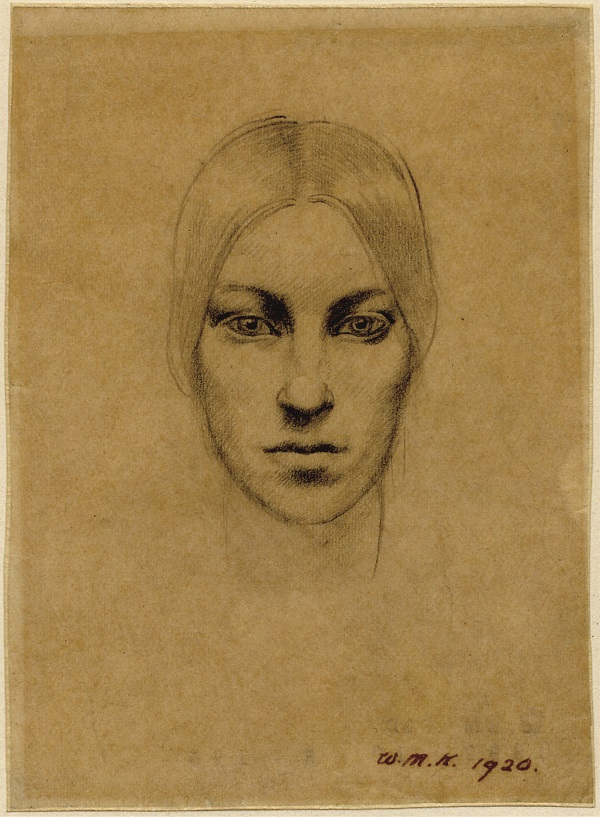

Winifred Knights (1899-1947) was an impeccable draughtsman: her portrait drawings are compelling. She deployed fine webs of lines, her sure hand applying gradated pressure resulting in mesmerising studies of people that are hypnotically fascinating. Who knew pencil could do so much? But she was also a painter, a slow worker using techniques that were deliberately old-fashioned.

As much of her surviving work as it is possible to retrieve is on view at Dulwich in an act of inspired re-discovery. The exhibition also tells us much about women artists near the beginning of the 20th century and of the emphases on skill, technique and the ability to make public paintings – notably murals – that were integral components of the curricula a century ago. Scrutinising her rare art is an example too of how we must continually refresh the story of art as we look at those major and minor artists – a Dulwich speciality – who have slipped from the collective memory (pictured below right: Self-portrait, 1920).

Winifred Knights had vanished almost completely. Her output was small for several reasons: she was of a nervous disposition, she had a passion for intense relationships, and she was a very slow and deliberate artist. She had a breakdown in the First World War partly as a consequence of the zeppelin raids over London, and she stopped working almost entirely in the latter part of her short life. Her subjects, allegorical in idioms that recalled perhaps most strikingly the still and captivating poses of early Renaissance painting, were by the 1930s in Britain – in spite of a neo-classical revival – almost completely unfashionable.

Winifred Knights had vanished almost completely. Her output was small for several reasons: she was of a nervous disposition, she had a passion for intense relationships, and she was a very slow and deliberate artist. She had a breakdown in the First World War partly as a consequence of the zeppelin raids over London, and she stopped working almost entirely in the latter part of her short life. Her subjects, allegorical in idioms that recalled perhaps most strikingly the still and captivating poses of early Renaissance painting, were by the 1930s in Britain – in spite of a neo-classical revival – almost completely unfashionable.

Her rediscovery casts light on art education at the volatile and highly influential Slade School in the early part of the last century (think Professor Henry Tonks, a superb portraitist who was crucial in helping surgeons with pioneering plastic surgery after the war, and Dora Carrington, Mark Gertler, Stanley Spencer amongst others). She was precocious; born in south London, she started at the Slade aged 16. She was gifted at illustration, slowly moving into work that was less specific and more meditative. She painted scenes of English life – an allotment, a Bank Holiday in a village, a market square with a sheep auction – giving them a curiously seductive, ritualistic flavour. Leaving the Munition Works, 1919, is replete with a variety of social interactions that serve as subtle notations of class. The main reason, of course, to look again is the skill and quality of her work.

Knights was the first woman ever to win the fiercely competitive Rome Scholarship in Decorative Painting, subsequently spending three years at the British School in Rome. In the 19th century almost every respectable and significant town hall, let alone major libraries, schools and religious buildings, commissioned murals, so it was not bizarre for artists to immerse themselves in the necessary techniques. The decorative mural, a wall painting that could be both decorative but also communicate a subject with a witty even profound visual intelligence, continued to be of import for the practice of art into the 20th century. The Deluge, 1920 (main picture), uses a palette more restricted than her later work inspired by Italy. It shows a barefoot group cascading upwards towards a hill that might help preserve them from the forthcoming cataclysm. The poses recall the new ways of using the body that were being exploited in modern dance.

Her five years in Italy, when she naturally and at the time unfashionably fell under the spell of Piero della Francesca, were formative. It allowed her in her finest work to show a contained choreographed energy in the stillest of poses, a frieze of people caught in frozen moments, and projecting a fierce yet subtle intensity. Her people, looking like statues, holding a pose so hard they might be quivering if we could but see, have feelings that are suppressed, repressed and about to explode. Her captivating painting of haunted stillness, The Marriage at Cana, 1923 (pictured left), has journeyed from New Zealand’s National Museum in Wellington, gifted there by the British School in 1957.

Her five years in Italy, when she naturally and at the time unfashionably fell under the spell of Piero della Francesca, were formative. It allowed her in her finest work to show a contained choreographed energy in the stillest of poses, a frieze of people caught in frozen moments, and projecting a fierce yet subtle intensity. Her people, looking like statues, holding a pose so hard they might be quivering if we could but see, have feelings that are suppressed, repressed and about to explode. Her captivating painting of haunted stillness, The Marriage at Cana, 1923 (pictured left), has journeyed from New Zealand’s National Museum in Wellington, gifted there by the British School in 1957.

Edge of Abruzzi, 1924-1930, is a calm Italian landscape, yellow sun-dried hills lie row upon row into the distance, underneath a quietly radiant, pale blue Italian sky while in the foreground a still lake bears a boat with a human trio. The Santissima Trinita, 1924-1930, shows curled-up figures again in a powerfully bleached Italian landscape. In an extraordinarily modern and fascinating variation on all she had absorbed from Italian Renaissance art is an ambitious Scenes from the Life of Saint Martin of Tours, 1928-1933, done for Canterbury Cathedral, bathed in an intense clarity.

This is an exhibition that slowly yields its pleasures, and in the frenetic time we currently inhabit, it is also curiously soothing. In a not uncommon paradox, her troubled life did not impair the serenity of her art.

- Winifred Knights (1899-1957) at Dulwich Picture Gallery until 18 September

- Read more visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment