Kantemir Balagov’s second feature announces the arrival of a major new talent in arthouse cinema. Made by the Russian director when he was just 27, and premiered at Cannes last year, where it won in the “Un Certain Regard” strand, Beanpole approaches its bleak aftermath-of-war story with all the practised subtlety of an established auteur while delivering an emotional impact that is empathetic and shocking in equal measure.

Set in 1945 in Leningrad, months after the end of the Great Patriotic War at a time when any elation of victory has given way to an understanding that the future will be one of harsh survival, the film’s aesthetic somehow foregrounds deprivation: Balagov’s script, co-written with Alexander Terekhov, is notably spare, and the film’s only music diegetic, an effect that’s enhanced by nuanced sound design.

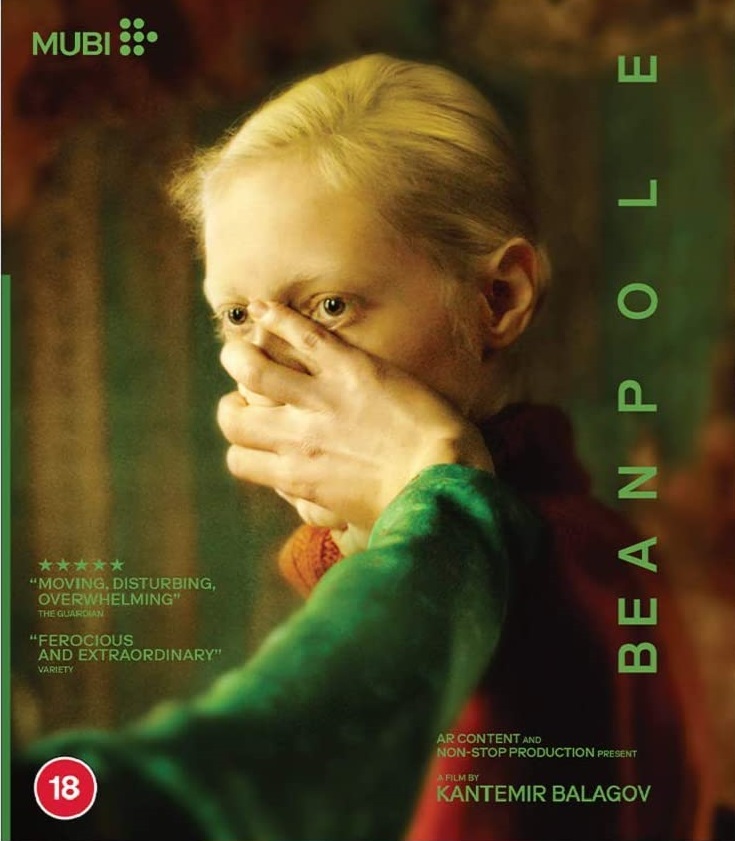

It’s a stark background for the film’s remarkable central pairing, Viktoria Miroshnichenko and Vasilisa Perelygina as Iya and Masha, two friends whose wartime experience has brought their lives as close together as is possible to imagine (Balagov doesn’t hurry to reveal just what it is that links them so closely). It’s an unlikely bond that’s somehow enhanced by their physical differences – Iya is the “beanpole” of the title, tall to the extent of ungainliness (a sense that’s there more particulalry in the film’s Russian title, “Dylda”). Miroshnichenko has the face of a young Tilda Swinton, with an extra Slavic luminous innocence, and she’s often abstracted, while as the slighter, shorter, more humorous Masha Perelygina is always engaged and purposeful. Iya’s awkwardness is enhanced by the periodic semi-paralytic fits that are a legacy of wartime trauma, which in turn bring about the film’s most desperate scene (it's conveyed so laconically by the director that viewers may initially barely register what’s happening, until the crushing impact hits home).

It’s a stark background for the film’s remarkable central pairing, Viktoria Miroshnichenko and Vasilisa Perelygina as Iya and Masha, two friends whose wartime experience has brought their lives as close together as is possible to imagine (Balagov doesn’t hurry to reveal just what it is that links them so closely). It’s an unlikely bond that’s somehow enhanced by their physical differences – Iya is the “beanpole” of the title, tall to the extent of ungainliness (a sense that’s there more particulalry in the film’s Russian title, “Dylda”). Miroshnichenko has the face of a young Tilda Swinton, with an extra Slavic luminous innocence, and she’s often abstracted, while as the slighter, shorter, more humorous Masha Perelygina is always engaged and purposeful. Iya’s awkwardness is enhanced by the periodic semi-paralytic fits that are a legacy of wartime trauma, which in turn bring about the film’s most desperate scene (it's conveyed so laconically by the director that viewers may initially barely register what’s happening, until the crushing impact hits home).

Balagov sets the pattern of these two womens’ lives between the war veterans’ hospital where they work and the communal apartment that is Iya’s home (echoes there, surely, of Alexei German’s Khrustalyov, My Car! in the chaotic, polyphonic interiors). It’s a world that juxtaposes life and death in every sense, new beginnings – evident in the growing desperation with which Masha sets about conceiving a child – set off against literal endings, seen most starkly when Iya accedes to the pleas of a patient, paralysed from the neck down, to terminate his life.

There’s an extreme, almost bruising tenderness in the way that Balagov and his cast capture such relationships. The bleakness here is never wiful – something you can't always say of such new Russian arthouse fare – and Beanpole offers an element of amelioration of its darkness in the range of visual textures with which cinematographer Ksenia Sereda makes her mark (younger than her director, she delivers work here that’s as fully realised as anything any more experienced DP might come up with). Balagov went back on his initial intention to make the film in black and white, creating instead a visual palette that’s dominated by greens, reds and mustard-yellows, hues that are always restrained and somehow fragile, and striking in their almost painterly beauty; some scenes, one in a womens' bathhouse particulalry, infuse a feel of candlelight into otherwise harsh interiors, suggesting nothing less than the Dutch Old Masters. In an elusive but engrossing way, it's kind of visual reprieve.

This MUBI release comes without extras, and it’s worth tracking down what Balagov has said about his film, his appearances at the New York Film Festival 2019 and at Film Forum (audio only) among the best places to start. Significantly, he cites the starting-point for the film as being his reading Svetlana Alexievich’s 1985 The Unwomanly Face of War, in which the Belarusian Nobel laureate recorded oral documentary testament from female WWII survivors. Balagov has studied under the tutelage of Russian master Alexander Sokurov, who, we learn, typically exhorts his pupils to study literature as much as cinema (thus, that quintessential Russian writer Andrei Platonov is another influence acknowledged by the young director). But any such references ultimately do little to explain the concentrated intensity, the sheer maturity that Balagov has achieved here: his is a career to be followed with urgent interest.

Add comment