Some years after Chronicles (2004) a book that broke moulds and delighted with its originality, and as with albums that often came with changes of attitude and style, Bob Dylan's "philosophy" comes as something of a surprise.

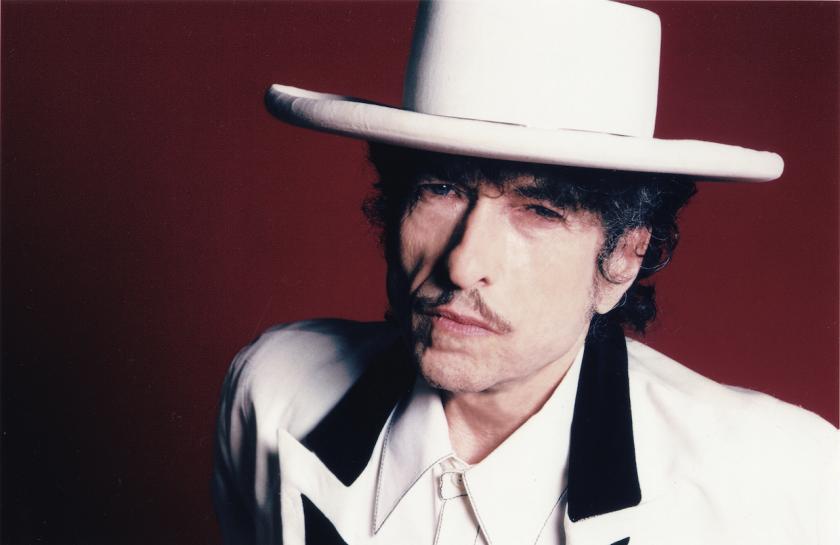

This is a man who contains multitudes, a man who plays with masks, a man who has never ceased to surprise us. He is a man who would be an outlaw, though has always served somebody; the man who sold his soul to Victoria’s Secret, denounced the brutal murder of Hattie Carroll, and bamboozled most of his fans when he became a born-again Christian. True to form, he offers us a strange and wonderful new book, at times witty and original, and at others swamped in homespun philosophy. With each chosen song, he freely associates, writing about the voice behind the lyrics and the content of the song, in a series of non-linear reflections that explore his many and often paradoxical perspectives on America. Making America great again, for the prodigy poet from Minnesota, will be done with plenty of boogie and the sexual energy at the heart of rock'n'roll.

The songs run from Elvis Costello’s “Pump it Up” , a punkish affirmation of male power, to Dean Martin’s crooning on “Blue Moon”; a triumph of earthy rockabilly from the little-known Sun Studios artist Sonny Burgess to Domenico Modugno’s “Volare”; or the Temptations' blistering state-of-the-world alert “Ball of Confusion”. The last is praised as a quintessential protest song, a remarkable and typically generous comment from the man who made the genre so very much his own. Dylan is very present throughout, he is talking to us, and wandering through the landscape of American dreams and realities, using the medium of popular song to illuminate mostly familiar history and culture in his own very personal way.

Popular song, for Dylan, is all about projection, a theatre of archetypes, rich and varied, that excite and nourish those who listen: lovers, criminals, heroes, prophets – the downtrodden as well as the free spirits, a multifaceted cast of human possibilities, whether brought to light by Elvis, Bobby Darin, The Grateful Dead, Nina Simone, Willie Nelson, Perry Como, Jimmy Reed or one of the other singers he evokes so vividly. This is a very idiosyncratic book as you would expect from an artist who has distinguished himself from the very start as an unpredictable trickster figure who challenges his audience time and time again.

This is no ordinary book of philosophy – unless you would accept that the freewheeling improvisation of bar-room chatter amounts to a kind of spontaneous philosophising. Much of it feels as if it might have been thrown off without afterthought, a kind of poetic stream of consciousness that draws on Dylan’s adventure with the idea of America, its myths from the road trip to the massacre of the First Nations, from the notion of making heaven on earth to the worst excesses of capitalism, moments of spiritual ecstasy to horrors of war.

This is no ordinary book of philosophy – unless you would accept that the freewheeling improvisation of bar-room chatter amounts to a kind of spontaneous philosophising. Much of it feels as if it might have been thrown off without afterthought, a kind of poetic stream of consciousness that draws on Dylan’s adventure with the idea of America, its myths from the road trip to the massacre of the First Nations, from the notion of making heaven on earth to the worst excesses of capitalism, moments of spiritual ecstasy to horrors of war.

He is at his best when his passion is aroused – that passion and fury which emerge sometimes on stage, as in some of the live recordings of “Solid Rock” on his gospel tours, or during the extraordinary performance I saw him give in Bournemouth a few weeks ago. There has always been a preacher in Bob Dylan, as well as a rock'n'roll doctor, and, at his best, he dispenses wisdom with almost shamanic force. In the new book, there are, among some more pedestrian and sometimes mystifying passages, moments that summon that same flame, combining brilliance with emotion.

Johnny Paycheck’s “Old Violin” – a fabulous track I didn’t know, but am delighted to do so now – celebrates a former convict’s deeply felt exploration of ageing, a theme which has enriched much of Dylan’s work since Time Out of Mind (1997). Not only are the singer’s interpretation and the mournful pedal steel incomparably moving, but he writes about it in a way that is totally attuned to the track. He is good at evoking the essence of a song and its singer. Edwin Starr’s “War” provides Dylan with an opportunity to riff on the subject of war and the crimes associated with it. What is remarkable, though, is the difference between what he writes here, and the accusatory fury of ”Masters of War” from his angry youth. Now, with the wisdom of old age, he asks us to recognise that we too are as guilty, not least if we are complicit with the masquerade of democracy: “If we want to see a war criminal, all we have to do is look in the mirror.”

