The Great Unknown, the Last Enemy, the Big Sleep… it’s death we’re talking about, and Dan Cruickshank’s affectingly personal film succeeded in reaching the conclusion that there is no conclusion he could comfort himself with. “What if after death there’s nothing?” pondered Dan.

But although he expressed a wistful desire that he could share the true believer’s certainty that there is an afterlife, he seems pretty well resigned to the fact that nothing is all there is. Nonetheless, as an expert in art and architecture, he persevered in his efforts to discern whether some solace could be found in art. He studied a medieval church mural depicting the End of Days, with the lost and the saved ascending or descending according to the decision of the celestial Third Umpire, and wondered whether it had really helped prepare the cowering parishioners for death. He visited Sister Wendy Beckett, contemplative hermit and art expert. She was bracingly clear-eyed about the value of art in the face of the Beyond.

“If pictures help you to believe, fine,” she said. “But nothing could ever be adequate for it. Art can’t go through death with you.”

Maggi Hambling, who has sought a kind of artistic continuum by drawing her subjects (including her mother and writer/musician George Melly) both in life and in death, seemed able to objectify death as a challenge to her professional skills. She surmised that great artists, be they Rothko or Rembrandt, had the gift of being able to depict what it is to be alive and what it is to die at the same moment, “this kind of in-between world”.

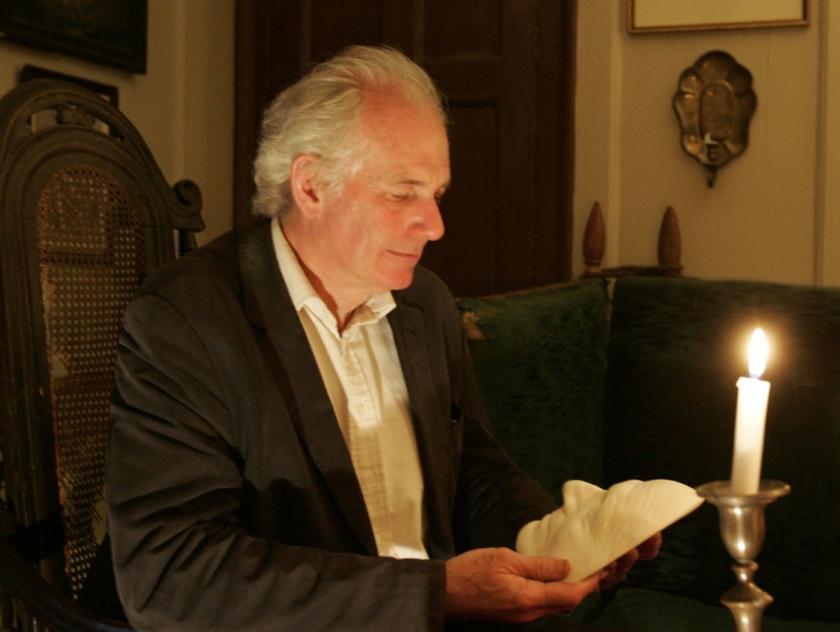

Sculptor Jamie McCartney made casts of his father both dead and alive, and discussed dispassionately the way the lack of blood pressure or muscle tone in a corpse would affect the outcome. He poured thick blue goop over Cruickshank’s face to make a mask for him. Dan studied it uncertainly. “It’s an object on which to meditate, to contemplate mortality,” he decided.

As a regular TV presenter, Cruickshank is adept at appearing in front of cameras, but unless he’s secretly the most consummate actor of his generation, what set this film apart was the impression that we were seeing his original, unexpurgated reactions. When he visited a morgue to look at a cadaver on a slab, he was wholly convincing when he described how he was shocked by “the utter detachment of life from this body”. When he described his guilt at not having created a memorial to his father, a committed Communist and atheist who’d died feeling crushed by Communism’s failure, his whole body seemed subtly warped by sorrow. It was hard to understand why he was so affected by the death of his grandfather, torpedoed in a troop ship in the First World War and thus never known to him, but affected he demonstrably was. And it was hair-raising to watch him describing how the death of his daughter Bella would be “simply beyond consolation”.

One wondered what had brought all this on. Was Cruickshank suffering a nervous breakdown? Had he experienced a premonition of his own death? His mental agitation certainly wasn’t soothed by his decision to visit Nick Serpell, the BBC’s obituaries editor, and read his own pre-prepared entry – “the scarf and Panama hat gave him the appearance of a colonial traveller, coupled with his somewhat breathless and over-excitable demeanour…” Serpell explained, not very apologetically, that he’d judged Cruickshank to be worth “a fairly average length” obituary of 700 words.

Cruickshank looked stunned, to an almost comical degree, and had to go and sit down. “It’s terrifyingly sobering,” he muttered, beginning to resemble an elderly antiquary from an M R James ghost story, pursued by a nameless demon that he had unwittingly unleashed. Sometimes the unknown is better left that way.

Add comment