Several hundred photographs, of varying scales and most of them newly printed gelatin silver prints in superb tones of greys blacks and whites, take us into a world that has been subliminally familiar to us for nearly 50 years.

Stardust is the title given to this self-selected retrospective, three years in the making, the photographer his own curator, and the word neatly encapsulates the fascinating conundrum of photography itself. As Bailey himself puts it, “it’s not the camera that takes the picture, it’s the person” and these photographs are as much about Bailey as his subject - his terrific insouciance, his seemingly natural, unforced, spontaneous eye, his alert rapidity when working. His is the stardust, for he makes his subjects – from the tribesmen of Nagaland, aborigines, and the ornamented peoples of Papua New Guinea, the models for Vogue, the politicians, entertainers, writers and artists – stars. Some can even appear strikingly unfamiliar: the boyish Damon Albarn is anguished. The spectrum from Mick Jagger’s masculinity to his androgyny and even prettiness, framed by a fur hood, is strikingly portrayed.

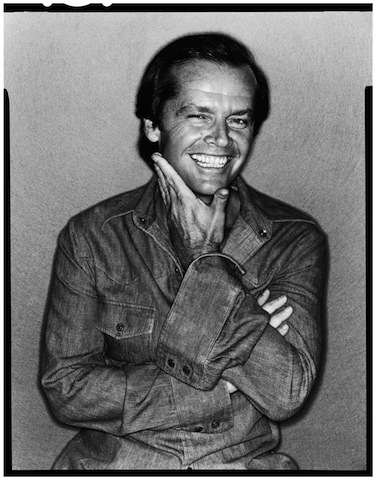

The hypnotically demanding rightness of his pictures is as verbally inexplicable as the charisma and physical presences of Jack Nicholson (pictured right), or Kate Moss, neither conventionally good-looking, and he is as adept at conveying the gentle dignity and profound resilience of Nelson Mandela as he is the irritating bravura of East End hardmen. We see scores of the most memorable and most photographed (and the two are linked, although the ubiquitous nature of photography and consequent inescapable memorability, are not totally responsible for each other) through Bailey’s candid and determinedly unsparing, although surprisingly affectionate, eye.

The hypnotically demanding rightness of his pictures is as verbally inexplicable as the charisma and physical presences of Jack Nicholson (pictured right), or Kate Moss, neither conventionally good-looking, and he is as adept at conveying the gentle dignity and profound resilience of Nelson Mandela as he is the irritating bravura of East End hardmen. We see scores of the most memorable and most photographed (and the two are linked, although the ubiquitous nature of photography and consequent inescapable memorability, are not totally responsible for each other) through Bailey’s candid and determinedly unsparing, although surprisingly affectionate, eye.

There are scores of beautiful women – several of whom he had extended liaisons with, and indeed married – Jean Shrimpton, Catherine Deneuve, Marie Helvin, and his current wife of over 30 years, another model, Catherine. Bailey himself declares that he was never really interested in fashion. He did fashion, he says, irresistibly, because he liked what was in the frocks.

And in turn his sitters liked sitting. Or standing, jumping, and lying down. He climbed (in)famously in bed with Warhol (Warhol’s condition for co-operation), and we see the very young Marianne Faithfull lying wistfully supine in an urban field, a lamppost in the background emphasising the diagonals of her resting torso. Angelica Houston, whose face should not have worked according to Bailey, but who nonetheless granted her great beauty, said working with Bailey was an adventure. He was teasing, flirtatious and witty.

Not for Bailey the snapshot, the decisive moment. Everything is deliberate. The simplicity of the studio without props – just a plain white background, is peculiarly reminiscent of Irving Penn’s travelling studio of white sheets. It ensures the focus is intensely on the subject. But on Bailey’s travels, the environment is part of the ensemble, the poverty-stricken yet amazingly elaborate interiors of the natives of Nagaland as important as the dusty vast landscapes of Australia in which he photographed aboriginals, whose initial suspicion and indeed dislike of any camera was allayed by the photographer.

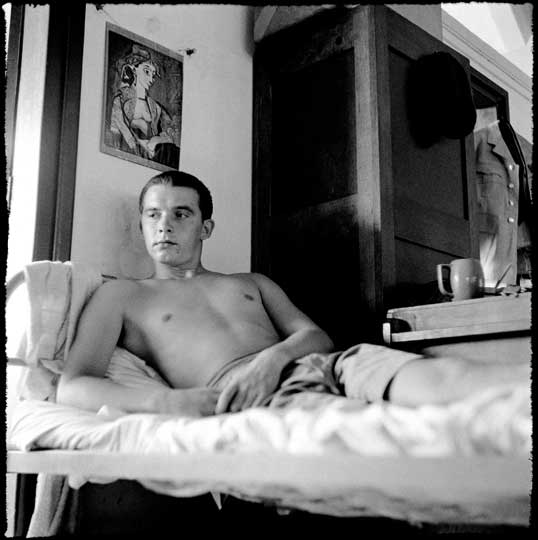

Bailey is, like Hockney, addicted to experiment. (Pictured left: Self-Portrait, 1957.) He started with the Box Brownie, the family camera, then graduated to 35mm, to Polaroid, to digital in all its manifestations, and to the current phone camera. One fascinating section is his use of the film camera, the 11 X 14, about, as he says, £200 per click, with the developed image actually smaller than the negative. Here the subjects are against black; a very anguished skull-like Joseph Beuys, Mick Jagger scowling. A whole room is devoted to the Stones.

Bailey is, like Hockney, addicted to experiment. (Pictured left: Self-Portrait, 1957.) He started with the Box Brownie, the family camera, then graduated to 35mm, to Polaroid, to digital in all its manifestations, and to the current phone camera. One fascinating section is his use of the film camera, the 11 X 14, about, as he says, £200 per click, with the developed image actually smaller than the negative. Here the subjects are against black; a very anguished skull-like Joseph Beuys, Mick Jagger scowling. A whole room is devoted to the Stones.

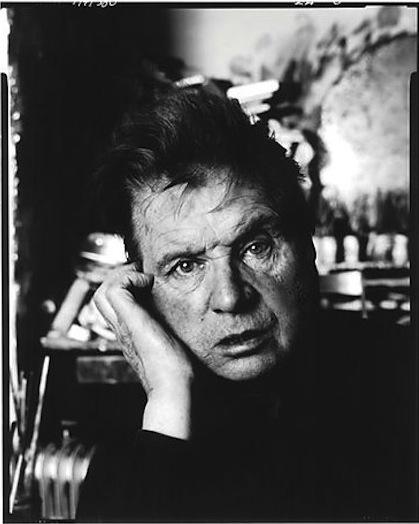

His unassuming and attractive confidence also leads to a fine sequence of fellow photographers, from Cartier-Bresson, whom Bailey regards as a surrealist, to Bruce Weber, a rare outdoor shot of the photographer and his dogs. Francis Bacon (main picture) was almost an obsessive subject (a painter absorbed by what a photographic vision could mean).

There is a very rare descent into a kind of sentimentality, even mawkishness, in a wall of imagery devoted over decades to his fourth wife Catherine, each photograph unlabelled, with several of one of their babies being born; and a wall of still lifes in colour with skulls, an unnecessary meditation on mortality, for photography usually does not function well as a vehicle for the posed vanitas. Neither worship nor intimations of mortality work well for Bailey. Life, from its inescapable banality to its irrepressible vitality, is his metier.

There are four vitrines of books and ephemera which amplify a career based on an astonishingly high level of visual scrutiny, a striking imagination which, using minimal external props, manages to hone in with a laser-like intensity on something essential that portrays a believable persona for each subject – whether already a colossus, an emerging star, or an “ordinary” person. The visitor somehow feels on surprisingly intimate terms with these people whom we will never know, and that somehow Bailey makes us feel we do.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment