Poetry has always inspired artists. Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Dante’s Divine Comedy are two of the most enduring. And according to Art Everywhere, of which I will say little here but have written about elsewhere (see sidebar), the nation’s favourite painting is inspired by a more recent poem: JW Waterhouse’s The Lady of Shalott shows the ill-fated heroine of Tennyson’s famous verse moving inexorably towards her watery death “like some bold seer in a trance”. The second favourite is, incidentally, another narrative illustration of an ill-fated heroine on the point of meeting her watery fate – Millais’s Ophelia.

The Victorian era was the last big hurrah of literature-inspired visual works of art, and it was decidedly gothic in flavour. But the 20th century saw the death of narrative painting, and illustrations from myth and literature dropped out of fashion.

Painters were still influenced by literature, of course, but the influence, with a few notable exceptions, played out in more abstract, nebulous ways. Instead, we find a decisive switch – it’s writers who turn increasingly to the works of painters and sculptors. Poets looked to the historical canon – I haven’t included it here, but surely Larkin’s An Arundel Tomb is the greatest post-war poem to be inspired by a single work of art. But more often Modernist poets, particularly in America, looked to Modernist artists for inspiration.

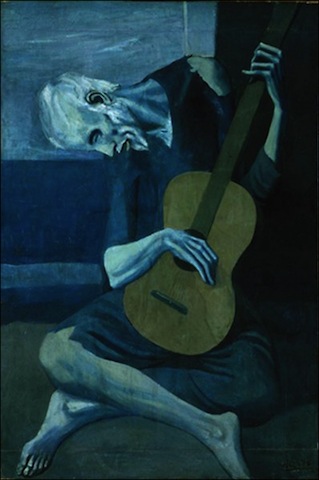

The conservative Larkin was no fan of Modernism, seeing ugliness and destruction in its methods. Yet for many other writers, Modernism in the visual arts appeared regenerative in its violence to form. Like visual artists of the 20th century, writers were no longer portraying a window on to the world as it had appeared since the Renaissance, but obviously filtered and changed by the imagination in startling ways. To quote Wallace Stevens (no.4), responding to Picasso’s The Old Guitarist, “Things as they are / Are changed upon the blue guitar.”

Below, responding to old and modern paintings, I’ve chosen nine 20th-century poems and one 21st-century one. The poems are illustrated by the paintings that directly inspired their thoughts.

Mourning Picture (main picture), Edwin Romanzo Elmer, 1890

The little-known American artist Edwin Ramanzo Elmer painted this strange and arresting work after the death from appendicitis of his 9-year-old daughter Effie. Here she is portrayed with her pet lamb and kitten, against the clapboard house her father built in Western Massachusetts. The remote and rigid figures of the artist and his wife appear in mourning clothes, though the painting was only given its title decades later, and not by the artist. The narrative voice in Adrienne Rich’s poem belongs to the dead Effie, the couple’s only child. Hauntingly, she compares the veins of the lilac leaf to her father’s “grief-tranced hand”.

1. Mourning Picture, Adrienne Rich (1965)

They have carried the mahogany chair and the cane rocker

out under the lilac bush,

and my father and mother darkly sit there, in black clothes.

Our clapboard house stands fast on its hill,

my doll lies in her wicker pram

gazing at western Massachusetts.

This was our world.

I could remake each shaft of grass

feeling its rasp on my fingers,

draw out the map of every lilac leaf

or the net of veins on my father's

grief-tranced hand.

Out of my head, half-bursting,

still filling, the dream condenses--

shadows, crystals, ceilings, meadows, globes of dew.

Under the dull green of the lilacs, out in the light

carving each spoke of the pram, the turned porch-pillars,

under high early-summer clouds,

I am Effie, visible and invisible,

remembering and remembered.

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1558

It takes a while for us to spot the pale legs kicking in the green sea to the right of the picture, since Bruegel’s great painting shows the fall of Icarus as an incidental occurrance, not the main event of this scene. But the insignificance of human suffering to the universe is indeed its theme. The plowman carries on with his task, while the “expensive, delicate ship”, after no doubt witnessing the incident, had “somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.” The Imagist poet William Carlos Williams was also inspired to write a poem about this painting, as well as another famous Bruegel work included here (see no.3).

2. Musée des Beaux Arts, W. H. Auden (1938)

About suffering they were never wrong,

The Old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position; how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along;

How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waiting

For the miraculous birth, there always must be

Children who did not specially want it to happen, skating

On a pond at the edge of the wood:

They never forgot

That even the dreadful martyrdom must run its course

Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot

Where the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer's horse

Scratches its innocent behind on a tree.

In Brueghel's Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the plowman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water; and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

Hunters in the Snow, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1565

Bruegel’s breathtaking panoramic painting shows a scene set in harshest winter. The weary hunters of the title are returning home at the end of a disappointing hunt (the rewards of their labours, as we see, are meagre, and even the dogs look a little sorry for themselves, though the expansive view they and we are looking down on is spectacular and uplifting). The scene is described with striking spareness, the poet picking out details that make up the composition as a whole, making us aware of "Bruegel the painter" bringing these elements carefully and strikingly together.

3. Hunters in the Snow, William Carlos Williams (1962)

The over-all picture is winter

icy mountains

in the background the return

from the hunt it is toward evening

from the left

sturdy hunters lead in

their pack the inn-sign

hanging from a

broken hinge is a stag a crucifix

between his antlers the cold

inn yard is

deserted but for a huge bonfire

that flares wind-driven tended by

women who cluster

about it to the right beyond

the hill is a pattern of skaters

Brueghel the painter

concerned with it all has chosen

a winter-struck bush for his

foreground to

complete the picture

The Old Guitarist, Picasso, 1903

Below are the first four cantos of a poem that extends by a further 29. Stevens’ rigorous and brilliant poem ponders the nature of reality and the quest of artists to profoundly alter it. “Things as they are / Are changed upon the blue guitar,” we are told in the first canto, and the refrain “things as they are” echoes like a recurring motif in a piece of music. Stevens was hugely influenced by the work of Modernist artists who flattened and fragmented pictorial space. His blue guitarist is a “shearsman of sorts”.

4. The Man with the Blue Guitar, Wallace Stevens (1937)

I

The man bent over his guitar,

A shearsman of sorts. The day was green.

They said, “You have a blue guitar,

You do not play things as they are.”

The man replied, “Things as they are

Are changed upon the blue guitar.”

And they said then, “But play, you must,

A tune beyond us, yet ourselves,

A tune upon the blue guitar

Of things exactly as they are.”

II

I cannot bring a world quite round,

Although I patch it as I can.

I sing a hero’s head, large eye

And bearded bronze, but not a man,

Although I patch him as I can

And reach through him almost to man.

If to serenade almost to man

Is to miss, by that, things as they are,

Say that it is the serenade

Of a man that plays a blue guitar.

III

Ah, but to play man number one,

To drive the dagger in his heart,

To lay his brain upon the board

And pick the acrid colors out,

To nail his thought across the door,

Its wings spread wide to rain and snow,

To strike his living hi and ho,

To tick it, tock it, turn it true,

To bang if form a savage blue,

Jangling the metal of the strings…

IV

So that’s life, then: things as they are?

It picks its way on the blue guitar.

A million people on one string?

And all their manner in the thing

And all their manner, right and wrong,

And all their manner, weak and strong?

The feelings crazily, craftily call,

Like a buzzing of flies in the autumn air,

And that’s life, then: things as they are,

This bussing of the blue guitar.

Self-Portrait at the Age of 63, Rembrandt, 1669

Many of Elizabeth Jennings’s poems are direct responses to paintings; you could take your pick from a prolific pool that takes us from Mantegna to Mondrian. Here she speaks of the searing and unflattering honesty of Rembrandt’s late self-portraits – “Your brush's care / Runs with self-knowledge” – which, through the unflinching depiction of nature’s cruel changes, help divest us “of fear of death.”

5. Rembrandt's Late Self-Portraits, Elizabeth Jennings (1975)

You are confronted with yourself. Each year

The pouches fill, the skin is uglier.

You give it all unflinchingly. You stare

Into yourself, beyond. Your brush's care

Runs with self-knowledge. Here

Is a humility at one with craft.

There is no arrogance. Pride is apart

From this self-scrutiny. You make light drift

The way you want. Your face is bruised and hurt

But there is still love left.

Love of the art and others. To the last

Experiment went on. You stared beyond

Your age, the times. You also plucked the past

And tempered it. Self-portraits understand,

And old age can divest,

With truthful changes, us of fear of death.

Look, a new anguish. There, the bloated nose,

The sadness and the joy. To paint's to breathe,

And all the darknesses are dared. You chose

What each must reckon with.

Continued overleaf: Anne Sexton, Sylvia Plath, X.J Kennedy, Allen Ginsberg and George Szirtes

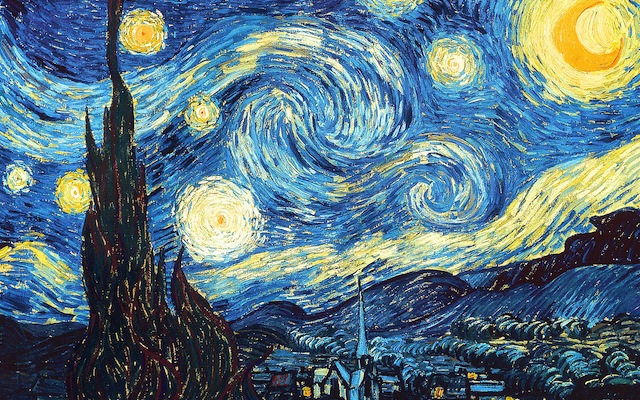

The Starry Night, Van Gogh, 1889

Van Gogh’s painting conveys both a sense of furious motion and an atmosphere of serenity: stars radiate in a turbulent sky, yet the town below, whose existence Sexton negates in the first line, appears calm and empty. Sexton, who committed suicide in 1974, longs for the oblivion of death, as if death were but to disappear “into that rushing beast of night / sucked up by that great green dragon”. The poem is not so much a howl of pain, but rather an urgent expression of an all-consuming desire – the irrepressible desire to be overpowered by a force greater than oneself.

6. The Starry Night, Anne Sexton (1961)

The town does not exist

except where one black-haired tree slips

up like a drowned woman into the hot sky.

The town is silent. The night boils with eleven stars.

Oh starry starry night! This is how

I want to die.

It moves. They are all alive.

Even the moon bulges in its orange irons

to push children, like a god, from its eye.

The old unseen serpent swallows up the stars.

Oh starry starry night! This is how

I want to die:

into that rushing beast of the night,

sucked up by that great dragon, to split

from my life with no flag,

no belly,

no cry.

The Disquieting Muses, de Chirico, 1918

The unsettling mood of De Chirico’s painting is not only matched but heightened in Sylvia Plath’s disturbing poem in which she imagines her childhood self haunted by three faceless muses, who recall the Three Fates of classical mythology, as well as other trios of sinister women from myth and literature. With their terrifying blank faces, they “stand vigil” over her, their strange figures, like de Chirico’s painting, casting their long shadows “in the setting sun / That never brightens or goes down”.

7. The Disquieting Muses, Sylvia Plath (1957)

Mother, mother, what ill-bred aunt

Or what disfigured and unsightly

Cousin did you so unwisely keep

Unasked to my christening, that she

Sent these ladies in her stead

With heads like darning-eggs to nod

And nod and nod at foot and head

And at the left side of my crib?

Mother, who made to order stories

Of Mixie Blackshort the heroic bear,

Mother, whose witches always, always,

Got baked into gingerbread, I wonder

Whether you saw them, whether you said

Words to rid me of those three ladies

Nodding by night around my bed,

Mouthless, eyeless, with stitched bald head.

In the hurricane, when father's twelve

Study windows bellied in

Like bubbles about to break, you fed

My brother and me cookies and Ovaltine

And helped the two of us to choir:

"Thor is angry: boom boom boom!

Thor is angry: we don't care!"

But those ladies broke the panes.

When on tiptoe the schoolgirls danced,

Blinking flashlights like fireflies

And singing the glowworm song, I could

Not lift a foot in the twinkle-dress

But, heavy-footed, stood aside

In the shadow cast by my dismal-headed

Godmothers, and you cried and cried:

And the shadow stretched, the lights went out.

Mother, you sent me to piano lessons

And praised my arabesques and trills

Although each teacher found my touch

Oddly wooden in spite of scales

And the hours of practicing, my ear

Tone-deaf and yes, unteachable.

I learned, I learned, I learned elsewhere,

From muses unhired by you, dear mother

I woke one day to see you, mother,

Floating above me in bluest air

On a green balloon bright with a million

Flowers and bluebirds that never were

Never, never, found anywhere.

But the little planet bobbed away

Like a soap-bubble as you called: Come here!

And I faced my traveling companions.,

Day now, night now, at head, side, feet,

They stand their vigil in gowns of stone,

Faces blank as the day I was born,

Their shadows long in the setting sun

That never brightens or goes down.

And this is the kingdom you bore me to,

Mother, mother. But no frown of mine

Will betray the company I keep.

Nude Descending a Staircase, Duchamp, 1912

Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase was shown at the famous 1913 Armory Show in New York, where it naturally caused a stir. By then the father of conceptual art had decisively rejected what he dismissively termed “retinal art” and in the same year produced Bicycle Wheel, his first ready-made and the world’s first kinetic work of art. X.J. Kennedy captures the figure’s unthinking, mechanistic movement – “A constant thresh of thigh on thigh.”

8. Nude Descending a Staircase, X. J. Kennedy (1961)

Toe upon toe, a snowing flesh,

A gold of lemon, root and rind,

She sifts in sunlight down the stairs

With nothing on. Nor on her mind.

We spy beneath the banister

A constant thresh of thigh on thigh--

Her lips imprint the swinging air

That parts to let her parts go by.

One-woman waterfall, she wears

Her slow descent like a long cape

And pausing, on the final stair

Collects her motions into shape.

L'Estaque, Cézanne, 1883

Cézanne painted around 20 views of L'Estaque, a fishing village just west of Marseille. These show the change of seasons and the shifting patterns of light at different times of day. However, the artist strove to achieve a sense of timeless monumentality that he felt was missing from the work of the Impressionists. Here Allen Ginsberg looks beyond what he believes the painting merely describes and toward a transcendent reality that "doesn't occur on the canvas". Beyond the bay, and away from the foreground where we find "time and life / swept in a race", is, he says "Heaven and Eternity".

9. Cézanne's Ports , Allen Ginsberg (1950)

In the foreground we see time and life

swept in a race

toward the left hand side of the picture

where shore meets shore.

But that meeting place

isn't represented;

it doesn't occur on the canvas.

For the other side of the bay

is Heaven and Eternity,

with a bleak white haze over its mountains.

And the immense water of L'Estaque is a go-between

for minute rowboats.

Diana and Actaeon, Titian, 1556-59

Titian’s painting depicts a scene between Diana and Actaeon from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. It shows the moment of accidental discovery as Actaeon, after a day's hunting, spies the naked Diana bathing with her nymphs. Actaeon is at once transformed into a stag and is chased and killed by his own dogs, who do not recognise him. Szirties’ poem begins with a quote from Donne’s Elegy XX (From His Mistress Going to Bed): “O My America, My Newfoundland”, a tantalising play on sexual discovery and conquest. The poem is told from the point of view of Actaeon, with Diana taking on a strange and somewhat sinister role - “you, drinking / night water” reads as an accusation from the mouth of one unjustly wronged but admitting of his desire all the same.

Titian’s painting depicts a scene between Diana and Actaeon from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. It shows the moment of accidental discovery as Actaeon, after a day's hunting, spies the naked Diana bathing with her nymphs. Actaeon is at once transformed into a stag and is chased and killed by his own dogs, who do not recognise him. Szirties’ poem begins with a quote from Donne’s Elegy XX (From His Mistress Going to Bed): “O My America, My Newfoundland”, a tantalising play on sexual discovery and conquest. The poem is told from the point of view of Actaeon, with Diana taking on a strange and somewhat sinister role - “you, drinking / night water” reads as an accusation from the mouth of one unjustly wronged but admitting of his desire all the same.

10. Actaeon, George Szirtes (2012)

O, my America, my Newfoundland

John Donne, "Elegy 20"

O, my America, discovered by slim chance,

behind, as it seemed, a washing line

I shoved aside without thinking –

does desire have thoughts or define

its object, consuming all in a glance?

You, with your several flesh sinking

upon itself in attitudes of hurt,

while the dogs at my heels

growl at the strange red shirt

under a horned moon, you, drinking

night water – tell me what the eye steals

or borrows. What can't we let go

without protest? My own body turns

against me as I sense it grow

contrary. Whatever night reveals

is dangerously toothed. And so the body burns

as if torn by sheer profusion of skin

and cry. It wears its ragged dress

like something it once found comfort in,

the kind of comfort even a dog learns

by scent. So flesh falls away, ever less

human, like desire itself, though pain

still registers in the terrible balance

the mind seems so reluctant to retain,

o, my America, my nakedness!

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)