Masha Karp: George Orwell and Russia review - dystopia's reality | reviews, news & interviews

Masha Karp: George Orwell and Russia review - dystopia's reality

Masha Karp: George Orwell and Russia review - dystopia's reality

An exploration of Orwell's unyielding critiques of dictatorship, and how the Soviet Union responded

The war in Ukraine, which Russia’s President Vladimir Putin insists on calling a “special military operation”, may have given fresh urgency to George Orwell’s warning in Nineteen Eighty-Four of the dangers of totalitarian newspeak.

Orwell was ever alert to propaganda but otherwise ignorant of Russian society and language. In the summer of 1948, the émigré publisher Vladimir Gorachek wrote in Russian to congratulate him on the achievement of Animal Farm, which a Kremlin-backed periodical Oktyabr had just denounced as “a virulently anti-Soviet lampoon”. When Orwell responded with incomprehension, Gorachek wrote back a second letter, this time in faulty English, apologising for his mistake: “We thought that such a perfect understanding of all the events that have unfolded in our country since the revolution, and of the very substance of the regime now established there, could not have been acquired without a knowledge of the Russian language.”

In fact, the Politburo was so wary of the novelist’s anti-Soviet message that Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four were not published officially in the USSR until 1988, and even then not in Moscow or Leningrad, or in book form, but serialised in a couple of obscure journals circulating in Latvia and Moldova respectively.

Orwell’s understanding of Stalinism was hardly perfect – unlike his American contemporary John Steinbeck, he had never actually set foot inside the USSR – but to many Russians it did seem miraculous. In George Orwell and Russia, Karp sets out to explain the miracle, how it was that the Englishman saw through “a huge system of organised lying” from afar while Steinbeck merely took it at face value in his folksy 1948 travelogue, Journey to Russia.

Orwell’s criticism of the Soviet Union was shaped by his experiences in the Spanish Civil War. In December 1936, arriving in Barcelona, a city run by anarchists, he was uplifted by the camaraderie at large. But within six months, seeing first-hand “the civil war within the civil war”, i.e. among the different left-wing factions, and in particular the way the Stalinist NKVD pitted Republican troops against the anarchists and the Trotskyite Workers Party of Marxist Unification (POUM), turned Orwell firmly against the regime in Moscow.

Orwell’s criticism of the Soviet Union was shaped by his experiences in the Spanish Civil War. In December 1936, arriving in Barcelona, a city run by anarchists, he was uplifted by the camaraderie at large. But within six months, seeing first-hand “the civil war within the civil war”, i.e. among the different left-wing factions, and in particular the way the Stalinist NKVD pitted Republican troops against the anarchists and the Trotskyite Workers Party of Marxist Unification (POUM), turned Orwell firmly against the regime in Moscow.

Having come to Spain to fight for the Republican government against fascists, he found himself, in May 1937, defending POUM headquarters from attack by government forces owing to a campaign of misinformation masterminded by the NKVD’s leader in Spain, Alexander Orlov – a sinister prototype for O’Brien in Ninety Eighty-Four – who had forged some “very interesting documents proving the connection of the Spanish Trotskyists with Franco”.

In Homage to Catalonia, Orwell described the period as “one of the most unbearable of my whole life. I think few experiences could be more sickening, more disillusioning, or, finally, more nerve-racking than those evil days of street-fighting.”

Upon returning to Britain and writing about his experiences, Orwell was criticised for attacking the Soviet Union, especially during World War Two. Both the public and intelligentsia credited Stalin with helping to defeat the Nazis. In 1944, he began work on Animal Farm and finished the novel in only three months. Yet he was unable to find a publisher for over a year, and even then, the publisher in question, Fredric Warburg, revealed years later that his own wife had threatened to divorce him if he published Orwell's satire because she could not bear the thought of ingratitude towards the Russians.

The truth is, as Karp shows, that Orwell was opposed to dictatorships of all kinds, left and right, and his anti-authoritarianism has as much relevance in today’s post-truth society in the West as it does in Russia or Ukraine or anywhere else. It’s a timely and well-researched account of the origins of newspeak.

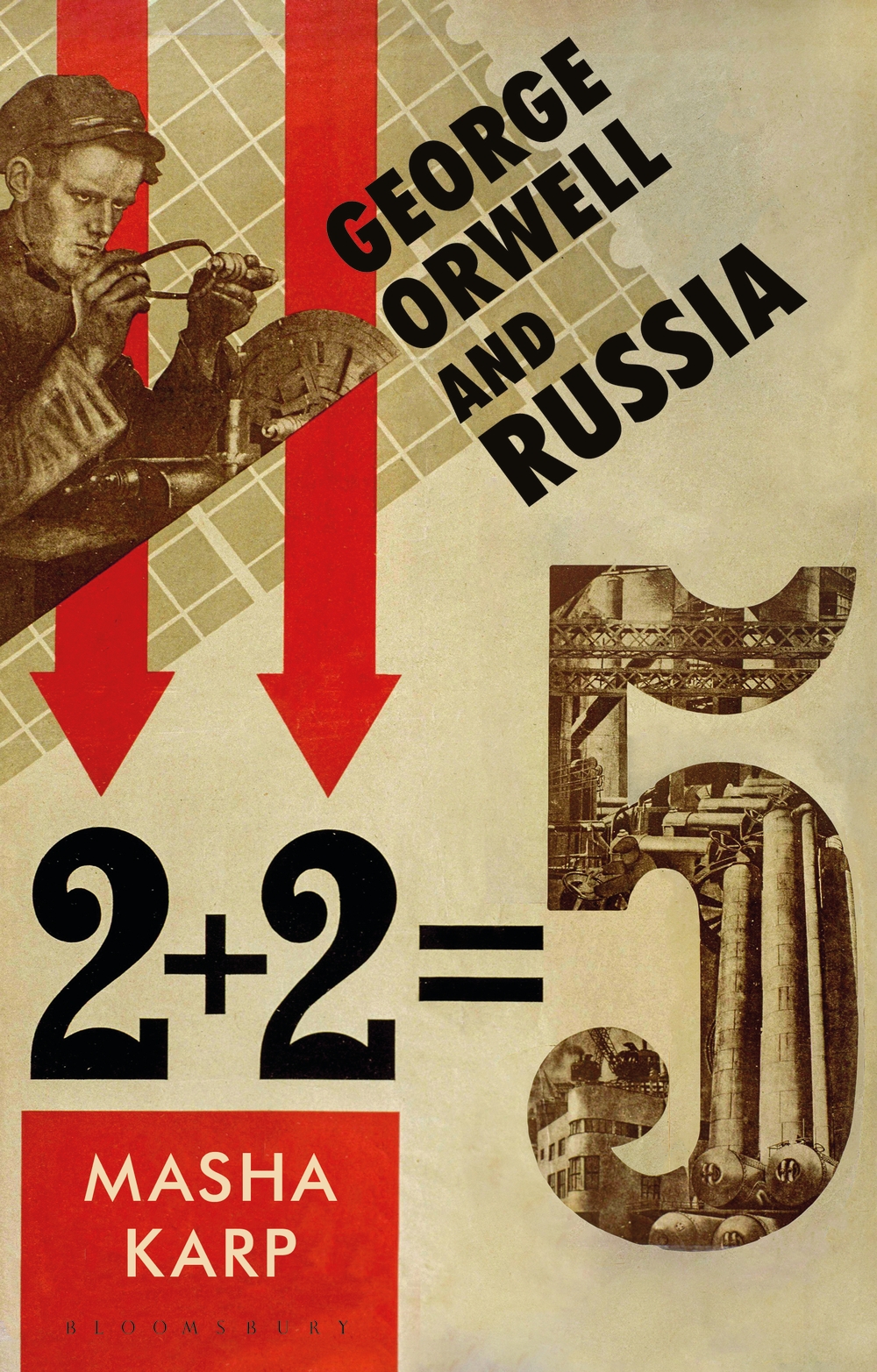

- George Orwell and Russia, by Masha Karp (Bloomsbury Academic, £21.99)

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

more Books

Jonn Elledge: A History of the World in 47 Borders review - a view from the boundaries

Enjoyable journey through the byways of how lines on maps have shaped the modern world

Jonn Elledge: A History of the World in 47 Borders review - a view from the boundaries

Enjoyable journey through the byways of how lines on maps have shaped the modern world

Lisa Kaltenegger: Alien Earths review - a whole new world

Kaltenegger's traverses space in her thoughtful exploration of the search for life among the stars

Lisa Kaltenegger: Alien Earths review - a whole new world

Kaltenegger's traverses space in her thoughtful exploration of the search for life among the stars

Heather McCalden: The Observable Universe review - reflections from a damaged life

An artist pens a genre-spanning work of tender inconclusiveness

Heather McCalden: The Observable Universe review - reflections from a damaged life

An artist pens a genre-spanning work of tender inconclusiveness

Dorian Lynskey: Everything Must Go review - it's the end of the world as we know it

Authoritative account of how the apocalypse has always been just around the corner

Dorian Lynskey: Everything Must Go review - it's the end of the world as we know it

Authoritative account of how the apocalypse has always been just around the corner

Andrew O'Hagan: Caledonian Road review - London's Dickensian return

Grotesque and insightful, O’Hagan’s broad cast of characters illuminates a city’s iniquities

Andrew O'Hagan: Caledonian Road review - London's Dickensian return

Grotesque and insightful, O’Hagan’s broad cast of characters illuminates a city’s iniquities

Annie Jacobsen: Nuclear War: A Scenario review - on the inconceivable

Brimming with terrifying facts and figures, but struggling with an immeasurable subject

Annie Jacobsen: Nuclear War: A Scenario review - on the inconceivable

Brimming with terrifying facts and figures, but struggling with an immeasurable subject

Anna Reid: A Nasty Little War - The West's Fight to Reverse the Russian Revolution review - home truths

Reid brings to light a war the West has tried its best to forget

Anna Reid: A Nasty Little War - The West's Fight to Reverse the Russian Revolution review - home truths

Reid brings to light a war the West has tried its best to forget

Tom Chatfield: Wise Animals review - on the changing world

A compelling account of how we use technology – and how it uses us

Tom Chatfield: Wise Animals review - on the changing world

A compelling account of how we use technology – and how it uses us

Sheila Heti: Alphabetical Diaries review - an A-Z of inner life

Heti goes far beyond a gimmick in this work of surprising and moving insight

Sheila Heti: Alphabetical Diaries review - an A-Z of inner life

Heti goes far beyond a gimmick in this work of surprising and moving insight

David Harsent: Skin review - our strange surfaces

A fine poet pens a set of resilient expressions and elegant introspections

David Harsent: Skin review - our strange surfaces

A fine poet pens a set of resilient expressions and elegant introspections

Brian Klaas: Fluke review - why things happen, and can we stop them?

Sweeping account of how we control nothing but influence everything

Brian Klaas: Fluke review - why things happen, and can we stop them?

Sweeping account of how we control nothing but influence everything

Richard Schoch: Shakespeare's House review - nothing ill in such a temple

Scholar makes the Bard's house a home in his history of dramatic domesticity

Richard Schoch: Shakespeare's House review - nothing ill in such a temple

Scholar makes the Bard's house a home in his history of dramatic domesticity

Add comment