The American poet-critic Randall Jarrell once entitled a collection of essays A Sad Heart at the Supermarket. He might have enjoyed Michel Houellebecq’s poem “Hypermarket - November”. Its forlorn narrator has “stumbled into freezer”, then “collapsed at the cheese counter” where “Two old ladies were carrying sardines./ The first turned to tell her neighbour,/ ‘It’s sad, all the same, for a boy that age’.” For well over than two decades, the veteran enfant terrible of French literature has been swooning in noisy revulsion at the decadence and emptiness of his godless consumer society. Should we feel pity, or respect, for the diehard disdain of “a boy that age”?

Even if you have not followed the incendiary trail of seven novels that began in 1994 with Extension du Domaine de la Lutte, Houellebecq’s poetry opens a revealing window into a stubbornly consistent career. His mischievous, trend-surfing satires and provocations - most recently, the dystopian fantasy of a France subject to Saudi-bankrolled Islamist rule in Submission - flow over deeply traditionalist currents of irony, elegy and nostalgia. “I am like a child who no longer has the right to tears,” one characteristic lyric begins. “Lead me to the country where the good people live.”

For almost 30 years, Houellebecq the poet has sought that country. His authorial progress began in verse, with a collection in 1992. Its title? The Pursuit of Happiness. Subtitled “a personal anthology”, this selection of 132 pieces appeared in French in 2014. The English edition arrives shorn of the preface by Agathe Novak-Lechevalier, and without any explanatory notes. Like Houellebecq, the austere presentation seems to bark, or lump him. However, it offers the huge bonus - for a reasonably-priced volume issued by a mainstream publisher - of parallel texts. The original French poem sits on the verso of each page, with Gavin Bowd’s translation opposite.

The volume groups work from different sources into the five acts of a kind of narrative, from the urban anomie of supermarkets, dole queues and hospital wards through the epiphanies of love, and the anguish of its loss, into glimpses of metaphysical transcendence, visions of solitude, and journeys through a blighted, accursed world. Readers who enjoy the dandyish despair of his fiction will not be shocked to find that, in poetry, Houellebecq channels masters such as Baudelaire - such a giant ghost here that he almost deserves a co-author’s credit - and Verlaine. In many pieces, he seems to take Baudelaire’s Parisian flâneur by the palsied hand and lead him through an even more disenchanted landscape of megastores and high-speed trains, computer screens and beach resorts where “The sun turned on the waters/ Between the edges of the pool/ Monday morning, new desires,/ A smell of urine floats in the air.”

New-wave dandyism aside, a pared-down but well-turned bleakness recalls Beckett in its view of suffering humankind as “A thing among things,/ A thing more fragile than things/ A very fragile thing/ Always waiting for love/ Love, or metamorphosis”. Given their erotic fervour only half-concealed by cynicism, admirers of the novels will not be startled by the irony-free romanticism of some love poems. A couple might even fit on greetings cards. Carla Bruni - aka Madame Sarkozy - has recorded a setting of the jewelled lyric proclaiming that “There exists, even in the midst of time,/ The possibility of an island”. But who knew that, in English, Houellebecq could sound so much like Philip Larkin - or even John Betjeman, when (for instance) “Sunday spread its slightly sickly veil/ On the chip-shops and the dive-bars”?

Houellebecq in verse often swings to a cheerless gallows humour. The misery can be hilarious. A sodden youth-hostelling break with his son in the Alps means that “I felt like ceasing to live… The rain falls more and more…. Soon my teeth will also fall,/ The worst is yet to come”. Yes, we’ve all stayed in hostels like that. Pessimism sniffs out such headquarters of ennui to corroborate its gloom: “I love hospitals, asylums of suffering/ here the forgotten old turn into organs/ Beneath the mocking and utterly indifferent eyes/ Of interns who scratch themselves, eating bananas.”

In French, that quatrain’s comic jolt depends on the bathetic rhyme of “organes” and “bananes”. The bilingual text (a cause for congratulation) has the downside that readers of French can inspect line-by-line the translator’s choices and tactics. In general, Bowd has sacrificed the highly traditional music of the verse - its cadences and assonances, above all its regular rhyme-schemes - for a clear report on the meaning of each line. True, when Bowd can find a handy English rhyme, he uses it, and he can match the oddly serene sway and roll of Houellebecq’s rhythms. Still, plain, prosaic sense predominates; unavoidable, probably, over 132 poems, but also a pity. Houellebecq’s retro-styled musicality voices a sort of Utopian yearning conspicuously at odds with his dominant notes of rancour, solitude and disillusion.

In French, that quatrain’s comic jolt depends on the bathetic rhyme of “organes” and “bananes”. The bilingual text (a cause for congratulation) has the downside that readers of French can inspect line-by-line the translator’s choices and tactics. In general, Bowd has sacrificed the highly traditional music of the verse - its cadences and assonances, above all its regular rhyme-schemes - for a clear report on the meaning of each line. True, when Bowd can find a handy English rhyme, he uses it, and he can match the oddly serene sway and roll of Houellebecq’s rhythms. Still, plain, prosaic sense predominates; unavoidable, probably, over 132 poems, but also a pity. Houellebecq’s retro-styled musicality voices a sort of Utopian yearning conspicuously at odds with his dominant notes of rancour, solitude and disillusion.

I wish that Bowd had sometimes let his translator’s hair down and taken some diabolical liberties with the old curmudgeon. Take the typical lyric that begins “Il n’y a pas d’amour/ (Pas vraiment, pas assez)/ Nous vivons sans secours,/ Nous mourrons délaissés.// L’appel à la pitié/ Résonne dans la vide/ Nos corps sont estropiés,/ Mais nos chairs sont avides.” Unsatisfied by Bowd’s, I tried my own, shameless, version: “Love does not exist/ Not deep, in the heart/ Beyond help, we persist/ Forsaken, we depart.// The plea for tears/ Falls on deaf ears/ Our bodies are bust/ But our flesh full of lust.” So much of the heft of Houellebecq’s poetry lies in its playful or wistful soundscape that this translation’s puritanical refusal of these charms muffles its force. Bowd’s rendering of the pastoral finale to “A Summer in Deuil-la-Barre” likewise left me wanting more. The original runs: “Un cloche tinte dans l’air serein/ Le ciel est chaud, on sert du vin,/ Le bruit du temps remplit la vie;/ C’est une fin d’après-midi”. Never mind Betjeman. This surely calls for the full-on Rupert Brooke; perhaps: “Through tranquil air, a church-bell’s chime;/ The sky is hot. We lift a glass./ Life fills up with the sound of time./ This afternoon has come to pass.” Thanks to the rare blessing of the parallel text, anyone with a little French can have a go. Chapeau bas, Heinemann.

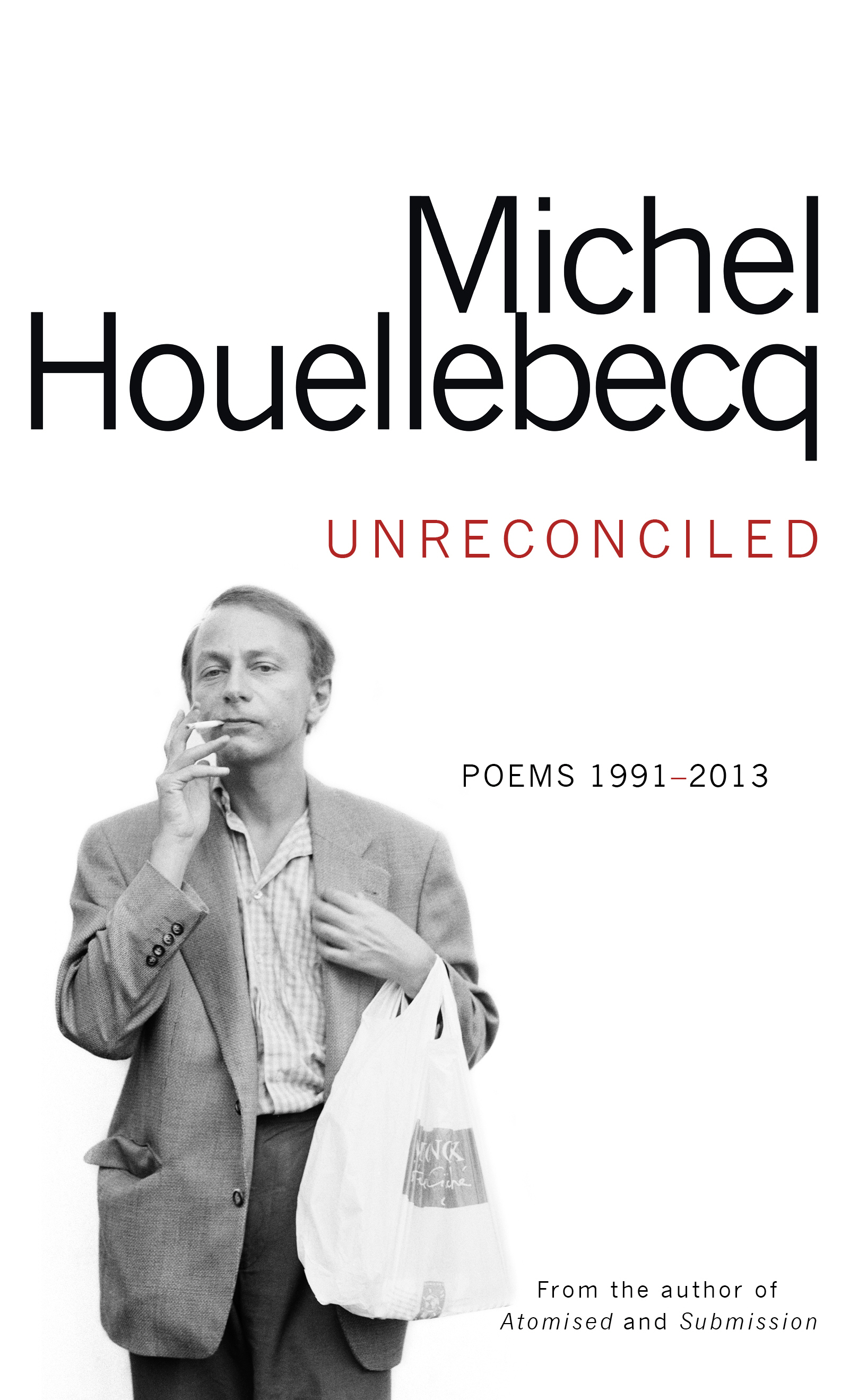

- Unreconciled: Poems 1991-2013 by Michel Houellebecq, translated by Gavin Bowd (Heinemann, £16.99)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment