World War Two: 1945 and the Wheelchair President, BBC Four | reviews, news & interviews

World War Two: 1945 and the Wheelchair President, BBC Four

World War Two: 1945 and the Wheelchair President, BBC Four

The four-term President who battled disability to steer the American war effort

More than an hour and a half, and not a moment too long: this moving and enlightening visual essay was a near-perfect example of broad brush modern history, enlivened by telling detail. It was a curiously intense history, written and narrated by a leading historian of the world wars of the 20th century, Professor David Reynolds, and predicated on the telling assumption that politics may be personal, and the personal may be political.

The underlying motif was the personality, in terms of physical health and psychological complexity, of that skilled and idealistic politician, Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882-1945). FDR was elected President of the United States for an unprecedented four terms (1932, 1936, 1940, 1944), and was the architect of the New Deal in the Depression, America’s involvement in World War Two, and – posthumously – the founding of the United Nations. His premature death, hastened by a history of extraordinarily botched medical care, terminated his democratic reign as the most powerful man in the world.

Roosevelt was perhaps the most reviled President in American history, but he was also adoredThe patrician Roosevelt, the only child of a fearsome widowed mother, was born with every advantage on offer for the rich, brilliantly well connected and educated. But David Reynolds vividly portrayed the two underlying tragedies in his life. His marriage to his fifth cousin once removed, the redoubtable and energetic Eleanor Roosevelt (niece of the other Roosevelt President, Teddy) was strained almost to breaking point by his affair with his secretary Lucy Mercer in 1920.

And FDR, struck down by polio in 1921, was effectively a paraplegic for the rest of his life, with his condition known only to a small circle. He never really walked again, only standing with the help of painful steel leg braces and corset, and needed help for every aspect of daily life including getting in and out of bed and going to the toilet. His courage was staggering, as was the complicity of his inside circle and journalists who kept his disability secret from the public. Rather than being seen in a wheelchair, he had wheels put on ordinary wooden chairs. Moreover his heart became seriously weakened, his blood pressure was sky high, and he was a heavy smoker and a drinker.

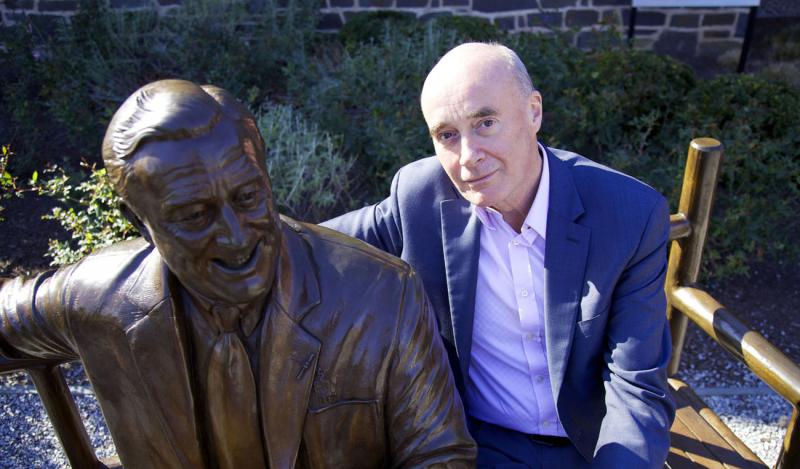

The narrative smoothly mixed vintage and documentary film and photography with radio broadcasts. There was the exuberance of political conventions, grim film clips from the Pacific and European theatres of war, and the quiet explication of the Manhattan Project and the atomic bomb. These were punctuated with the narrator’s autumnal excursions to FDR's estate, Springwood, in Hyde Park, 70 miles outside New York City, and we visited the Little White House in Warm Springs, Georgia, where he died on 12 April 1945.

The narrative smoothly mixed vintage and documentary film and photography with radio broadcasts. There was the exuberance of political conventions, grim film clips from the Pacific and European theatres of war, and the quiet explication of the Manhattan Project and the atomic bomb. These were punctuated with the narrator’s autumnal excursions to FDR's estate, Springwood, in Hyde Park, 70 miles outside New York City, and we visited the Little White House in Warm Springs, Georgia, where he died on 12 April 1945.

Roosevelt was perhaps the most reviled President in American history, loathed by isolationists and the Republican right wing, who curiously we were not shown. But he was also adored, and what we did see was the extraordinary and spontaneous outpouring of national grief as thousands of ordinary people, many openly weeping, lined the railway tracks to salute the train bearing the President back to Washington, and then on to his burial in the simple cemetery in Hyde Park.

Throughout his political life, his ideal had been the example of Woodrow Wilson (whose debilitating stroke had also been kept secret) and the League of Nations. We revisited the historic meetings between Stalin, Churchill and Roosevelt (pictured above at Tehran in 1943) and were shown with great clarity how Roosevelt’s ideals, for good and ill, meant that he compromised at the Yalta conference. As a consequence Eastern Europe (and particularly Poland) was sacrificed to pacify Stalin. That 14,000 mile round trip delivered the final blow to FDR’s health. He had to sit – and apologised to the Senate for sitting – for his mesmerising report to Congress after Yalta.

Throughout his political life, his ideal had been the example of Woodrow Wilson (whose debilitating stroke had also been kept secret) and the League of Nations. We revisited the historic meetings between Stalin, Churchill and Roosevelt (pictured above at Tehran in 1943) and were shown with great clarity how Roosevelt’s ideals, for good and ill, meant that he compromised at the Yalta conference. As a consequence Eastern Europe (and particularly Poland) was sacrificed to pacify Stalin. That 14,000 mile round trip delivered the final blow to FDR’s health. He had to sit – and apologised to the Senate for sitting – for his mesmerising report to Congress after Yalta.

The underlying thesis, persuasively presented, was that Roosevelt’s increasing frailty was a major factor in the complex negotiations at the end of the war and the tainted peace that followed. Yet we were properly encouraged to admire his idealism, his suffering, his great rhetorical gifts – "we have nothing to fear but fear itself" – and his superhuman achievements. His view of Stalin – that he could be brought into the Western fold, and indeed the Russians did join the UN – prevailed over Churchill’s passionate anti-Communist stance and determination to be firm. And as Reynolds eloquently explained, these events formed one of the great what-ifs of world history, with consequences still with us now.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

theartsdesk Q&A: Soft Cell

Upon the untimely passing of Dave Ball we revisit our September 2018 Soft Cell interview

theartsdesk Q&A: Soft Cell

Upon the untimely passing of Dave Ball we revisit our September 2018 Soft Cell interview

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

Demi Lovato's ninth album, 'It's Not That Deep', goes for a frolic on the dancefloor

US pop icon's latest is full of unpretentious pop-club bangers

Demi Lovato's ninth album, 'It's Not That Deep', goes for a frolic on the dancefloor

US pop icon's latest is full of unpretentious pop-club bangers

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Add comment