Thirteen years ago, I visited the magnificent Morgan Library & Museum with the actress Charlotte Gainsbourg, whom I was profiling for The New York Times. She was starring in Franco Zeffirelli’s Jane Eyre, and it made sense for us to view the Morgan’s exhibition of Brontë juvenilia together. Gainsbourg seemed haunted by the show; I know I was. It was the sight of the tiny writing, the tiny gloves (Charlotte Brontë’s), and the locks of thin blondish Brontë hair - close enough to touch - under the glass cabinets. One could feel the siblings’ unquiet slumbers.

There’s none of William Blake’s hair in the Morgan’s current Blake exhibition - another oasis of fiery English passion in midtown Manhattan. Instead, there are more than 100 engravings, paintings, books, and letters, including a wall dedicated to works by Blake’s acquaintances, including Henry Fuseli and Samuel Palmer, and his followers. Culled from the museum’s own holdings, the exhibition contains Blake’s catalogue for the show of 16 works he held in London 200 years ago. It doesn’t celebrate that ill-fated event specifically, perhaps because the Morgan didn’t want to seem to follow the Tate Britain’s recent bicentennial tribute to Blake’s show.

The largest exhibits are Blake’s 21 watercolours for The Book of Job (1805-10), his 12 watercolour drawings for John Milton’s twinned poems L’Allegro and Il Penseroso (1816-20), and his gorgeously coloured relief etchings for his mythopeic poems in the illuminated books America a Prophecy (1793), Europe a Prophecy (1794), and The Song of Los (1795). Looking at these works and the others on display, the visitor is struck by the emotional extremes in Blake’s works. Everywhere there is night and day, heaven and hell.

The largest exhibits are Blake’s 21 watercolours for The Book of Job (1805-10), his 12 watercolour drawings for John Milton’s twinned poems L’Allegro and Il Penseroso (1816-20), and his gorgeously coloured relief etchings for his mythopeic poems in the illuminated books America a Prophecy (1793), Europe a Prophecy (1794), and The Song of Los (1795). Looking at these works and the others on display, the visitor is struck by the emotional extremes in Blake’s works. Everywhere there is night and day, heaven and hell.

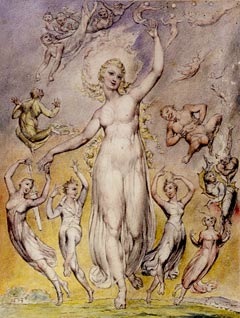

The illustrations to the Milton poems echo The Songs of Innocence and of Experience (1789-94) in their contrasting of different states of being. In Mirth, the first L’Allegro drawing, a yellow-haired nymph, dressed in a diaphanous gown, her head cocked provocatively to one side, gambols in the sunlight with other nymphs as more of them swoop from the sky and a small elf-like creature holds his sides with laughter. The image is a celebration of merriment and liberty, but it’s persuasively sexy, too. It contrasts with Melancholy in the Il Pensosero drawings. This shows a woman dressed in gray raiment—“pensive Nun Devout and pure”—who has turned her eyes heavenwards; other contemplative figures linger at her feet while one woman lies torpid in the air and the moon goddess Cynthia is borne away by dragons. In Milton’s poem, melancholy equates to meditativeness, not depression, but there is a mournfulness about the expression of the woman in the drawing.

Also worth comparing are The Sun at the Eastern Gate, from L’Allegro, and The Sun in His Wrath, from Il Pensosero. The former depicts a magnificent spiky-haired Apollo emerging with a phallic wand from a circle of fire as nymphs trumpet daybreak—according to Blake, this sun god symbolizes Milton’s spiritual and creative regeneration. In the latter, the same sun god, flinging black darts, descends on his fiery orb toward Milton being led by Melancholy into the shadowy groves of twilight as winged insects fostered by the sun hover over the spirits of the trees. This is not a negative space, but a place where, in Milton’s words, "I may sit and rightly spell… Till old experience do attain/ To something like prophetic strain.” The drawing makes one wonder if Blake sat up writing through the night in his back parlour at Lambeth until the town crier came around.

The melancholy mood is sustained by one of the most lyrical exhibits in the exhibition, the atlas-sized book of Edward Young’s nine-part poem Complaint and the Consolation, or Night Thoughts on Life, Death, & Immortality (1742-45). Collaborating on the monumental project with an undistinguished London publisher, Blake made 537 watercolour illustrations for it—five a week for over two years—and planned to engrave about 200 of them for the text pages. The first volume, which was published in 1797, had 43 engravings. That this was a labour of love is indicated by the practice, also used in Blake’s watercolour illustrations for Thomas Gray’s Poems (1790), of mounting the text leaves over the engravings on the larger leaves, thus partially obscuring them. Young was a member of the Graveyard school of English poets, whose gloomy meditations on mortality predated Romanticism: Night Thoughts contains the line, “Procrastination is the thief of time.”

