It’s the nature of satire to reflect what it mocks, so as you’d expect from a British Museum exhibition curated by Ian Hislop, I object is a curiously establishment take on material anti-establishmentarianism from BC something-or-other right up to the present day.

As wheezes go, it’s a fairly good one, a jaunty riposte to the extraordinary plumbing of the museum’s archives conducted by then-director Neil MacGregor through the series A History of the World in 100 Objects. As a premise for collecting together absorbing objects it’s unconventional, but it suffers from continued-on-p.94ism and objects have to fight against shonky curation for attention.

An absorbing section dedicated to defaced bank notes (a criminal offence in most countries - but not the US) helpfully blows up details as enlarged wall stickers but omits to translate the Chinese anti-Communist party message on the one yuan note. Labels are titled with jokes but often lack context and the sense is of accidental censorship which elevates the anti-authoritarian impulse above the nuances of the act. The show never quite escapes the sense of being a personal tour round the humorous proclivities of Lord Gnome himself (insert Glenda Slaggism of choice here).

An absorbing section dedicated to defaced bank notes (a criminal offence in most countries - but not the US) helpfully blows up details as enlarged wall stickers but omits to translate the Chinese anti-Communist party message on the one yuan note. Labels are titled with jokes but often lack context and the sense is of accidental censorship which elevates the anti-authoritarian impulse above the nuances of the act. The show never quite escapes the sense of being a personal tour round the humorous proclivities of Lord Gnome himself (insert Glenda Slaggism of choice here).

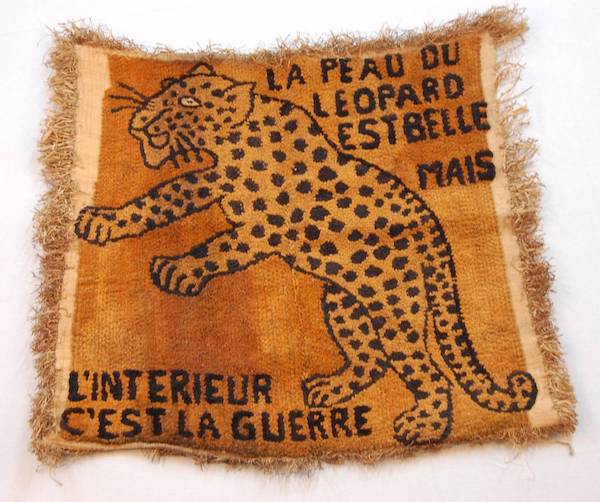

Nevertheless, it throws up some astonishing artefacts. A King James Bible containing a grauniad-worthy printing error that cost its printer a £300 fine (“Thou shalt commit adultery”) and a censored copy of Boccaccio with the excised passages restored in its owner’s hand speak for the power of the printed word. A Catholic salt cellar constructed of broken up reliquaries and imbued with symbolism (garnets for Christ’s blood, rock crystal for purity) and a Congolese wall hanging (pictured above) which coopts the figure of the leopard so favoured by Mobutu both exhibit how domestic settings and ambiguous meanings allow for plausible deniability when authoritarian regimes exert religious or political control.

Some of the most fascinating pieces on show are textiles. A Kenyan kanga ingeniously wraps a political slogan in a Kiswahili proverb and a photograph of Yasser Arafat in the Oval Office shows how he folded his kiffeyeh into the shape of the Palestinian state. A silk scarf from the Merina of Madagascar neatly illustrates both the traditional clothes Radama II forbade during his pro-European reign and the weapon by which he was strangled.

Other objects demonstrate humour's efficacy in conveying messages strikingly. A Pussyhat (pictured left) gleefully and furiously inverts Trump’s standard come-on tactic (“grab ‘em by the pussy”) into millions of pink-headed protestors marching against his occupancy of the White House (you mean presidency. Ed.). An example poster of The Zimbabwean’s Trillion Dollar campaign which won advertising awards criticised the rate of inflation under Mugabe while also upping its circulation. But the power of both comes from their smartly-formed messages, not from their drab current surrounds.

Other objects demonstrate humour's efficacy in conveying messages strikingly. A Pussyhat (pictured left) gleefully and furiously inverts Trump’s standard come-on tactic (“grab ‘em by the pussy”) into millions of pink-headed protestors marching against his occupancy of the White House (you mean presidency. Ed.). An example poster of The Zimbabwean’s Trillion Dollar campaign which won advertising awards criticised the rate of inflation under Mugabe while also upping its circulation. But the power of both comes from their smartly-formed messages, not from their drab current surrounds.

Whether the work of a single dissident (as with the fake Czech koruna designed in 1957 by Marie Uchytilová-Kučová and still in circulation in 1989) or the result of a meticulously-planned campaign, I object shows the conviction and means by which people make their voices heard. The exhibition lacks coherence but its anarchic rabble of objects reflects how each clamours to claim your attention. Apt, perhaps.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)