Diana Vishneva's last solo show was called Beauty in Motion, a pretty safe bet under the Trade Descriptions Act, since the Mariinsky prima ballerina and ABT guest star is unfailingly, remarkably beautiful. The new one, which came to the Coliseum last night 18 months after its première in California, rejoices in the much more ambiguous title of On the Edge. On the edge of what? Nervous breakdown? Retirement? Being less than beautiful?

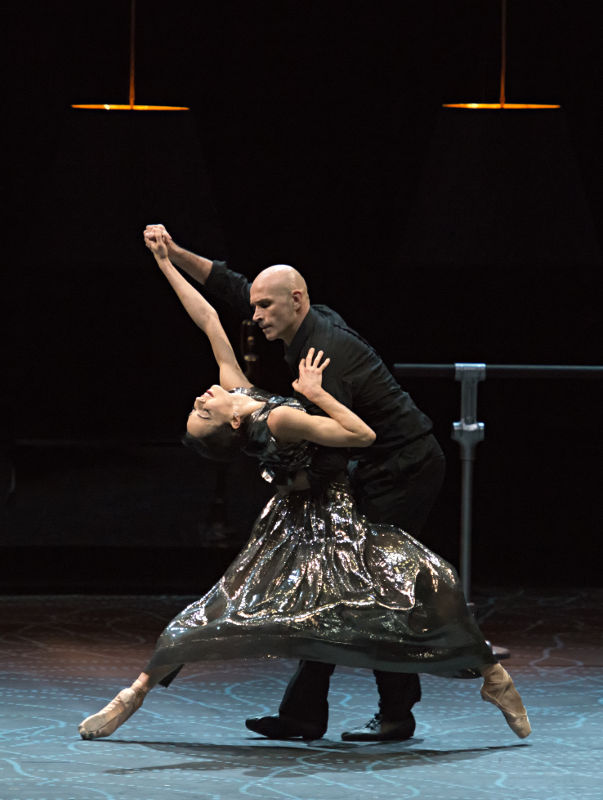

Having seen the show, I'm no more enlightened. Switch, by Jean-Christophe Maillot, Director of Les Ballets de Monte Carlo, is an odd beast, a psychological drama with interesting characters, whose interactions I just could not get my head round. There's a couple – Gaëtan Morlotti and Bernice Coppieters – and they're not dainty ballet ingénues but mature adults, with an apparently mature relationship, the broad-shouldered Coppieters particularly striking as a grown-up, confident, "normal" woman, a type of female character not often seen in dance. Then there's Diana Vishneva, who stalks on with megastar attitude billowing, the ripples she makes in the air nearly as visible as the stunning silver crêpe Karl Lagerfeld dress that shimmers around her (pictured below right, with Morlotti). Its loose folds and lunar colour point straight to Vishneva's namesake, the Roman virgin goddess of the hunt, Diana.

Is she supposed to be a real person – a dancer? The alter ego of Coppieters' character? An allegory of Art? Whoever she is, she proceeds to have a complex relationship with the couple, seeming to demand care, adoration, and loyalty from both of them while driving them apart. But she has limited success; at the end she drags a ballet barre across stage like a ball and chain, then, stripping to her leotard, contorts herself over and under it, while the couple echo her contortions in the background – on each other's laps. There's a suggestion at the end that Vishneva's character decides their canoodling looks more fun than being a virgin goddess of Art, so she ties her shoes to the barre like two totemic sacrifices.

Is she supposed to be a real person – a dancer? The alter ego of Coppieters' character? An allegory of Art? Whoever she is, she proceeds to have a complex relationship with the couple, seeming to demand care, adoration, and loyalty from both of them while driving them apart. But she has limited success; at the end she drags a ballet barre across stage like a ball and chain, then, stripping to her leotard, contorts herself over and under it, while the couple echo her contortions in the background – on each other's laps. There's a suggestion at the end that Vishneva's character decides their canoodling looks more fun than being a virgin goddess of Art, so she ties her shoes to the barre like two totemic sacrifices.

There is lots of interesting movement in Switch – Maillot has easy command of a naturalistic blend of ballet, contemporary and expressionist, which Morlotti and Coppieters do as easily as one would expect from top members of the choreographer's own company; and of course, Vishneva makes anything look fabulous, sashaying around in that dress as if she herself was made in a couture atelier. But the emotions are cartoonishly awkward (head-clutching!), as is the music, an ill-seamed, recorded mash-up of bits from Danny Elfman's back catalogue which is heavy on "ominous" strings and brass. It's hard to tell whether it's a bad concept being executed well, or vice versa. Either way, you couldn't call it an unqualified success.

Carolyn Carlson's solo for Vishneva, Woman in a Room, plays a dangerous game by inviting comparison with Mats Ek's Bye for Sylvie Guillem, a joy of a piece in which one woman remembers the course of her life. Carlson's piece similarly has Vishneva exploring a range of characters, behaviours and costumes, and even uses a black and white video screen like Bye, though this one mostly just projects a softly rustling tree (pictured left). The tree and the whistling flute/viola soundtrack suggested Scandinvia to me, but Vishneva is clearly not going to be one of the petrified female figures of Vilhelm Hammershøi's interiors; the bright downward light that picks her out against a dark background puts her much more in the visual world of Dutch Golden Age painting and the contained turbulence of its women.

Carolyn Carlson's solo for Vishneva, Woman in a Room, plays a dangerous game by inviting comparison with Mats Ek's Bye for Sylvie Guillem, a joy of a piece in which one woman remembers the course of her life. Carlson's piece similarly has Vishneva exploring a range of characters, behaviours and costumes, and even uses a black and white video screen like Bye, though this one mostly just projects a softly rustling tree (pictured left). The tree and the whistling flute/viola soundtrack suggested Scandinvia to me, but Vishneva is clearly not going to be one of the petrified female figures of Vilhelm Hammershøi's interiors; the bright downward light that picks her out against a dark background puts her much more in the visual world of Dutch Golden Age painting and the contained turbulence of its women.

Not that there's anything contained about the turbulence Vishneva actually conveys: she's all over the place, writhing, grimacing and frantically kicking her legs – until the mood changes and she dons a little see-through chiffon dress and high heels to mince about in ambivalent, but rather funny, coquetry. That's the piece's most successful mode, returned to near the end for a killer sequence which recasts the old adage about making lemonade: obviously if you're Diana Vishneva, when life gives you lemons you just chop the shit out of those little bastards, then serve them to the audience.

The piece is inspired by the work of the legendary Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky. I'm not familiar enough with his work to tell if Woman in a Room captures some of his mood, but it certainly doesn't live up to his visuals: while the set and lighting are striking, the actual dance is unmemorable at best, and at worst makes even the heavenly Vishneva look rather awkward. The score is another mash-up job with bits of Giovanni Sollima and René Aubry, like a less twee version of the Amélie soundtrack.

A dancer of Vishneva's calibre doing anything is usually worth a look (even more so when dressed by Karl Lagerfeld) and the two pieces in On the Edge are not without interest. But, with their convoluted psychodrama, neither are they likely to become the signature personal vehicles for Vishneva that Bye became for Guillem – more's the pity.

- On the Edge continues at the London Coliseum 16, 18 April

Add comment