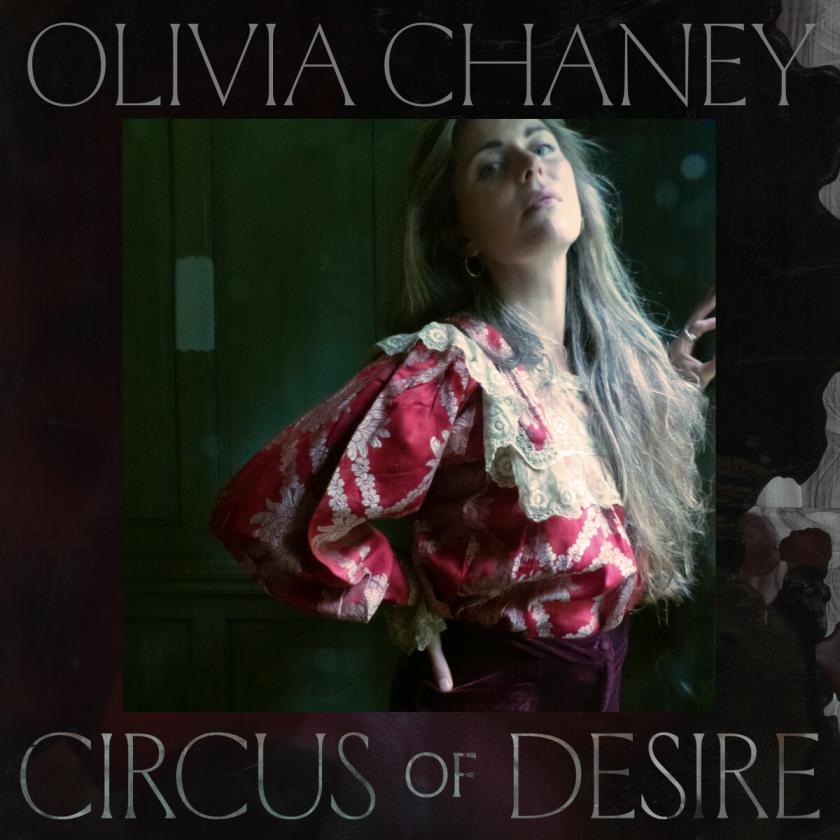

The British folk artist and singer songwriter Olivia Chaney released her third solo album this week, as we break out into springtime, and she’ll be touring sporadically around the UK over the next few months, with a showcase at London’s Union Chapel in June.

Chaney is a singular singer and songwriter with a beautiful voice and the instrumental finesse honed at the Royal Academy of Music and Aldeburgh. She released her first EP in 2010 and 2013, the year she was nominated twice, for the Horizon Award and Best Original Song, at the BBC Folk Awards (and again for Folk Singer of the Year in 2019).

Her debut album, 2015’s The Longest River encompassed Henry Purcell, her own striking originals, and traditional songs such as “The False Bride”. Her collaboration with Portland indie rockers The Decemberists as Offa Rex resulted in 2017’s Grammy-nominated Queen of Hearts set of traditional songs, encompassing the cautionary tale of “Flash Company”, intimations of mortality in “The Old Churchyard” and a superbly delicate “Willie O Winsbury” sung by a voice that could have been spun from silver.

Thomas Bartlett, the genius-level pianist, producer and member of Irish-American supergroup The Gloaming, produced her second solo set, 2018’s Shelter, with its quietly minimal arrangements on piano and guitar. Chaney and Bartlett also worked together on last year’s short set of French chanson, from the medieval ballad to Sixties pop classics. They were, she tells me, recorded over a couple of days in Chic’s old studios in New York, with Sam Amidon adding his haunting violin parts.

Now Chaney and Bartlett, again with Sam Amidon guesting, alongside a string section of Rakhi Singh and Jordan Hunt, and extra production work from Vessel, Dave Okumu and Olivia Coates, are behind Circus of Desire. Much has changed in her life since Shelter. She’s moved from London to Yorkshire, got married, is the mother of two children, and here in conversation as she prepares to release Circus of Desire, she proves to be probing, questing, revealing, and expansive in her approaches to music, to life and love and the circus of desire that comes to all out towns.

Now Chaney and Bartlett, again with Sam Amidon guesting, alongside a string section of Rakhi Singh and Jordan Hunt, and extra production work from Vessel, Dave Okumu and Olivia Coates, are behind Circus of Desire. Much has changed in her life since Shelter. She’s moved from London to Yorkshire, got married, is the mother of two children, and here in conversation as she prepares to release Circus of Desire, she proves to be probing, questing, revealing, and expansive in her approaches to music, to life and love and the circus of desire that comes to all out towns.

Tim Cumming: Tell us about working with Thomas Bartlett again

Olivia Chaney: We’d made Shelter together, and I knew I’d do this new record with him, but Covid changed the world for all of us, and mostly for the worst. I had a child during that, and then I managed to get to New York and make the record and then got back. Then I had another kid [laughs]. So a lot’s happened. I’d left London and fell in love with someone who lived in Yorkshire. And all of that fed in to the writing.

I’m not prolific but I am a writer who draws on catharsis. They’re songs drawn from experience, but there’s also an element where I try to get more universal, and the writing becomes less naval-gazing as I hopefully mature as a person.

Tell us about the album title, and title track

“Circus of Desire” has lyrics I sketched a long time ago, at the same time as another song on the album, “Bogeyman”. Sometimes you’ll sketch all kinds of things and quite consciously park an idea. Unconsciously something in you isn’t ready or knows that it needs to percolate, but it’s always there. There are so many different ideas and it’s amazing how our memories manage to hold all this stuff, because I always knew both those songs I wanted to turn into something.

Hopefully on this record there are deeply personal songs that open out to the universal. I wrote those lyrics at a very different time of my life, which was miserable and anxious. As it was when I wrote “Bogeyman”. My life has really evolved and stabilised and opened out and I’ve become a mother, and you come back to those words and they take on a different meaning for you. That’s been a beautiful part of the process of making this record.

I have quite a few songs like “Circus of Desire”. If I start trying to unpack the meaning it’s so layered, I don’t know if I’m the best person to do it. There’s a reference to Greek classical theatre, in the chorus of masks – so I was trying to frame very human conditions and potentially troubling issues, of our darkest desires, desiring things that are disruptive, and using both the circus setting and a classical Greek theatrical setting. I love how the formality of certain traditions help contain these less contained elements within us. It’s exploring the pleasure or pain thing. What is it your desire seeks – love, pain, or..? I use an almost kinky image of a man throwing a dagger – not quite S&M but sex, death, pleasure, pain. All that stuff. Then at the end of the album, there’s “I Wish” and its reference to sorrow and joy, and thinking about what is the difference between pleasure and joy and pain and sorrow, hoping that in maturity there is a little more reward and profundity in joy and sorrow, rather than in short-term pleasure seeking.

I have quite a few songs like “Circus of Desire”. If I start trying to unpack the meaning it’s so layered, I don’t know if I’m the best person to do it. There’s a reference to Greek classical theatre, in the chorus of masks – so I was trying to frame very human conditions and potentially troubling issues, of our darkest desires, desiring things that are disruptive, and using both the circus setting and a classical Greek theatrical setting. I love how the formality of certain traditions help contain these less contained elements within us. It’s exploring the pleasure or pain thing. What is it your desire seeks – love, pain, or..? I use an almost kinky image of a man throwing a dagger – not quite S&M but sex, death, pleasure, pain. All that stuff. Then at the end of the album, there’s “I Wish” and its reference to sorrow and joy, and thinking about what is the difference between pleasure and joy and pain and sorrow, hoping that in maturity there is a little more reward and profundity in joy and sorrow, rather than in short-term pleasure seeking.

So something more transformational than sensational?

Yeah, exactly. In my personal life as well I’m always interested in probing one’s own unconscious and one’s own motives for whatever it be – self sabotage, or trying to find love.

In the album’s press release, you talk of inherited trauma. Are those areas that seep into the songs and lyrics, or is it more conscious?

I find with writing that it’s both. A real privilege of being any kind of a poet or creative is that aspect of writing or making where you do something and there’s a hugely unconscious element to it but you also are consciously trying to put in ideas, and when you stand back you often see both. The unconscious element is revealed to you, so writing and making a record almost has a therapising aspect. There’s such an arc to it all.

Although a lot of those ideas are conscious, as many of us are working through what we think our traumas are, familial, personal, inherited, and I feel like I have my fair share of all three, as you go through life trying to work through them, and as a mother, that really changes things. There’s an interesting paper by an analyst called Ghosts in the Nursery, that says as a mother you are constantly met by your own childhood, on a minute-by-minute basis, and it can be good and bad. Your memory is constantly being probed, and your unconscious is being jostled as you learn to look after your own child.

The song “Calliope” is about your eldest daughter?

Yes, a homage to her. It is such an earth-shattering thing, becoming a mother and a parent. I wanted to write something quite pure and joyful, which again is a new experience for me as I tend to write from these positions about inherited trauma… I remember thinking, how am I going to write from a place that’s not a place of pain and suffering and angst – that’s all I’ve known before [laughs]. Even in songs like “Galop”, exploring darker themes, there are redemptive elements of celebration as well.

“Galop” is the most overtly dark one, and one of my favourites on the album. Because I think a life unexamined is not a life worth living, and self-knowledge is the key to survival, if not to a joyful and more fulfilling life, even if a song is seemingly dark, so long as it is exploratory and questioning and probing, that to me is not straightforwardly sad or depressing.

Tell us about the recording the album

It was one concentrated, joyful block. We stayed in a late painter-sculptor’s house in Chelsea, that’s like a museum, and the lady still managing the estate let us live in the basement. Thomas and I were making the songs for three weeks or so, and we were producing as we went along,. It’s very painterly, how Thomas works. Some pop records are very compartmentalised in how they’re made, but that’s not how he works.

We speak such a similar language, musically and intellectually. The way he works is very psychoanalytic. He’s in analysis himself. He approaches working with everyone in that way, but if he knows you’re interested in that, he’ll go all the way into it.

He has films playing all the time, silently, on a screen. At first I thought, oh God, but he kind of laughed and didn’t turn it off. It really teased something out, it really helped me switch off that sometimes unhelpful conscious, analytic part of your brain. The part that arguable blocks your unconscious. It was really, really interesting. I don’t even know what some of the films were. It creates a very strange dreamlike quality. The song “Mirror Mirror” I hadn’t finished writing, and I’d never have dared work like this in the past – writing on the hoof. But I really embraced sloughing that off. I had the title and the beginning, and the music was there., and as I was finishing the lyrics, Tarkovsky’s The Mirror was playing!

He has films playing all the time, silently, on a screen. At first I thought, oh God, but he kind of laughed and didn’t turn it off. It really teased something out, it really helped me switch off that sometimes unhelpful conscious, analytic part of your brain. The part that arguable blocks your unconscious. It was really, really interesting. I don’t even know what some of the films were. It creates a very strange dreamlike quality. The song “Mirror Mirror” I hadn’t finished writing, and I’d never have dared work like this in the past – writing on the hoof. But I really embraced sloughing that off. I had the title and the beginning, and the music was there., and as I was finishing the lyrics, Tarkovsky’s The Mirror was playing!

The album has a strong family theme, with a poem of your grandfather’s set to music on “Zero Sum” – and “To the Lighthouse” is about your sister

And a song about my daughter. So it is quite family-themed, almost representing three generations. When I set “Zero Sum” to music, I didn’t know he would pass away before the record came out. My grandfather was a mathematician by trade, and when he retired he became a poet, and when my sister’s kids were born he started writing children’s poems with many hidden lessons in them. They appealed to me for their seeming simplicity, and that’s something I celebrate in my writing more.

My grandfather was a big influence on me artistically, and “Zero Sum” was a good excuse to explore that aspect of music I love – the minimalist composers I listen to – and to bring in a bit of my extended voice technique. Sometimes when you set someone else’s text it gives you license to do things you might not allow yourself to do to your own writing.

Finally, will Offa Rex ever raise its head again?

I’d absolutely love to, and I do have some little plans up my sleeve, but I have to say – maybe I’ll leave I there – but I have got some plans. It might be Offa Rex Part 2 with a different band. I would love to try to get Richard Thompson on board. So yeah, that’s definitely something I’d like to do next.

Add comment