find comfort. What it lacks, I suspect, is a brave editor.

- Dear Friend, From My Life I Write to You in Your Life is published by Hamish Hamilton

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Add comment