The melancholy mood is sustained by one of the most lyrical exhibits in the exhibition, the atlas-sized book of Edward Young’s nine-part poem Complaint and the Consolation, or Night Thoughts on Life, Death, & Immortality (1742-45). Collaborating on the monumental project with an undistinguished London publisher, Blake made 537 watercolour illustrations for it—five a week for over two years—and planned to engrave about 200 of them for the text pages. The first volume, which was published in 1797, had 43 engravings. That this was a labour of love is indicated by the practice, also used in Blake’s watercolour illustrations for Thomas Gray’s Poems (1790), of mounting the text leaves over the engravings on the larger leaves, thus partially obscuring them. Young was a member of the Graveyard school of English poets, whose gloomy meditations on mortality predated Romanticism: Night Thoughts contains the line, “Procrastination is the thief of time.”

Blake was reading the poem, he told his portraitist Thomas Phillips, when he was visited by the Archangel Gabriel, “a shining shape with bright wings", who told him in answer to Blake’s musing question, “Who can paint an angel?”, that Michelangelo assuredly could. In the exhibition, the book is open to a spread showing the final page of Night the First and the title page of Night the Second on Time, Death and Friendship. In the picture on the left, the soul, personified by a harpist, who is chained to the brambly earth, arches in the air as he or she futilely reaches for the heavens, struggling for immortality, the absence of which is lamented by Young as he conjures the music of the nightingale and the great bards. On the right we see a contest between two of Blake’s hoary old men: Time sits back on the earth as he despairingly tries to stop Death from firing an arrow at the smaller figures of two friends. The watercolouring, possibly by Catherine Blake, the engraver’s wife, delicately enhances the flowing lines of the images.

The publisher, who paid Blake the paltry sum of 20 guineas for his work on Night Thoughts, didn’t promote the book and there were no further volumes. The failure badly hurt Blake, who had neglected his engraving business to work on the project. At a Royal Academy committee meeting at Wright’s Coffee House in 1797, one of the members likened Blake’s effort to “a man sitting on the moon, and pissing the Sun out - that would be a whim of as much merit". William Hazlitt, commenting on the plates in 1811, “saw no merit in them as designs". G E Bentley Jr, whose excellent Blake biography The Stranger from Paradise tracks the creation of Night Thoughts, remarks, “As on many other occasions, Blake’s attempt to represent spiritual forces in heroic dimensions was taken to be eccentric and absurd, an extravagance bordering on madness.” Walk quickly through the lobby outside the Blake exhibit and you can miss the case containing Night Thoughts, his most ambitious undertaking.

Around the corner is the small engraving Joseph of Arimathea Among the Rocks of Albion, which Blake made as a 16-year-old apprentice in 1773 and reworked in 1810. The print, after Michelangelo, shows Christ’s gravedigger, who brought the Grail to England, as a bulky greybeard standing on a rocky shore. Joseph is powerful but clearly suffering. Blake’s subtitle reads: “This is one of the Gothic artists who Built the Cathedrals in what we call the Dark Ages Wandering about in sheep skins & goat skins of whom the World was not worthy such were the Christians in all ages.” The image celebrates the isolation of the artist, a status that Blake would come to share.

On the same wall sits Blake’s hand-coloured engraving of Chaucer and his 29 Canterbury pilgrims (original tempera painting c.1808) embarking from the Tabarde Inn in Southwark. Blake had supposedly given the idea for A Canterbury Tales single-plate print to his publisher Robert Cromek, who commissioned the more commercially successful Thomas Stothard to design it instead. That version was exhibited in 1806 and sold well. Enraged by this betrayal, Blake held his 1809-10 exhibition in his brother’s Soho shop to showcase his Canterbury Tales painting; for the catalogue, he wrote pages of literary criticism about the pilgrims, whose habits, dress, even their horses, he’d researched assiduously.

Blake’s largest engraving is thick with humanity, the faces of the pilgrims expressing an array of emotions as they anticipate their journey. Look carefully and you can see gravity, doubt, sternness, worry, and class-consciousness. The Knight and the Squire have pulled away from the rest. The Friar and the Monk seem to be confiding about their fellow travellers, commenting, perhaps, on the beauty of the Nun. Arms spread, the plump Host, at the centre, wants to dominate the whole show. Chaucer is preoccupied, the Oxford scholar uncertain. The smiling Wife of Bath, who wears a fantastic headdress, has sluttishly exposed her nipples, and, like the Cook, is already drinking. The Reeve, bringing up the rear, looks even-tempered enough in this version of the engraving; in the one in Pollok House, Glasgow, he is downright surly. It is a great piece of popular art. According to Bentley, Blake made a profit on the print sales without matching Stothard’s figures.

Above all, The Canterbury Tales engraving is a happy work, full of expectation. At the Morgan, it sits next to one of the most disturbing works in the show, the unpublished engraving Satan (c.1790), which originated with Fuseli. It depicts the head of a bull-necked man seen howling in anguish from a low angle. He’s not Satan but a man in Satan’s grip, which aligns him with Job on the opposite wall. Blake traces Job’s ordeal from its beginning to his final redemption, but the eyes are drawn to the scenes of greatest suffering, apocalyptic in their imagery: the winged Satan, perched on collapsing columns, prevails over the destruction of Job’s sons and daughters as they desperately try to rescue themselves; Satan stands on Job’s body as he hoses a torrent of boils onto him; Satan, wrapped in a serpent, hovers over Job’s tormented sleep, this design echoing Elohim Creating Adam and other Blake designs in which two figures are arranged horizontally, the top one menacing the other. Blake suggests Job is being punished for observing the letter of conventional religion rather than the spirit, but he also makes The Book of Job an existential parable about a hapless victim in the war between God and Satan.

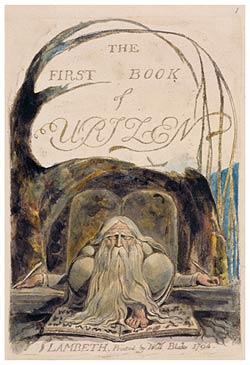

There are iconic Blakean images in the show including two relief etchings of The Tyger (1795) - the meek, fangless tiger sitting incongruously beneath Blake’s poem about the dreadful force of creation - from The Songs of Experience. One was printed in brown by Blake, the other was hand-coloured after Blake’s death in 1827. Along with three other images displayed from Europe a Prophecy, the famous frontispiece The Ancient of Days (1794) shows the figure of Urizen (pictured right), Blake’s concept of the false Old Testament God - spirit of tyranny, queller of energy and represser of the imagination. White-bearded and windswept, he crouches in a cramped red sphere as he circumscribes the universe with a pair of golden dividers. This God is a human construct; Blake makes him frighteningly omnipotent. He coloured a copy of the print on his deathbed. The leaf on the wall at the Morgan is small but magnetic.

There are iconic Blakean images in the show including two relief etchings of The Tyger (1795) - the meek, fangless tiger sitting incongruously beneath Blake’s poem about the dreadful force of creation - from The Songs of Experience. One was printed in brown by Blake, the other was hand-coloured after Blake’s death in 1827. Along with three other images displayed from Europe a Prophecy, the famous frontispiece The Ancient of Days (1794) shows the figure of Urizen (pictured right), Blake’s concept of the false Old Testament God - spirit of tyranny, queller of energy and represser of the imagination. White-bearded and windswept, he crouches in a cramped red sphere as he circumscribes the universe with a pair of golden dividers. This God is a human construct; Blake makes him frighteningly omnipotent. He coloured a copy of the print on his deathbed. The leaf on the wall at the Morgan is small but magnetic.

Europe a Prophecy ends apocalyptically with France engulfed by a bloody revolution. After looking at Urizen, I turned to the watercolour print Fire, which shows people in the midst of an apocalyptic firestorm. Blake painted it as a part of a series with Pestilence, Famine, and War in 1805.

It was evocatively described by Alexander Gilchrist, whose 1863 biography of Blake rescued his reputation and consecrated him as a great artist and writer: “The watercolour is unusually complete in execution. The conflagration, horrid in glare, horrid in gloom, fills the background; its javelin-like cones surge up amid conical forms of buildings… In front, an old man receives from two youths a box and a bundle which they have recovered; two mothers and several children crouch and shudder, overwhelmed; other figures behind are running about, bewildered what to do next.” The box resembles a child’s coffin. Blake was probably thinking of the French Revolution, but the painting and the terrible images of burning in his poems were influenced by his memories of the Gordon Riots in 1780. Fire made me think of Dresden and 9/11.

I’ve tried to imagine Blake toiling with his copperplates and his engraving tools or his rolling press. I’ve tried to imagine him painting the red-tipped flames on The Sun at His Eastern Gate, or sitting in a trance while writing The Tyger. I’ve tried to imagine him receiving his visions of Edward I, Satan, a fairy, and the ghost of a flea. But Blake so floods us with his industry and the aura of the seer that the man is hard to grasp. The Morgan’s exhibition brings him as close as it’s possible to get, hair or no hair.

William Blake's World: "A New Heaven Is Begun" runs at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York until 3 January 2010. The exhibition can be viewed here.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment