Johnny Marr’s second single as a solo artist, New Town Velocity, describes his youthful propulsion by pop music in grey late Seventies Manchester towards a bright, boundless future he duly reached with The Smiths. It surely also describes the renewed energy he’s drawn from being back in his home city after five years in Portland, Oregon. Manchester certainly inspired this year’s debut solo album The Messenger, with its resourcefully melodic rock rooted in local inspirations such as Magazine and his own past with The Smiths, so often disavowed till now.

Born in Manchester in 1963, the teenage Marr found an outlet for a voracious love of music from the Stooges to the Buzzcocks, Bert Jansch and Chic by knocking around in bands with older musicians, singing when he had to. He rang the doorbell of Stephen Patrick Morrissey, locally known as a lyricist and four years his senior, in 1982, certain before they’d done anything that it was a mythic pop moment. “This is how Leiber and Stoller got together,” he told his host. Their intuitive understanding was so immediate that ideas for four songs were conjured together as they spoke.

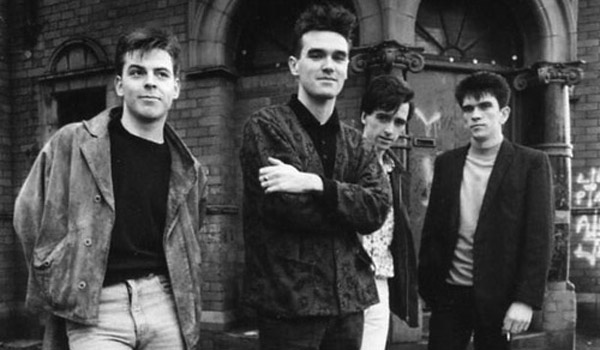

They formed The Smiths (pictured above) that year with Andy Rourke (bass) and Mike Joyce (drums). The group recorded four studio albums and two more scooping up the singles and radio sessions of a relentlessly prolific five years before Marr, cracking from the strain, quit on the eve of Strangeways, Here We Come’s 1987 release. The Smiths had been the most important British band of the Eighties, mining the deepest depths of adolescent emotion with humour, empathy, sonic adventure and beauty. Marr’s imaginative rock and pop classicism, in that decade of synthetic over-production and yuppie over-consumption, was part of their defiant outsiders’ stance.

They formed The Smiths (pictured above) that year with Andy Rourke (bass) and Mike Joyce (drums). The group recorded four studio albums and two more scooping up the singles and radio sessions of a relentlessly prolific five years before Marr, cracking from the strain, quit on the eve of Strangeways, Here We Come’s 1987 release. The Smiths had been the most important British band of the Eighties, mining the deepest depths of adolescent emotion with humour, empathy, sonic adventure and beauty. Marr’s imaginative rock and pop classicism, in that decade of synthetic over-production and yuppie over-consumption, was part of their defiant outsiders’ stance.

That was five years of Johnny Marr’s story. While Morrissey has built a solo career from his own, unchanging personality, Marr has spent the last quarter-century, no less proudly, supporting others with his music, on tour (the Pretenders), in stray collaborations (Billy Bragg’s “Sexuality”, Bryan Ferry), and five bands: The The, Electronic, the Healers, Portland, Oregon’s Modest Mouse and Wakefield’s The Cribs.

His tale will probably always be seen through The Smiths’ prism. But The Messenger’s release has put him centre-stage. At Manchester’s Parklife Weekender in June, he played to a crowd as young as he was when his musical fire was first lit, new songs standing proudly alongside Smiths tunes played with incendiary majesty. The calls to reform his old band look lazy and redundant, when Marr’s past and present sit in such productive harmony. Ahead of appearing at the Reading and Leeds festivals, he talks theartsdesk through his questing musical life.

NICK HASTED: Were your early teenage years a time that you wanted to throw yourself into as much as you possibly could?

NICK HASTED: Were your early teenage years a time that you wanted to throw yourself into as much as you possibly could?

JOHNNY MARR: Oh yeah. When I was 14 (pictured right), I’d bunk off school to go hanging around town. I was pretty adventurous, a little Perry boy, with my flick. I saw a lot of gigs at that time, I’d been going to them for a while - but a Patti Smith show around then was a bit of a life-changer. A lot of gigs you see around that time and records you get are really important. And I loved Iggy, and I loved the [New York] Dolls. It was a really exciting time, you know. It was one of the reasons I just walked out of school. Because what was going on outside was a world of promise, and getting into town and looking at record covers, and waiting for my girlfriend - having a head full of ideas about being in a band and trying to get a decent guitar were my full-time preoccupation. I was never bored.

Were you studious in other ways - in finding out about pop, and how it was made, and what it would mean to you?

Yeah, absolutely. All my friends were older, and were very smart. So I was incredibly studious in what I was interested in.

So you were studying the life you wanted to live?

Yeah, I was. I was starting to be asked to join a lot of older bands by that time, and finding my feet. I was very aware that it was good to be young, and I was aware that the bands and records I liked could be the soundtrack to my life. So I was completely obsessive at finding out everything about everyone I could, and trying to learn to write songs around that time. And riffs - how many riffs I had. All my friends were doing the same thing, but they were older.

Did pop give you ambition for yourself?

I think pop gave me obsession. I was already completely music mad and I had loads of records, because I come from a family of record collectors. So I was always really obsessive about what music actually did to you when you listened to it. But in terms of it being the life I was going to lead, it was all starting to come together around the time I was 14. I made a decision that it was going to be my life, come what may. Unless you’re really stupid, you don’t expect that it’s going to happen 100 percent, but you just go for it.

You were 19 when you formed The Smiths. What was it like being in them in the very early days?

It was very exciting, and everybody was really happy, most of the time. As a writer I’d honed my craft. When I was 14, it was the start of something, of learning to put guitar songs together - and then The Smiths was the result of it. Because even early on for The Smiths, around the time of “This Charming Man”, we were very prolific. Songs were pouring out of us. Lots of new things were happening, new people coming into our lives, having signed to a label, Rough Trade. It’s nice to reminisce about those things, because it was as exciting for everybody working with us as it was for the band themselves. As I remember, most people who came on board were also fairly young, and our success was so explosive, that it was contagious to everybody who was involved, fans and crew and band alike.

Was it a time of great promise, but all the promise was also being realised?

Yeah, promise was being realised. And the other thing about us was there was something fabulous going on every day, which continued right the way through the life of the band, and I’m lucky to say, most of my life. Some people might call it very hard work, which is also valid, but I just thought it was what I’d wanted to do all my life.

Was someone like Morrissey the catalyst you needed?

Well, absolutely, because I had a songwriting partner, and he and I formed a group together. There was almost a year when it was just me and him in the trenches trying to find other people, and trying to get something going, but we were writing songs. But there were other people too who were catalysts. Joe Moss the manager was an important figure for us. Geoff Travis, [manager] Scott Pearing, you could say - John Peel. And making the decision to go back and get Andy [Rourke] in the band. And Mike [Joyce] too. All the characters were absolutely right.

Had things changed by the time of the final Smiths album, Strangeways Here We Come, in 1987?

Had things changed by the time of the final Smiths album, Strangeways Here We Come, in 1987?

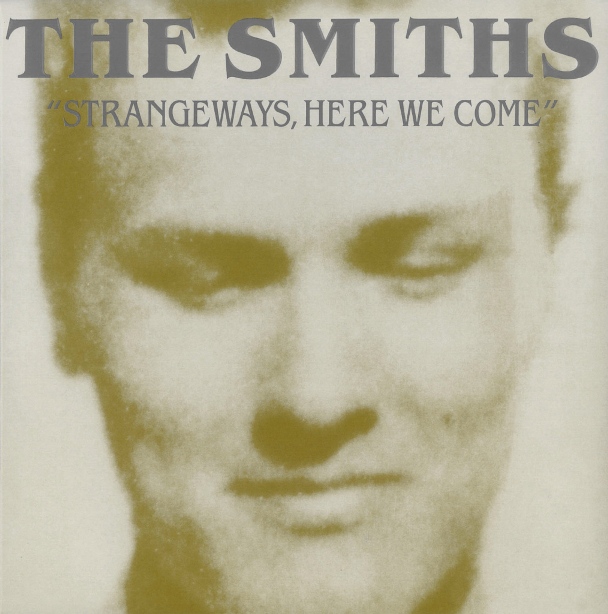

We were very serious about what we were doing, and there was a weightiness about the group by then, which makes sense. We’d made a lot of records. I think we transcended being a pop band at that time. We meant something different. We were established and I’d say heavy - which I’m pleased about. I don’t play any records that I make, but Strangeways was always my favourite, because I think that it’s a brave record. There was an atmosphere that needed to be captured on that record, that I wanted to capture, and the way to do it is to leave some things open, and not to cram it with too much stuff, and I think that takes a certain sense of purpose, and bravery. So the production doesn’t have tons of overdubs, and the songs breathe a little bit, and it has a slightly unresolved atmosphere. There is space in it, and that was a conscious thing. I knew that the record was good at that time.

I remember the reaction to it was handicapped by what happened to the band [The Smiths split in August 1987, the month before Strangeways’ release], and it took me a few years to realise just how great that record is.

I’m glad you like it, that’s cool.

But at that distance, how do you feel about the way things ended? Is there still any sadness attached to it?

Err…no, it’s so long ago, it’s just part of my life story now. It would have been so much better if it had happened in a different way. But we were all very young, still. And there was a lot at stake, and so you can always look back 30 years later on a break-up and see that it was a shame the way things happened. But that’s understandable.

You worked with Bryan Ferry (pictured right with Marr) around that time, didn't you?

You worked with Bryan Ferry (pictured right with Marr) around that time, didn't you?

Bryan contacted me through someone at the record company. Because he’d heard a Smiths instrumental track, “Money Changes Everything”, and he really liked it, and that turned into “The Right Stuff”, and he really loved it, and had some ideas to sing on it. And we were all thrilled that he came down to the studio. I think I played on Bryan’s record in ’87, The Smiths were still going, but timing’s a strange thing, so when Bryan’s single “The Right Stuff” [from his album Bete Noire] came out it was just after The Smiths split, even though it was done quite a while before that. Bryan’s always interesting. He’s very modest, so I nudge him to tell me about different things he’s done, from painting, to microphones. He’s always been one of my all-time favourite singers, and he’s a real artist. His process and the way he approaches things and his mind-set is like a painter or a sculptor.

One of the ways he’s interesting is that he’s a Northern working-class bloke who’s transformed himself into this other persona - he wanted to be something else, and he succeeded.

Yeah. Bryan’s journey from his Northern roots to what he became is a very striking example of what some people can do. Particularly because what he became is so far from what you imagine a coal miner’s son from Durham started out as. But as a person he’s very refined, and there’s a grace about him naturally, in the way he moves and the way he speaks. He is genuinely cool. But he gets very excited when music is coming together at the right time. He always says, “I don’t know what it is, but I will when I hear it,” which is a real painter’s approach. But yeah, we do have a Northern connection, and that was very clear from the off.

Then the next year you toured with the Pretenders - the first time you’d toured with a band that wasn’t The Smiths. Did that feel a bit strange?

The Pretenders had a tour with U2 to finish in 1988 - LA, San Francisco - and Robbie McIntosh had left, and I just wanted to play my guitar, and get away from all the fuss going on about the Smiths split. It was strange because I’d come out of being in the one band for five years, but because I’d played with different bands in my teenage years, I liked clicking with different musicians and being thrown into different situations. So that apprenticeship was already part of my life. But I was a very lucky person to have had a friendship with Chrissie [Hynde], because not only is she very funny, but she’d been through a lot of really dramatic, life and death things with her own band [guitarist James Honeyman-Scott died of a drug overdose in 1982, and drummer Pete Farndon also fatally overdosed the following year], and that helped me get my own very dramatic stuff into some kind of perspective. It didn’t make it any less dramatic, but…

But no one died in The Smiths…

Yeah. It’s funny how in life the right person shows up, even if it appears to be very random.

Then your next band after The Smiths was The The. You could have been in them instead of The Smiths years before, as I understand it?

Then your next band after The Smiths was The The. You could have been in them instead of The Smiths years before, as I understand it?

Yeah, The The was the next band that I was in after The Smiths full-time. For Matt [Johnson, The The’s singer-songwriter, pictured with them second right] and I, it was very natural because we’d known each other since 1980, and it seemed like unfinished business, or something that we were always going to get down to. The timing was really right for Matt, because he’d already done Soul Mining and Infected, and wanted to try the new thing of having a fixed band. And Matt was just totally respected by everybody, super-smart and a heavyweight thinker.

What did you find yourself talking about?

Well again, it really felt like a forward move for me personally as well as musically, because musically tackling the existing The The songs meant that I had to tackle all of these weird things that he’d done on records at 4 o’clock in the morning, which made me a much better guitar-player. And on a personal level it was all about big stuff. Whether it was Noam Chomsky, or he turned me onto Gore Vidal and esoteric things, a lot of philosophy, a lot of different books, anything from Norman Mailer to F. Scott Fitzgerald and William Blake, and really serious political thinking, a lot of world politics, movies. Matt just had this incredible appetite for the modern world and a certain kind of culture. So it was very inspiring, and Matt’s also a very tough and strong person, which again was handy to have in a friend.

So that self-education you started with was carrying on apace?

Absolutely. The The were very into everything from [Einsturzende] Neubauten to Tim Buckley. So yeah, a really inspiring situation to be in. I loved it.

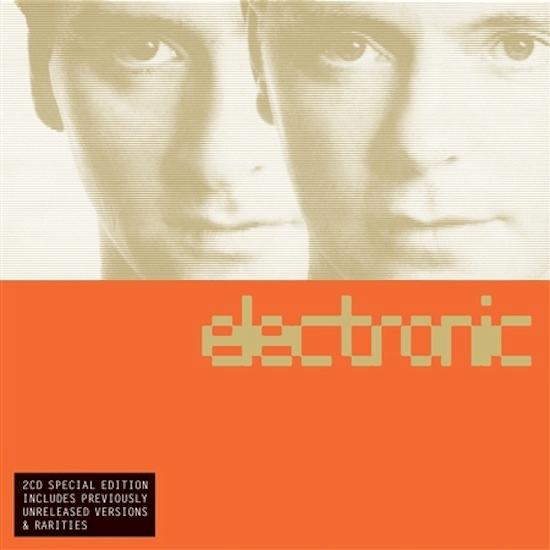

Electronic seemed a radical change from all that when you began it with Bernard Sumner (pictured right with Marr on the cover of their self-titled debut) in 1989, just as Madchester conquered Britain.

Electronic seemed a radical change from all that when you began it with Bernard Sumner (pictured right with Marr on the cover of their self-titled debut) in 1989, just as Madchester conquered Britain.

The music world was getting a little bit different, and mine was. What had started happening in Manchester in ’87, ’88 was just a big part of a sea-change in the culture. So much of it, as so often, was technology-led, and a lot of good underground music was coming out to be inspired by, whether it was under the dance banner or the electronic banner or what doesn’t really matter. Bernard [Sumner] had asked me to do something with him in ’87, and we’d started to get together in my studio most weekends, piling up ideas and just getting to know each other. I’ve been asked whether Electronic was a sanctuary for both Bernard and myself from our bands’ situations, and in some ways it was, but it was also very forward-looking, and there was a certain sense of liberation in us working together.

And was the appeal also that you’d been tuned into that changing culture in Manchester even in the last days of The Smiths, and this was the first chance you’d got to express that side of what you were hearing, and what you were perhaps living as well?

Yeah, exactly - what you said! I was still very young at that time, 24, 25, so I wanted to be part of what people my own age were doing, and to be involved in my times, and if you were in Manchester and not involved or influenced or taking part in what was going on, then you would’ve had to have just been pathologically standing against it or something, because it was all-pervasive, and very, very healthy as well for a few years.

It was down here where I am in London, too. I remember around that time I was standing around Piccadilly Circus one night and these girls came by in a car and said, “We’re going to Manchester, do you want to come?” and it was like the Promised Land.

[Laughs] Yeah, and looking back on it, it wasn’t just some short-term little fad. It was redefining the times, and again it’s that word heavy. Because a lot of the club music started off as pretty heavy, and then of course that permeated pop music - which is essentially how it’s been remembered, its effect on pop culture. But what was going on with the technology, and Ecstasy, and the clothes and design in a very big way, and magazines and the entire culture, had been brewing in a very interesting, big underground for a few years, and that was the inspiration for Electronic. It was a real feeling of forward motion, and of Year Zero. Which must have been amazing for Bernard, because he’s done Year Zero a few times, but that’s the kind of person he is.

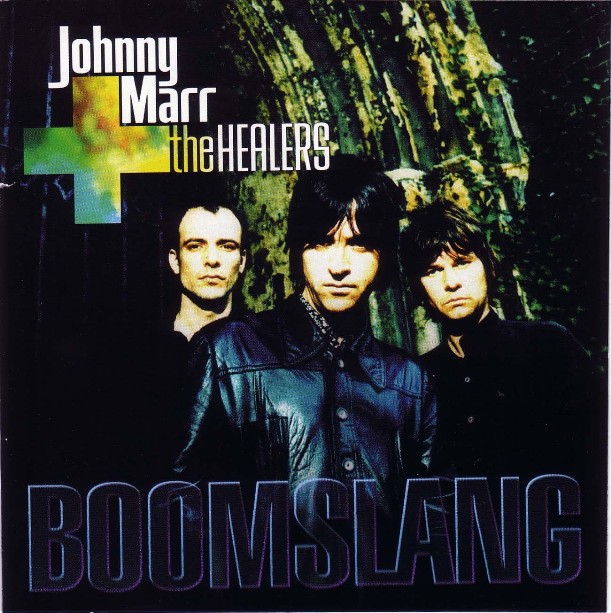

Then in 2000, with the Healers (pictured right), you finally became a singer.

Then in 2000, with the Healers (pictured right), you finally became a singer.

Bernard and I got into a working relationship for nine years, and in that time I was doing sessions with different people and playing on different records. That was a great thing. But I’d met [Ringo Starr’s drummer son] Zak Starkey in New York, and like all of my important friendships, it was very meaningful from the off, and what we were doing very quickly turned into songs. And having guys like that behind me validated what I was doing as a singer and a writer. Because The Healers started off as me writing for a very different singer, which I’d been doing for a long time. And when I found the guy, the rest of the band vetoed it, because they’d assumed that I was going to do it. And having that validation from people I respected so much was the thing that kicked me into the middle of the stage. In some of the bands when I was a teenager, I used to have to do it more by necessity than choice. But the other Healers insisted that I did, because they thought that what I was doing was more interesting, and that was an amazing compliment. Oh, and Chrissie and Matt had both said to me that I should make my own records with me singing. So all of these are people who you respect, and who love me, so then I had to take ‘em seriously. So that was a real learning curve for what I do now. And I really didn’t know how it was going to go, stepping out front, at first.

Did it feel like you were in the wrong place on stage? Did it feel unnatural?

Well I really didn’t know. But I knew the responsibilities of going out front to your band. So I just went out and did it. And in fact, in some ways it felt easier, because you’ve got a more direct connection to the audience. By that time, the people who were coming out to see us I knew were actually coming out to see me. So that was the start of me having a relationship with a crowd on that basis.

And was there, and is there now, something quite elating about that really direct connection, from the front of the stage?

Yeah, I try not to get too carried away with it. But there’s a real sense of friendship, I think. Because I think they know that I like them [laughs].

It was also around this time that you played with one of your great influences, Bert Jansch (pictured left), wasn’t it?

It was also around this time that you played with one of your great influences, Bert Jansch (pictured left), wasn’t it?

I’ve been very lucky in that I’ve got to play guitar with nearly all my heroes. And Bert Jansch was, out of all of them, the most enigmatic. He hadn’t been heard of for a number of years, and his reputation was one of real mystery and when he started to get out and play in public again, he’d heard that I was a fan. I was nervous as hell the first time I met Bert Jansch, because his reputation was one of being very inscrutable, and somewhat cantankerous, which turned out to not really be the case. He didn’t suffer fools gladly but he was lovely. And one of the greatest times of my life was when he came up to stay with me, and he got to my place and just took his guitar out and we just started playing in my kitchen. And it was the most amazing sound. We just had a style that really clicked. I didn’t try and emulate him when I was a kid, but when I first heard him I could hear similarities in our technique, and that encouraged and inspired me.

He had a subversive sound, I remember you saying.

Subversive, yeah absolutely. To describe him as a folk guitar player is really reductive. Bert, aside from his musical brilliance, made cool really mean something. His background and his values were from the late ‘50s, early ‘60s, true bohemians…

Which was a tough school in those days.

Yeah, really. The folk scene in the early Sixties was much more radical than the pop scene, and in lot of ways they’re the first real DIY punks, sleeping on floors and borrowing guitars and wearing the same clothes for months, and anything outside of that is just commercial bubblegum. And politically - it’s the beatnik thing, and he was the king of it. The most obvious tribute to Bert in my playing is the start of The Smiths’ “Unhappy Birthday”, and he’d vanished at that point.

When I saw him in the early 2000s, he was very diffident on-stage.

Yeah, that is the word for him. He wasn’t off-hand, he wasn’t unfriendly, but that’s the word that a mutual friend of mine used about Bryan [Ferry]. They’re both genuine bohemian cool.

Then the next phase in your musical life was to join Modest Mouse. How did that come about?

When Isaac Brock from Modest Mouse contacted me, I was starting to write some solo songs, and this call came out of the blue. At that time I wasn’t really liking a lot of the rock guitar music that was coming out of the UK, but I did like music that was coming out of the Northwest of America. Bands like The Shins, Built to Spill particularly, and Elliott Smith I’d liked a lot. And I knew that the kings of that music were Modest Mouse, and I knew their records, and they were brilliant and unfathomable to me, and Isaac’s invitation was a very blunt and serious one to actually join the band. I didn’t quite hear how that was going to work musically, but I was very intrigued, and I arranged to do this 10-day experiment, so I went over there, and the very first night was quite an intense, high-volume, crazed, all-night jam between me and Isaac Brock, who is the most brilliant person I’ve worked with, for many reasons. And I woke up in the early hours of the next morning in a daze, wondering if during the night we had actually written a couple of amazing songs. I was jetlagged, and a bit spaced. And I listened back to what we’d done, and I couldn’t believe it. That first night we did “Dashboard”, which when it was released became the most-played indie record on American radio that year.

And took the album that followed to no. 1...

Yeah, and started a really amazing phase of my life, of a new town once again, and new people once again, and new music and a new way of doing things, and a different kind of ideology, and it was perfect. I see part of the lineage that I started out with in my teens being about my life following where the music is. You have to put your comforts on hold to do that. But after the 10-day period in Portland, I just changed my plane ticket, and stayed out there. And the next thing I know, we’d played over 200 shows. The success was amazing, because a band like that doesn’t usually get to no. 1 of the album charts, and play 15,000-seaters. So it was good for my idealism.

And is part of that idealism for your own life - do you have to keep striking the camp and starting over every few years in order to keep moving forward, and keep honest and not stagnate? Is that just part of your mentality?

Yeah, I think I have to keep looking for new ways to do things, and be inspired by it. I always get asked whether it’s restlessness, and I don’t feel restless. I just feel like the same person I was when I started out. But I just want to know lots of ways of doing things, and try and document it with records.

Is it like you’re actually on a very committed and consistent direction, but that involves these constant musical shifts?

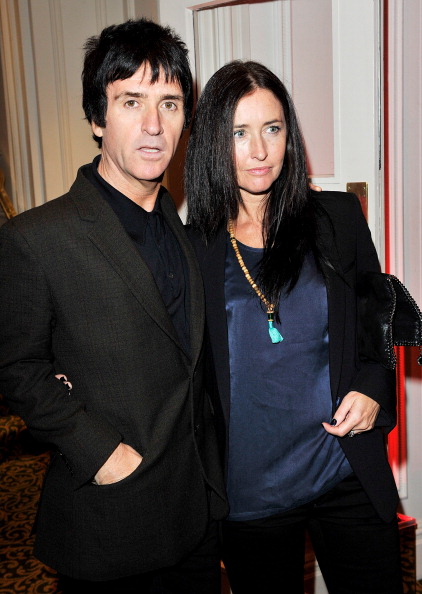

Yeah, I do feel like I’m on a committed direction, and it is part of that journey that I started as a youngster. Because when you get known for being part of a band at the start, it takes a while for people to understand the way you do things. To me, it feels like it was just me when I started out. It was actually me and Angie [Marr’s wife since 1985]. It was me at 14, and then I met Angie when I was 15, and it was me and Angie. So it’s a little odd for people, because they got to know me in The Smiths, but when I started The Smiths off, I was on my own, and with this new band, I started off on my own, and the whole thing just feels like me with this amazing, amazing bunch of friends, and incredibly talented and special people, that I’ve worked on an equal footing with, and we’ve been part of each others stories.

And has Angie (pictured left), having been there from the musical start almost, stabilised you on this course you’ve been taking?

And has Angie (pictured left), having been there from the musical start almost, stabilised you on this course you’ve been taking?

I guess we have stabilised each other, because she’s a very smart person, and also she has very good taste in music. If anyone thought of her as the demure little wife in the background, stood by the window while I’m out in the world, they have very much got the wrong idea of her, because we’re very alike, that’s the odd thing, we are very like two sides of the same coin. It was uncanny when we first met, because usually opposites attract, but we both liked doing the same things and in the same way. And it goes without saying that I know I’m very lucky. It is the most, and always will be the most important relationship in my life, obviously.

And the best luck you’ve had is meeting her, even amongst all the other people we’ve talked about.

Yeah, thanks. Meeting Angie was without doubt the best luck I’ve ever had. How we met was that there was a bus strike in Manchester in 1979, and it also happened to be snowing, and on a Friday night I had to walk miles to go to a part-time job that I hated stacking shelves in the Co-op, in order to get enough money to buy records every week, and when I’d walked all that way to this job, this witch of a boss fired me, and part of the tradition of being fired was that you had to go out the back to the loading bay, where the entire staff of this supermarket were waiting for you with an endless arsenal, palettes and palettes of eggs, and you get completely pelted, and you’re supposed to enjoy the jollity of this. Now I did mention that it was snowing, and freezing, and there was a bus strike. So I had to walk back 7 or 8 miles, as a human omelette, to my house.

Might have been worse if you'd been struck by lightning on the way...

[laughs] And amazingly, a friend of mine who came from a really cool family lived en route, and I was in so much discomfort, I nipped into his house, to have a shower and get changed, and he went to Angie’s school, and told me about this party that was going on. And not wanting to lose face, I pretended that I knew all about this party, so we just piled down to that party. So had I never got the sack, I maybe wouldn’t’ve has the best luck that I’ve ever had in my life, and met the most important person that I was ever going to meet. So that’s how that happened. We just became an item from the minute we met, and have been through the entire journey.

Now, being in Modest Mouse, how did you then find yourself in The Cribs (pictured right)?

Now, being in Modest Mouse, how did you then find yourself in The Cribs (pictured right)?

After Modest Mouse had toured, I was starting to think about doing a new record, which I was hoping to do with Modest Mouse, and at that same time I met [The Cribs’] Gary Jarman in Portland, and I only really liked two UK bands at that time, and one was Franz Ferdinand and one was The Cribs. And Gary and I struck up a friendship, and Ryan [Jarman, Gary’s brother and bandmate] knew about it, and he invited me to make a four-track vinyl EP with The Cribs, and that sounded like a really great and novel idea, so I brought some ideas for some songs, and we plugged in and immediately those songs came to life, and by the end of a couple of weeks we were looking at an LP. And it’s a funny thing but when you get involved with working with some people that you really like on a personal level, and you get into an endeavour, and particularly with something personal like making music, you want to not only make a commitment to the work, but you also want to make a commitment to the other people, because they become your friends. And in the case of Modest Mouse and The Cribs particularly, it would’ve just been too weird to bail, on a personal level. Because as all these people will tell you, we become close friends and stay close friends, and we knew the songs were good, and I started to play some of their old stuff and it sounded really good with two guitars, and we made the decision to make the record.

I know how to be in a band. Sometimes journalists will try to make a big deal to them of, “What’s it like having a legend in your band?” and will turn to me and say, “What’s it like playing with these narky kids?” which does both of us a complete disservice, and is really missing the point. It’s not like I walk onto the tour bus and there’s all these little guys playing X-box and asking me what it was like in the Sixties. The Cribs weren’t little snotty-nosed kids. When I joined they’d made a few good records, and are very smart young men, and like all my relationships, we have something in common deep down as people that makes any differences in our circumstances as people pretty superficial and secondary.

Did that apply to Hans Zimmer [once of The Buggles of "Video Killed the Radio Star" fame and now a top Hollywood soundtrack composer], who you worked with on Christopher Nolan's Inception (pictured above)? That gig got you to the Oscars...

Did that apply to Hans Zimmer [once of The Buggles of "Video Killed the Radio Star" fame and now a top Hollywood soundtrack composer], who you worked with on Christopher Nolan's Inception (pictured above)? That gig got you to the Oscars...

Yeah, the Oscars, eh? Who woulda thunk it? I loved Hans’ music for The Thin Red Line, I really think that’s an amazing piece of work, and Hans was someone I’d heard about through one or two musicians in the soundtrack world in Los Angeles and he’s got an amazing reputation, not just for his brilliance but for really being a gentleman. I don’t like bagging people - but he’s incredibly cerebral, and has the intellect of a European philosopher, and he has the soul of a rock musician. So when you get to LA to work with him, he’s been working for two weeks straight, and he’s got rings round his eyes and he hasn’t had any sleep and he’s been on a deadline, and he really needs to get home, but he’ll stay up till 2 or 3 o’clock in the morning telling you about how his mellotron caught fire in Barrow-in-Furness in 1979. He’s really genuinely an amazing composer, and the research he does into all his movies is quite amazing. And the thing that I loved about playing on Inception is that they were deceptively simple tunes that were written for me, and didn’t just suit my style but suited me emotionally. In short, you don’t know whether they’re sad or incredibly uplifting.

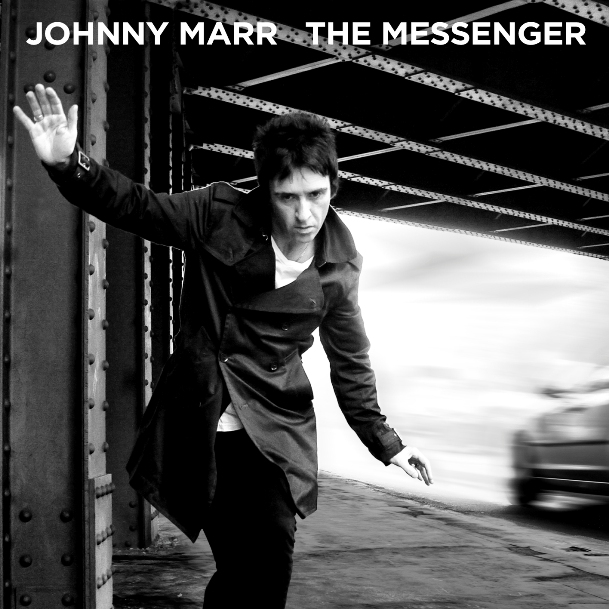

Which finally brings us to your first solo album, The Messenger (pictured left). One thing you were saying about The Healers when they started was that you wanted them to be like a Sixties Haight-Ashbury band like Jefferson Airplane, in the sense of there being a community around them. Is that communal ideal in your solo band as well?

Which finally brings us to your first solo album, The Messenger (pictured left). One thing you were saying about The Healers when they started was that you wanted them to be like a Sixties Haight-Ashbury band like Jefferson Airplane, in the sense of there being a community around them. Is that communal ideal in your solo band as well?

Yeah, I wanted to put a group together that I could call up to play on a minute’s notice and they’d be there. And that is an unusual situation, after all these years. I knew that, if I was going to do my own group at this point, I wanted us to operate in a certain way and be pretty close-knit, and not get together by arrangement too much - that we feel like this idea that I had when I started out of how bands that I used to follow used to operate, even if that’s just in my imagination. So I had this thing about how Magazine, even when they were already making records, would get together in a little cellar and come together that way. Now even if I’m wrong about it, it was a certain kind of idealism about the New Wave groups. Because you know when you’ve had a lot of success, you can be waiting around for people to finish their meetings with their interior designers, and getting together in these swanky rehearsal rooms, and a ton of crew and people around you, and it can get a bit like the raising of the Titanic. I think it’s just about being lean. All my crew are from Manchester, all my band are in Manchester, and we would be playing together even if we didn’t have shows, just to get better as a band. It is my band, but I need a group to do what I do.

So you’re still completely true to the 14-year-old boy you were at the start of all this, and what he wanted?

Yeah. I am really in many ways the same person. If you look at my band now, that could have been a picture of one of the bands I was in when I was in my teens, where I was fronting it. I think that’s good. It just reminds me how lucky I’ve been.

- Johnny Marr plays the Reading and Leeds festivals August 23-25, and tours the UK from October 18. The Messenger is out now on Warner Bros.

Add comment