Jenny Uglow: Mr Lear - A Life of Art and Nonsense review - a lonely Victorian life, so richly illustrated | reviews, news & interviews

Jenny Uglow: Mr Lear - A Life of Art and Nonsense review - a lonely Victorian life, so richly illustrated

Jenny Uglow: Mr Lear - A Life of Art and Nonsense review - a lonely Victorian life, so richly illustrated

Emotional truths and visual virtuosity in a new biography of the 'dirty landscape-painter who hated his nose'

Jenny Uglow’s biography of Edward Lear (1812-1888) is a meander, almost day by day, through the long and immensely energetic life of a polymath artist.

These Victorians, tireless travellers, left behind such copious piles of paper that they can practically write their own biographies (at least in terms of external events). But it is Uglow’s gift to shape this mass of material into comprehensible narrative. Her authorial skill is complemented by the unusually attractive design of the book itself, with copious illustrations incorporated into the relevant pages.

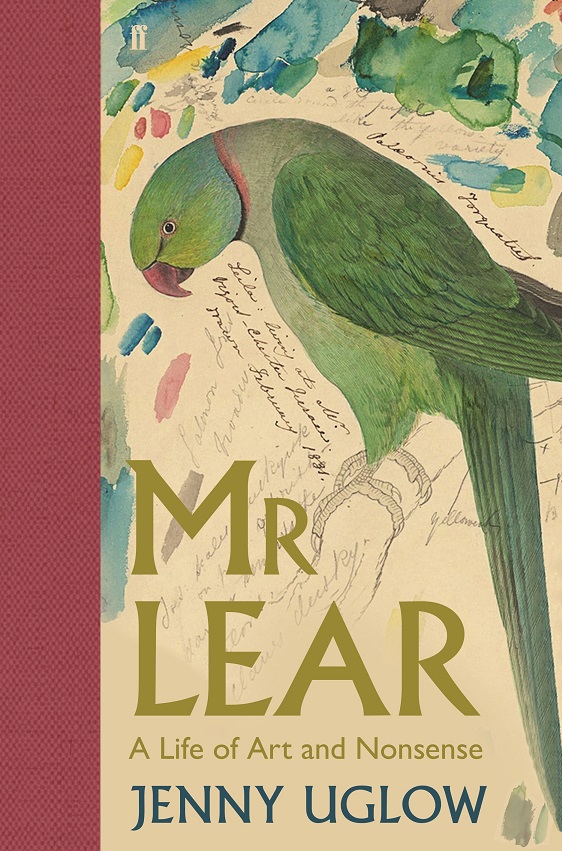

Lear’s nonsense verse and poetry, from The Owl and the Pussycat to his countless limericks, created a form that is not only lasting but much parodied; it was not as acknowledged in his own lifetime – although much enjoyed – as his marvellously accurate yet somehow poetic drawings of animals, notably birds, and especially parrots, and his landscape art, undertaken when his eyesight had declined, handicapping his close observation of the animal world. He was also a very accomplished musician, setting Tennyson’s poetry to music, and a welcome guest with networks of acquaintances and friends across Britain and Europe.

Lear’s nonsense verse and poetry, from The Owl and the Pussycat to his countless limericks, created a form that is not only lasting but much parodied; it was not as acknowledged in his own lifetime – although much enjoyed – as his marvellously accurate yet somehow poetic drawings of animals, notably birds, and especially parrots, and his landscape art, undertaken when his eyesight had declined, handicapping his close observation of the animal world. He was also a very accomplished musician, setting Tennyson’s poetry to music, and a welcome guest with networks of acquaintances and friends across Britain and Europe.

Even so it has been only in recent decades, in the flurry round the centenary of his death, with the pioneering research and publications of Vivian Noakes (who also masterminded the revelatory 1985 Royal Academy exhibition), that he has come fully into his own as the genius he was. Perhaps only in the late 20th century has his art begun to be so widely appreciated, as part of a growing understanding of historic English art of the period as a whole.

Uglow’s own trajectory has embraced not only biographies of individuals, but also the context in which they lived and worked. She is an outstanding chronicler of major minor masters – or minor major masters depending on how you categorise them. She looks to the comparatively overlooked (in our time, rather than theirs) just beyond the mainstream, to illuminate the richness beyond, and has given us the biographies of Mrs Gaskell, of Hogarth, of Thomas Bewick the engraver, as well as vividly describing such collectives as the scientists of Birmingham, the “Lunar Men”, who happened to change how we looked at the world, and subjects such as how the English population fared during the Napoleonic wars. She is a social historian as well as a biographer.

Her gift is to ornament, to dazzle, to entice, all with vivid detail. And thus with Lear, the artist and poet who hid his melancholy perhaps even from himself with wit and humour, as well as excelling in that peculiarly English art, the evocative, suggestive, skilled watercolour, of landscape, and the vivid imagery of travel art.

No one knows how many children Lear’s mother had – between 17 and 21 – and Edward was the last but one to survive to maturity; he was both epileptic and severely short-sighted, ignored by his mother and more or less brought up by his much older sister Ann. In later years Lear met Ann only rarely, but they corresponded. His family’s fortunes were varied, and Lear began in adolescence to support himself by selling his art at inns and staging posts. Money was often a concern, and later he sought patronage and subscriptions to finance his numerous publications.

Lear was hardly trained as an artist, a lack he felt keenly; he was happiest painting on his travels, and could be fretful in the studio

If “National Treasure” status could be awarded posthumously, he would be in the pantheon. As it was, this complicated man, in spite of a huge network of friends and patrons – from the upper middle classes to the aristocracy – was profoundly lonely. His isolation from England was self-imposed (for his health), although he returned often; when he died in San Remo only his doctor, his doctor’s wife, and his loyal servant attended.

Lear was hardly trained as an artist, a lack he felt keenly; he was happiest painting on his travels, and could be fretful in the studio. As a young man he was attached to the London Zoological Society and became a superb and accurate depicter of animals, and famously an extraordinary interpreter of avian life. But he was drawn to landscape, too: on his travels through Europe and beyond – to the Middle East, Egypt and India – he described in vivid prose as well as image what he saw and felt. His life was replete with contradictions: fully aware of class, saddened by his lack of a classical education, he gave at royal request a dozen drawing lessons to Queen Victoria.

Depressed, unrequitedly in love with a younger man, Frank Lushington – who after overseas colonial appointments led a lawyerly English pater familias life – Lear was subtly the epitome not of the tragic but of the melancholic clown. Friend to the Tennysons, an outsider perhaps like them, and repressed sexually (although there had been a sexually transmitted disease in his youth), he did improbably think of marriage and almost proposed to a woman decades younger than himself. But his constant companion for nearly three decades – perhaps his closest relationship – was his devoted servant, Giorgio, an Albanian Christian, and his beloved cat, Foss; then, for the few years after Giorgio’s death, Giorgio’s son.

Uglow’s substantial publication mirrors all these contradictions in mesmerising detail. What is somehow missing, though, is “Why?” Just what impelled him? Was all this energy, this creativity, an escape from inescapable isolation? How, in spite of his sadness, his depression, his physical ill health, did he keep going in such an amazing fashion? His work is accessible – although his limericks are surprisingly complex – and increasingly fodder for the psychologists (Adam Phillips has written brilliantly on him).

Jenny Uglow often rises to their subtle challenge. This is a dazzling, glittering book – but one with a curious hollow at its heart, perhaps like Lear himself.

- Mr Lear - A Life of Art and Nonsense by Jenny Uglow (Faber & Faber, £25)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Share this article

more Books

Jonn Elledge: A History of the World in 47 Borders review - a view from the boundaries

Enjoyable journey through the byways of how lines on maps have shaped the modern world

Jonn Elledge: A History of the World in 47 Borders review - a view from the boundaries

Enjoyable journey through the byways of how lines on maps have shaped the modern world

Lisa Kaltenegger: Alien Earths review - a whole new world

Kaltenegger's traverses space in her thoughtful exploration of the search for life among the stars

Lisa Kaltenegger: Alien Earths review - a whole new world

Kaltenegger's traverses space in her thoughtful exploration of the search for life among the stars

Heather McCalden: The Observable Universe review - reflections from a damaged life

An artist pens a genre-spanning work of tender inconclusiveness

Heather McCalden: The Observable Universe review - reflections from a damaged life

An artist pens a genre-spanning work of tender inconclusiveness

Dorian Lynskey: Everything Must Go review - it's the end of the world as we know it

Authoritative account of how the apocalypse has always been just around the corner

Dorian Lynskey: Everything Must Go review - it's the end of the world as we know it

Authoritative account of how the apocalypse has always been just around the corner

Andrew O'Hagan: Caledonian Road review - London's Dickensian return

Grotesque and insightful, O’Hagan’s broad cast of characters illuminates a city’s iniquities

Andrew O'Hagan: Caledonian Road review - London's Dickensian return

Grotesque and insightful, O’Hagan’s broad cast of characters illuminates a city’s iniquities

Annie Jacobsen: Nuclear War: A Scenario review - on the inconceivable

Brimming with terrifying facts and figures, but struggling with an immeasurable subject

Annie Jacobsen: Nuclear War: A Scenario review - on the inconceivable

Brimming with terrifying facts and figures, but struggling with an immeasurable subject

Anna Reid: A Nasty Little War - The West's Fight to Reverse the Russian Revolution review - home truths

Reid brings to light a war the West has tried its best to forget

Anna Reid: A Nasty Little War - The West's Fight to Reverse the Russian Revolution review - home truths

Reid brings to light a war the West has tried its best to forget

Tom Chatfield: Wise Animals review - on the changing world

A compelling account of how we use technology – and how it uses us

Tom Chatfield: Wise Animals review - on the changing world

A compelling account of how we use technology – and how it uses us

Sheila Heti: Alphabetical Diaries review - an A-Z of inner life

Heti goes far beyond a gimmick in this work of surprising and moving insight

Sheila Heti: Alphabetical Diaries review - an A-Z of inner life

Heti goes far beyond a gimmick in this work of surprising and moving insight

David Harsent: Skin review - our strange surfaces

A fine poet pens a set of resilient expressions and elegant introspections

David Harsent: Skin review - our strange surfaces

A fine poet pens a set of resilient expressions and elegant introspections

Brian Klaas: Fluke review - why things happen, and can we stop them?

Sweeping account of how we control nothing but influence everything

Brian Klaas: Fluke review - why things happen, and can we stop them?

Sweeping account of how we control nothing but influence everything

Richard Schoch: Shakespeare's House review - nothing ill in such a temple

Scholar makes the Bard's house a home in his history of dramatic domesticity

Richard Schoch: Shakespeare's House review - nothing ill in such a temple

Scholar makes the Bard's house a home in his history of dramatic domesticity

Add comment