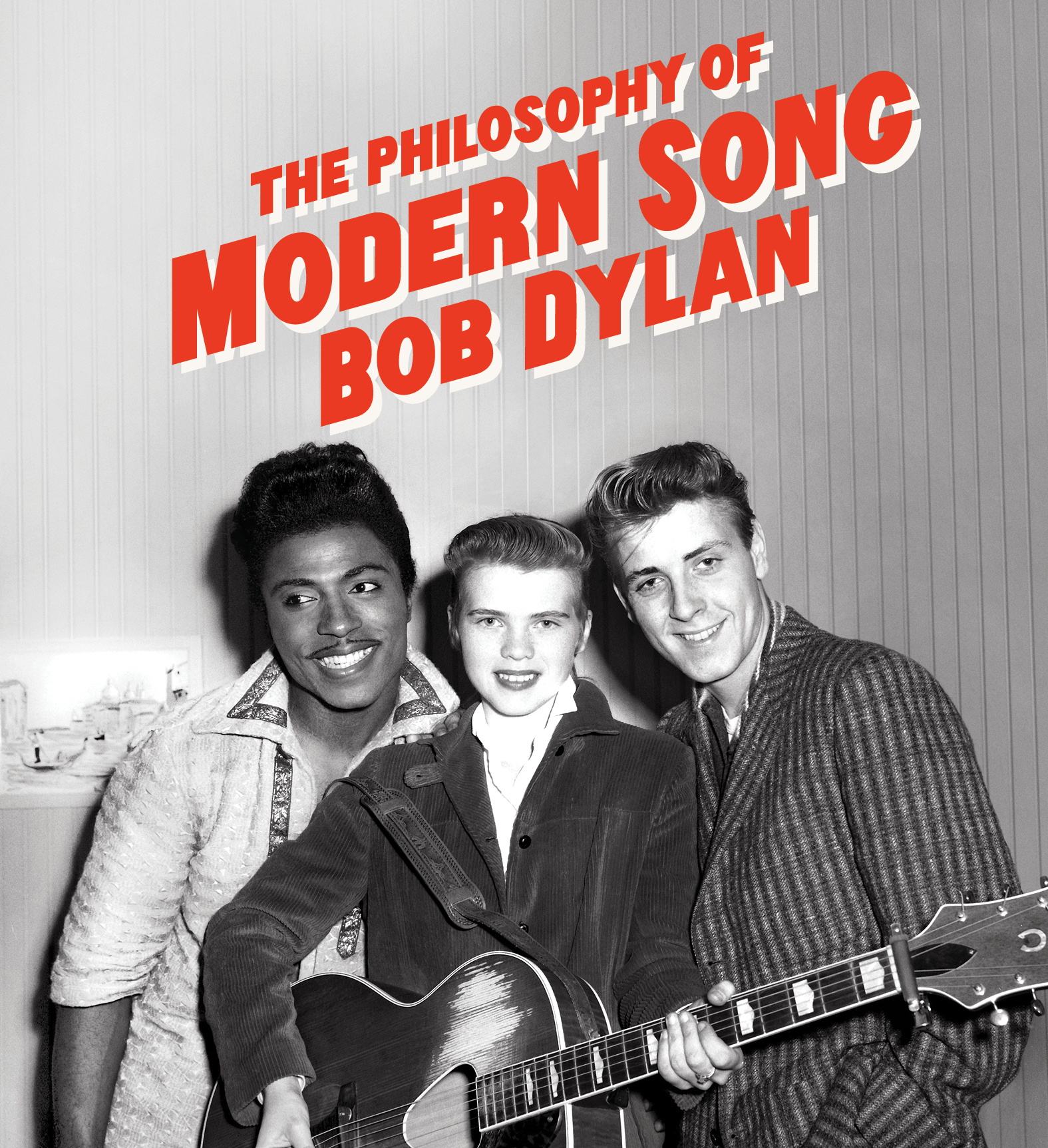

The book is designed a little like a magazine – it makes for a fun non-linear read, one that you can dip in and out of. The illustrations are well-chosen, often quite surprising, as the 19th century print of a whale hunt that accompanies the text on Bobby Darin’s "Beyond the Sea", an adaptation of Charles Trénet’s French chanson classic “La Mer”, or an enticingly smiling dancing girl with a head-dress piled high with plastic fruit alongside a lively deconstruction of Little Richard’s uproarious hymn to drag and queerness, “Tutti Frutti”. Clever juxtapositions of images complement the "philosophical" ramblings that rooted in a nation’s popular culture.

Unless you're a nerdy encyclopaedia of song, the only way to read this book is with the means to sample each song before or after having read about it. There's something to be said for buying the audiobook, although this curiously doesn’t include the songs themselves, so I found myself toing and froing between Audible and Spotify. It actually works remarkably well. Dylan reads the more subjective material himself, while a cast of actors and actresses, vehicles for the personae Dylan wishes to evoke, take care of the rest: Jeff Bridges's well-worn senior growl is perfect, for country classics such as Hank Williams’s “Your Cheatin’ Heart” and Waylon Jennings “I’ve Always been Crazy”, Helen Mirren’s Anglo tones for Costello’s macho posturing in “Pump it Up” and Sinatra’s “Strangers in the Night”, another outsider song as Dylan, confirmed devotee of "Ol' Blue Eyes", readily points out; Steve Buscemi’s seedy cool for Warren Zevon’s “Dirty Life and Times” in which Dylan launches into paroxysms of verbal daring, as he tells the narrator of Zevon's song, “You’re the tomcat with the stuff penis who pisses gold wine, and brings ripples of excitement to stodgy old lives.”

Unless you're a nerdy encyclopaedia of song, the only way to read this book is with the means to sample each song before or after having read about it. There's something to be said for buying the audiobook, although this curiously doesn’t include the songs themselves, so I found myself toing and froing between Audible and Spotify. It actually works remarkably well. Dylan reads the more subjective material himself, while a cast of actors and actresses, vehicles for the personae Dylan wishes to evoke, take care of the rest: Jeff Bridges's well-worn senior growl is perfect, for country classics such as Hank Williams’s “Your Cheatin’ Heart” and Waylon Jennings “I’ve Always been Crazy”, Helen Mirren’s Anglo tones for Costello’s macho posturing in “Pump it Up” and Sinatra’s “Strangers in the Night”, another outsider song as Dylan, confirmed devotee of "Ol' Blue Eyes", readily points out; Steve Buscemi’s seedy cool for Warren Zevon’s “Dirty Life and Times” in which Dylan launches into paroxysms of verbal daring, as he tells the narrator of Zevon's song, “You’re the tomcat with the stuff penis who pisses gold wine, and brings ripples of excitement to stodgy old lives.”

Dylan’s own voice has been recorded and produced with a good deal of reverb, as if he were speaking prematurely – from beyond the grave. The other voices are close mic’ed and intimate, while the author’s is distant, suggesting the aural equivalent of black and white, while the actors are in living colour. Is this an affectation or irony – as with a title that plays with the notion of "philosophy"? You never know with Dylan: his most sincere moments, as with many performing artists, come when he is masked. He can so easily move from being a poet to seemingly taking us for an ironic ride.

The book is far from perfect, rather like Dylan’s recorded work. There are moments of discovery: he picks out songs that are not that well-known, for instance the exquisite pop of ”Poison Love” by Johnny and Jack, as well as moments of insight. The essay evoked by the half-spoken song “Doesn’t Hurt Anymore” by First Nation singer John Trudell, whose wife and kids were burnt alive in the fire-bombing of his home, is electric in its almost biblical anger. Dylan is very much on the side of those who know that America's promised land was built on genocide.

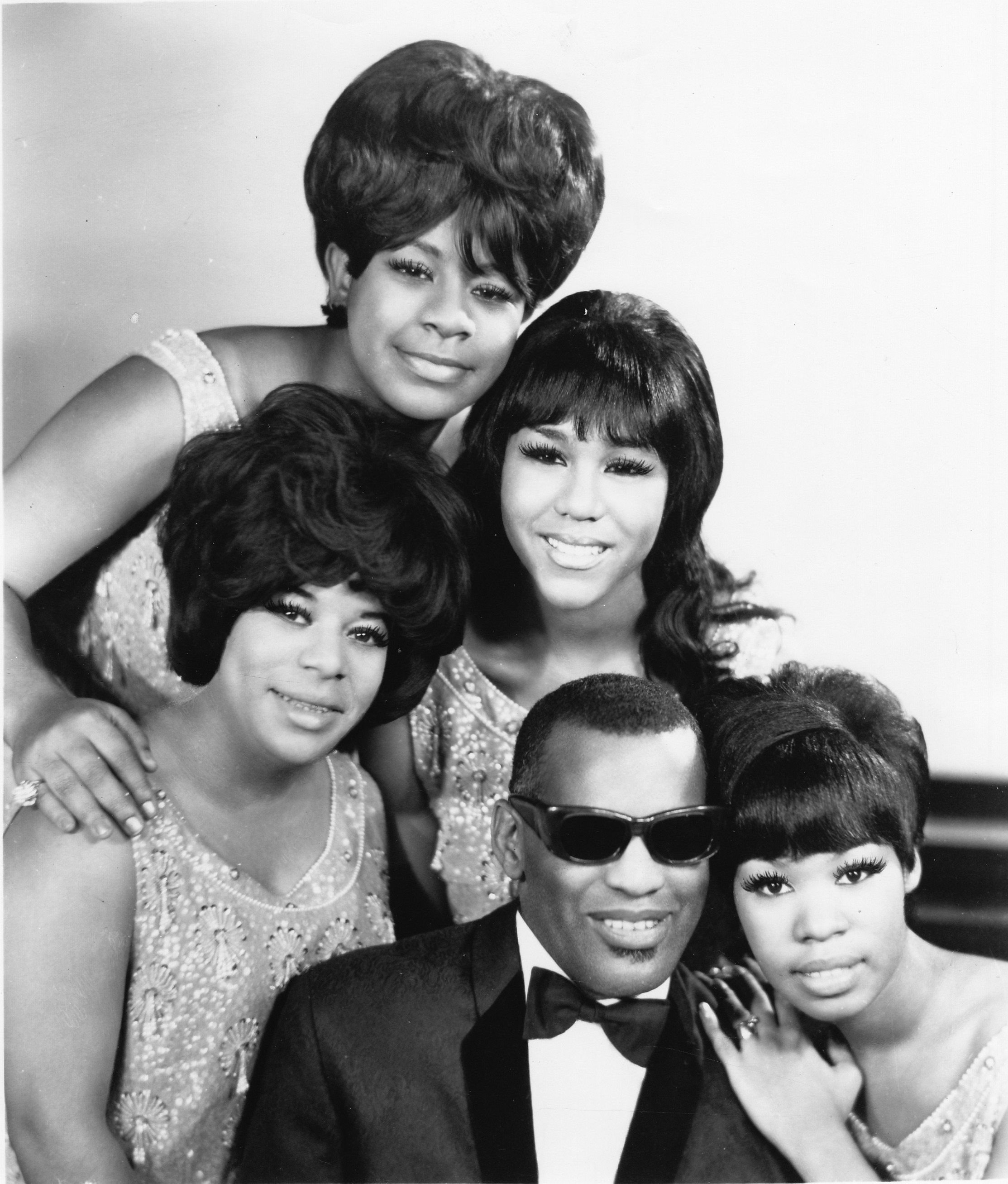

Some of the essays are lengthy and discursive, and others do little more than celebrate through poetic paraphrase, as in the write-up of "I've Got a Woman" by Ray Charles (pictured above, with the Raelets, courtesy of Gilles Pétard collection), described as if Dylan himself were the man driving back to the woman he lusts for and loves. His learned fan's devotion to musical detail is revealed when he mentions David "Fathead" Newman's concise but fiery tenor break, a brief but eloquent sermon about pure joy: a moment that evokes so perfectly the energy that African-America has contributed to the country's culture.

This is a book that is almost impossible to pin down – like its author, who has always escaped categorisation and constantly re-invented himself. He segues both seamlessly and with dramatic contrast from crooner ballads to black protest, from love songs to existential angst. The book weaves together images of the road, the romance of departures and the pain of moving on, dreams of love and money. On one level, this is a portrait of the USA, stretched as the country is between myths of liberty and violence, spiritual transcendence and greed. Dylan has always understood this, in a visceral way that goes beyond what any other artist of his time has achieved.

There is, however, a truly shocking omission at the heart of the book: only a handful of the 66 songs are sung or written by women. How can this be? Could there more than a trace element of misogyny in the work of this apostle of radical change? This book doesn't claim to be comprehensive, and Dylan’s choices often delight with their apparent quirkiness. But it’s as if half of modern popular song had been censored or forgotten. Women are, of course, the subject of many of the songs Dylan has selected, but mostly as objects of love and desire. Women are present as well, as they voice Dylan's writing in the audiobook – and from Rita Moreno to Sissy Spacek, all of them very good.

The range of male archetypes summoned by the author suggests a lifelong fascination with the outlaw – a crucial figure in the American psyche, but within this recurring persona, there are variations, from violent gangsters to idealistic seekers of freedom. But for the women, the range is much narrower. The choice of songs like Santana’s “Black Magic Woman” and the Eagles' “Witchy” suggest that the femme is essentially fatale in Dylan’s universe. He may well sing of containing multitudes, but our Nobel Prize-winning idol is all too human, a man with flaws and limitations that reflect probably fundamental aspects of the still male-centred guiding myths of the USA.

- The Philosophy of Modern Song by Bob Dylan (Simon and Schuster 2022, £35.00)

- The Philosopy of Modern Song is available on Audible

- The songs included on The Philosophy of Modern Song can be heard on Spotify

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment