The Western image of manga comes from the thick volumes of knicker-flashing schoolgirls and lurid s.f. teenage boys pore over, and the anime (cartoon films) which adapt them. Singaporean director Eric Khoo’s animated adaptation of five stories by Yoshihiro Tatsumi, framed by details from his graphic autobiography A Drifting Life, reveals a radically different medium. As a young man proud of an art form which was being attacked for corrupting postwar Japanese youth, the now 76-year-old Tatsumi coined a new term for adult comics, gekiga (dramatic pictures), in 1957. It took until the 1970s for his crusade to be accepted, a steadfast commitment clear in the work Khoo presents. None of Tatsumi’s work has been adapted for the cinema before. It’s strong meat.

The 1970s stories here are almost unhinged in their driven potency. “Hell” follows a Japanese military photographer through shattered Hiroshima (pictured above). The photo he takes of an ash-shadow on a wall, all that remains of a son lovingly massaging his mother’s back, becomes his route to fame, national honour and fortune. Statues are erected of his image, foreign tours arranged. But the wheezing, masked figure haunting Hiroshima’s ruins would like a word...

The 1970s stories here are almost unhinged in their driven potency. “Hell” follows a Japanese military photographer through shattered Hiroshima (pictured above). The photo he takes of an ash-shadow on a wall, all that remains of a son lovingly massaging his mother’s back, becomes his route to fame, national honour and fortune. Statues are erected of his image, foreign tours arranged. But the wheezing, masked figure haunting Hiroshima’s ruins would like a word...

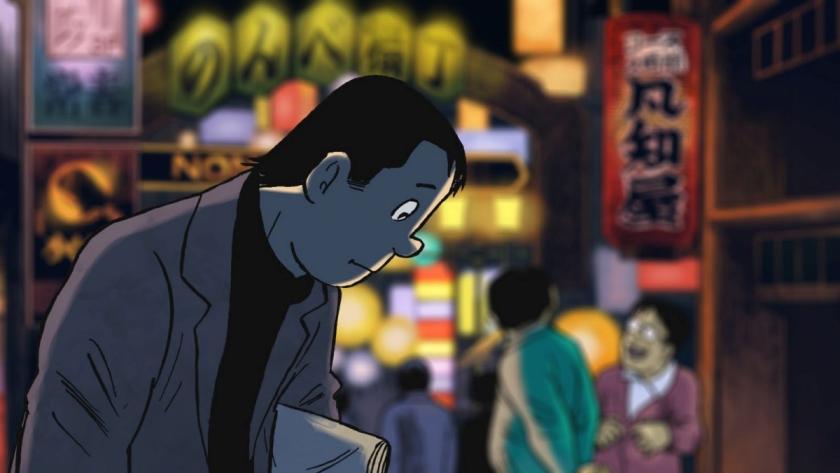

“Good-bye” (pictured below) similarly pokes in the guts of Japan’s immediate postwar humiliation, as a woman services hulking GIs in her shack, and her father, still in the defeated Imperial Army’s uniform, hangs around for scraps of cash from her table. Both stay drunk, till the daughter decides on an act of such horrific transgression, it cancels every previous shame. The other, equally strong stories deal with sweating, overwhelmed salarymen, desperate for sex or some sort of way out from a regimented society, but doomed in imaginatively twisted ways not to find it.

The animated versions of Tatsumi’s black-and-white panels have a jerky, brutal energy, gouting red blood when his protagonists stumble into sudden moments of full, screaming horror. The Western equivalent would be the 1950s EC horror and war comics, which caught so much of America’s postwar psyche in grimly elegant panels. The regulation twist endings of Tales from the Crypt and the like were risqué enough for the comics to be banned, after a public outcry at their effect on kids in the era of the McCarthy witch-hunt, neutering the mainstream art form in the US for decades. But they can’t compare with the genuinely adult themes Tatsumi powers his pulp fiction with, or the hysterical national and personal truths they fling at the viewer. These are not distanced literary works, they spring from somewhere more chaotic and hot-blooded, just about corralled by Tatsumi’s artistic intelligence. It’s no surprise to learn that postwar Japan’s most mercilessly iconoclastic writer, Yukio Mishima, was a fan. Khoo and animation overseer Phil Mitchell give them all rough life.

The animated versions of Tatsumi’s black-and-white panels have a jerky, brutal energy, gouting red blood when his protagonists stumble into sudden moments of full, screaming horror. The Western equivalent would be the 1950s EC horror and war comics, which caught so much of America’s postwar psyche in grimly elegant panels. The regulation twist endings of Tales from the Crypt and the like were risqué enough for the comics to be banned, after a public outcry at their effect on kids in the era of the McCarthy witch-hunt, neutering the mainstream art form in the US for decades. But they can’t compare with the genuinely adult themes Tatsumi powers his pulp fiction with, or the hysterical national and personal truths they fling at the viewer. These are not distanced literary works, they spring from somewhere more chaotic and hot-blooded, just about corralled by Tatsumi’s artistic intelligence. It’s no surprise to learn that postwar Japan’s most mercilessly iconoclastic writer, Yukio Mishima, was a fan. Khoo and animation overseer Phil Mitchell give them all rough life.

Tatsumi’s autobiography in-between the stories can’t, of course, hope to compete in interest, and the artist’s insights into his work verge on the trite. But his struggles to support his parents as their marriage drifts apart, the rivalry of his sickly brother, and the fellowship he eventually feels with other young manga artists making their way in the 1950s are an instructive context. They are rendered in painterly colour, in contrast to his imagination’s harsh black-and-white printed world. His real triumph isn’t any individual story, but an image of a Tokyo bookshop, neatly divided into novels and manga, with its gekiga section behind a cool glass divide. This film should send us to those shelves, where an unguessed-at Japan waits.

- Tatsumi is on release from Friday, 13 January

Watch the trailer for Tatsumi

Add comment