Lucian Freud was never an entirely willing subject, but his remark to William Feaver that his biography would be “the first funny art book”, now seems more astute than throwaway. It is entertaining, certainly, but it is also a singular mixture of biography and autobiography, answering to neither, and yet exceeding the bounds of both, while presenting a collaborative effort that “book” seems hardly adequate to cover.

This first volume of two takes us to 1968 and its physical heft reflects the scale of the project, which began in 1973 when the critic and author Wiliam Feaver met Freud to interview him for the Sunday Times Magazine. It turned out that Feaver was not the first writer to have been given the assignment, but where his predecessor had been sent away empty handed, Feaver not only got his interview, but struck up a friendship that would last until Freud’s death in 2011.

Though Freud had no telephone until the late 1970s - and even then Feaver was never vouchsafed his number – this was quickly established as the principle means of communication, with Freud presumably begging friends and acquaintances for the use of their phone. Eventually, their conversations took place almost daily, with Feaver’s notes forming the basis of the book.

Though Freud had no telephone until the late 1970s - and even then Feaver was never vouchsafed his number – this was quickly established as the principle means of communication, with Freud presumably begging friends and acquaintances for the use of their phone. Eventually, their conversations took place almost daily, with Feaver’s notes forming the basis of the book.

The book retains a conversational tone, and the narrative is propelled along by a steady flow of anecdote and gossip, and surprisingly little direct discussion of painting (Pictured above right: Freud and Brendan Behan in Dublin, 1953). Freud’s own words provide a solid enough scaffold, but they give the book the easy appeal of collected letters, which can be dipped in and out of just as well as read sequentially.

The strength of Feaver’s primary source means that often his own words amount to little more than connective tissue. Curiously, though the book evokes very well the intimacy between the two friends, the dominance of Freud’s voice is total, with Feaver himself suspending judgement as he retreats behind the authority of his subject’s own words.

Difficult territory has to be negotiated regardless, and Freud’s notorious selfishness, and casual treatment of women comes up fairly regularly, reflecting, presumably, the natural bias of his conversation. When things get sticky, Feaver all but disappears from view, and the few interjections that he does make seem, consequently, all the more significant.

Freud’s former lover Ann Dunn talks of his controlling nature with devastating understatement, saying that “if one had perhaps been victimised in one’s childhood Lucian was quite productive at bringing that out”. But the force is taken out of her remark by Feaver, who prefaces Dunn’s judgement with a softening sentence, framing his bullying as “a perhaps compulsive desire to have the upper hand.”

This is a book that only exists because of a constant and deep friendshipOne senses in such moments a tension between the author’s loyalty to his friend and his desire to give a balanced account. Freud was evidently resistant to the idea of a biography, preferring instead to refer to Feaver’s book as “a novel” that would appear after his death. It’s intriguing to imagine that the absence of analyis is an inevitable consequence of Freud’s immediate ancestry, but one never gets the sense of Feaver really tackling his subject on anything.

If it were a run of the mill biography, this would be a fatal flaw. But this is a book that only exists because of a constant and deep friendship, and as such it is a record of far more than the life of an individual artist. It tells of Freud, but it tells too of life among a particular milieu in the first half of the 20th century. It probably tells us quite a lot about the author, and it certainly tells us about the peculiar relationship between a writer and an artist, a biographer and his subject.

Published almost concurrently by Prestel, the Lucian Freud Herbarium is no less revealing, bringing together the artist's paintings and drawings of plants. Plants are often a prominent feature of Freud's portraits - who could forget the monstrously present yucca plant in Interior in Paddington, 1951? But the most interesting works in this book are essentially studies, like the Still-life with Aloe, an oil painting from 1949. Here a herring lies next to an uprooted aloe vera plant: each tinged with green, the formal similarities between them are astonishing. And the herring is so much more dead than the plant, which raises itself slightly in a final bid for life. It's a painting that allows us to access some insight into the quality and nature of Lucian Freud's looking, and through it to find pathos and subtlety in his portraits.

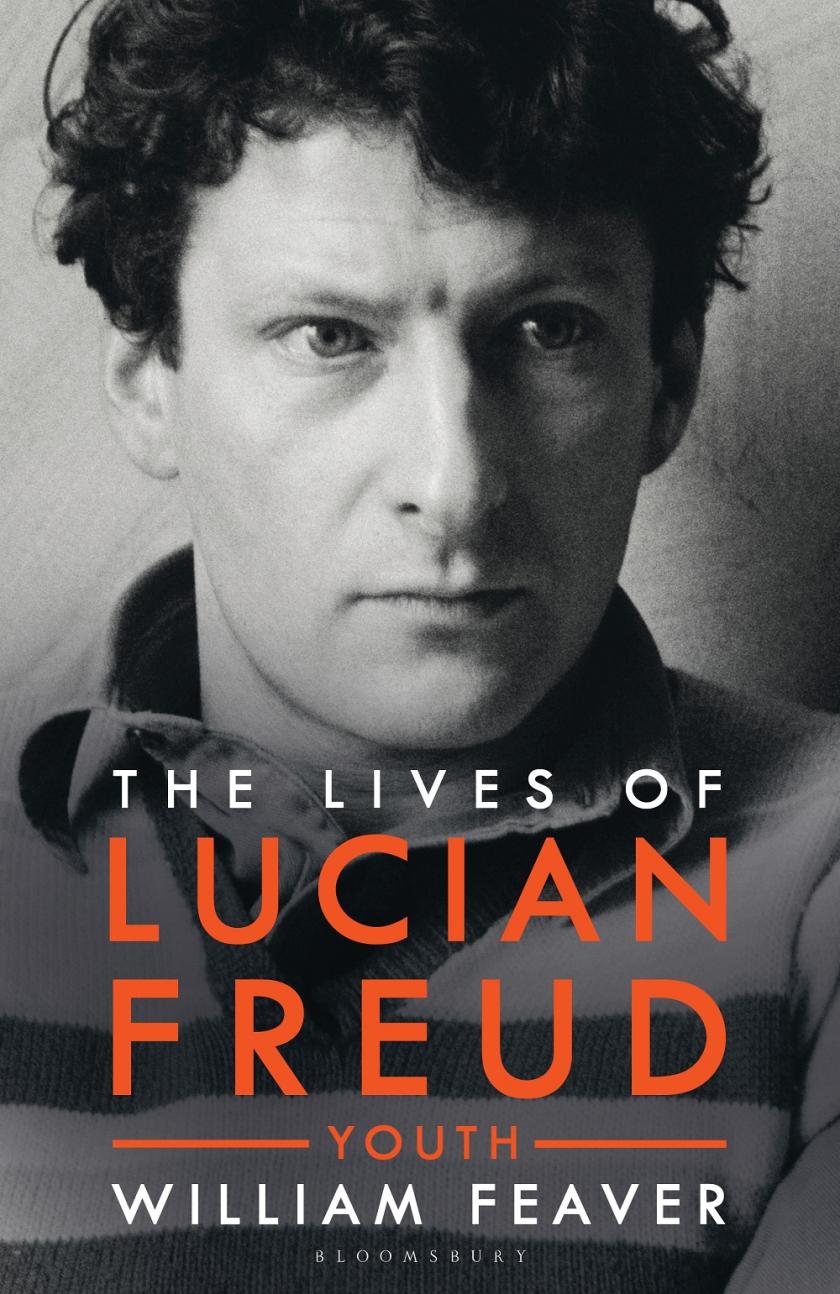

- The Lives of Lucian Freud: Youth 1922-1968 by William Feaver (Bloomsbury Publishing £35)

- Lucian Freud Herbarium by Giovanni Aloi (Prestel £39)

Add comment