Linnaeus Tripe? Shades of a minor character in Dickens or Trollope, but in fact the resoundingly named Tripe (1822-1902) was an army officer and photographer, the sixth son and ninth child of a professional middle-class family from Devonport, his father a surgeon in the Royal Navy. He joined, as so many of his background did – younger son, but of a certain social status – the East India Company’s army (the 12th Madras Native Infantry) aged only 17, the third Tripe son to do so. The Company was the de facto and implacable foreign ruler of India until, following the trauma of the Indian Mutiny of 1857, the British government took over completely from the Company’s private forces.

Tripe got to know southern India well with various postings, and learnt Hindustani. He was thus in a very real sense embedded as a serving officer before he turned his photographic eye on the astonishing sights all around him. It was the Great Exhibition of 1851 that put photography on the world map of human invention and innovation, and Tripe, home in England on leave, joined the Photographic Society as a founder member. He had found a new and surprising skill, using the most advanced equipment then possible, and printing from waxed paper negatives. Now we can see in this pioneering exhibition just what a remarkable oeuvre he produced in the newfound medium.

In turning his attention to the material evidence of Indian and Burmese culture, Tripe was however working in a grand tradition. For even from the inception of the Company, the British abroad were also passionate students, somewhat self-serving but also genuinely absorbed, in the languages, histories and topographies of these exotic countries and cultures. Yes, the more they knew the more effectively they could serve their own objectives, but ironically the more they investigated their surroundings, past and present, the more these amazingly energetic amateur gentlemen scholars contributed to a growing store of original and useable knowledge. And Tripe was commissioned by several official bodies, including the Company, to make the documentary records that he did. (Pictured below: Amerapoora: Corner of Mygabhoodee-tee Kyoung, 1855.)

However, it was his own vision that transformed these views into something beyond the reportorial. In a show that reaches beyond the specialist history of photography, this exhibition of some 60 original prints is a finely honed selection of the work of a superb, enlightening and significant artist.

However, it was his own vision that transformed these views into something beyond the reportorial. In a show that reaches beyond the specialist history of photography, this exhibition of some 60 original prints is a finely honed selection of the work of a superb, enlightening and significant artist.

On his return to the subcontinent from his three-year leave in England, Tripe was commissioned to photograph in the kingdom of Mysore, the territory in the south of the subcontinent known to the East India Company as the Madras Presidency, and Burma. His technical expertise and innovation were also crucial; he found ways of overcoming distortion, and he retouched and titivated his images. Tripe was a photographer of landscape – bridges, roads, rivers, villages and overarching skies with clouds artificially heightened and retouched in the darkroom. But above all, his subject matter expanded to architecture – eastern idioms practiced over centuries for the creation of spectacular, beautiful, elaborate temples and palaces, an architecture never seen before by westerners.

His career as the narrator of the material greatness of Burma and India lasted less than a decade; it was stifled all too soon by civil service Kafka-like bureaucracy. But the prodigious results are invaluable historical documents – even more valuable as it was not necessarily part of the rich indigenous cultures to deal with notions of history, preservation and conservation. Tripe shared in that impulse to order and record, so characteristic of Victorians, and in so doing has provided a priceless legacy. And with Tripe it was even more: his photographs are interpretative records deftly exploiting light and shadow. They vividly show the detailed magnificence of centuries of sacred buildings, and they are genuine and memorable works of art, worthy of their subjects.

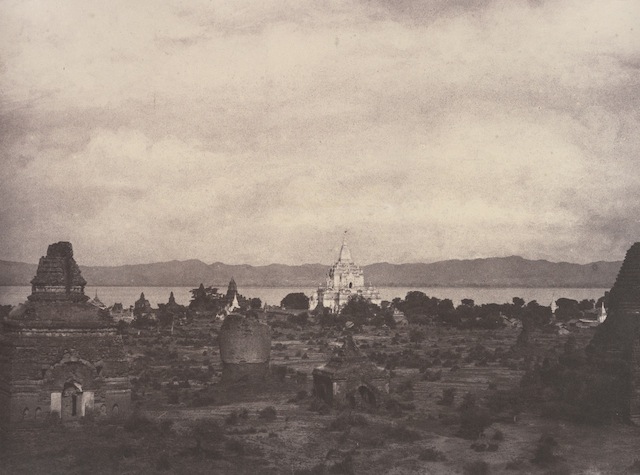

Helabid’s Temple of Siva, seen across water and close up in all its exquisitely carved detail of elephants and gods and dancing creatures and armies in procession; Jain temples in Belur; the Shwedagon pagoda in Rangoon; an enormous tamarind tree in Mysore; the vistas of endless pagodas and temples on the Burmese plain in Bagan, one of the wonders of the world; here are but a few of the subjects – and there are palaces, forts and tombs too – shown in such exquisite tones of soft browns and silvery greys. (Pictured below: Pugahm Myo: Distant View of Gauda-palen Pagoda, 1855.)

In a technical tour de force, Tripe also produced a 19 ft scroll, a composite photograph depicting the inscriptions around Tanjavur’s Great Pagoda. The cumbersome nature of early photographic apparatus is probably almost impossible to imagine in the current digital age, but the images produced by these painfully elaborate hand-done processes are far beyond current digital possibilities in their expressiveness. And Tripe’s empathetic understanding of the subcontinent, honed by his experiences in the decade before, is what elevated his imagery so far beyond the ordinary. He was a technical and aesthetic pioneer.

In a technical tour de force, Tripe also produced a 19 ft scroll, a composite photograph depicting the inscriptions around Tanjavur’s Great Pagoda. The cumbersome nature of early photographic apparatus is probably almost impossible to imagine in the current digital age, but the images produced by these painfully elaborate hand-done processes are far beyond current digital possibilities in their expressiveness. And Tripe’s empathetic understanding of the subcontinent, honed by his experiences in the decade before, is what elevated his imagery so far beyond the ordinary. He was a technical and aesthetic pioneer.

Above all, Tripe had a sense of enthusiastic curiosity expressed in his ability to convey his talent for intense observation. His imagery communicates a palpable sense of sheer delight in the complex beauties of temple and pagoda – their overarching architectural geometries of form, enlivened by intricate sculptural decoration. Go see and marvel. However, the one inescapable problem of all photography exhibitions is the parade of identically sized pictures around the wall: repetition in this way has a habit of dulling the senses – unless you take your time.

- Captain Linnaeus Tripe: Photographer of India and Burma 1852-1860 at the Victoria & Albert Museum until 11 October

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment