An Open Book: David Lan | reviews, news & interviews

An Open Book: David Lan

An Open Book: David Lan

The Young Vic's artistic director on Steinbeck, his love of social history, and the only theatre book 'that really matters'

This year’s Olivier Awards saw the Young Vic trounce its South Bank neighbours, with Ivo van Hove’s revolutionary A View from the Bridge leading 11 nominations and four wins; the production opens on Broadway next week. It reflects an extraordinary period during which the theatre, originally an offshoot of the National, has grown to become one of Britain’s major creative powerhouses – all under the aegis of South African-born David Lan, artistic director since 2000.

Following a £12.5 million revamp, the Young Vic now attracts daring experimental artists from Europe and beyond, both big names and rising stars – with a particular emphasis on nurturing young directors. This wide-ranging international conversation has been skillfully cultivated by Lan, 63, whose own career includes stints as an actor, playwright, director, documentary-maker, translator, opera librettist and social anthropologist; he did two years’ field research as the latter in the Zambezi Valley. Lan also co-founded the What Next? movement, responding to an increasingly urgent need for championing the arts in a tough political climate, and was awarded a CBE for services to theatre in 2014.

What books are you currently reading?

The Death of Woman Wang by Jonathan Spence. I’ve been reading a lot of early modern European history. For example, Brendan Simms’ amazing Europe: The Struggle for Supremacy, which anyone who thinks we ought to get “out of” Europe needs to read – Simms reveals how deeply and inextricably enmeshed in Europe we’ve been since 1453. I’m especially interested in the period 1789 to 1914, which (obviously) should be on the curriculum of every child to make indelible in their minds the foolishness and arrogance of their political leaders and the need to challenge them at every step. Jonathan Spence’s micro-histories of Chinese life at roughly the same period suggest (just like Simms) that deep social change takes a long time, if it ever really happens at all.

I sat in a seaside café on the island of Giglio and wept at the death of Isabel Archer

Who is your favourite novelist?

I often go back to Joseph Conrad and DH Lawrence, who were more or less contemporaries. In their different ways, their books are so packed full of ambivalence that, at whatever age you read them, they feel like major discoveries. I don’t like The Secret Agent (the plot is so overdetermined it feels smug), but I love Nostromo and Under Western Eyes and especially Lord Jim. And Sons and Lovers you can read time after time. I love the first 200 pages of anything by Zola, but then he goes dead on you. I reread The Quiet American by Graham Greene over the summer and now think it’s his best book (I used to think it was The Heart of the Matter, which is also great and theologically heart-stopping).

Do you have a favourite non-fiction writer?

Amongst historians, Richard J Evans and Ian Kershaw are finer stylists than most English novelists. Mark Mazower’s Salonica, City of Ghosts and Norman Davies’ Rising ’44 are both in the "Best book ever" category. Robert Caro’s multi-volume biography of Lydon B. Johnson is genius social history. I’ve read volumes three and four; life may be too short for the rest. I’m just getting going on Jonathan Sumption’s four volumes (so far) on the Hundred Years War. He can write all right.

Do you read poetry? If so, is there a poet or a poem you always return to?

I don’t warm to TS Eliot, but I have a number of his big ones by heart – I don’t know why. There is some of Yeats I need never read again – they’re in the blood. I love Thom Gunn.

Tell us about your favourite books on drama.

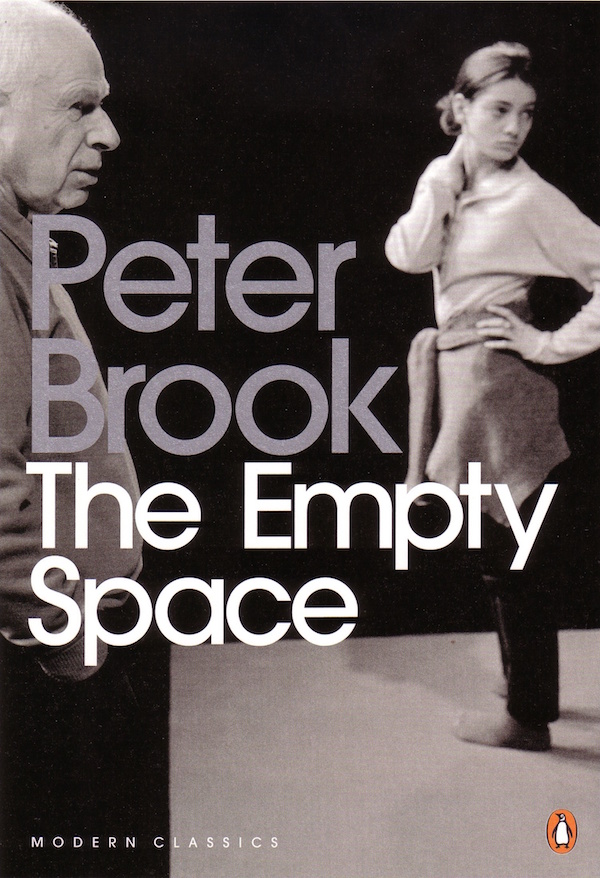

My Life in Art by Konstantin Stanislavsky has the great story of him and Nemirovich-Danchenko working out that they need x million roubles to start the Moscow Art Theatre, worrying terribly about where they could possibly find them, then going out for dinner and spending half the amount they need in a single evening. The Empty Space by Peter Brook (pictured right) is the only book on theatre that really matters. The opening sentence is almost as famous as that of the Bible. Dance to the Piper by Agnes de Mille has the best last page, saying (I paraphrase) “Stop worrying about whether you’re any good or not – that’s nothing to do with you. You have it in you to create something that no one else on the planet ever will. If you don’t do it, it will never happen, so just shut up and get on with it.” My credo.

My Life in Art by Konstantin Stanislavsky has the great story of him and Nemirovich-Danchenko working out that they need x million roubles to start the Moscow Art Theatre, worrying terribly about where they could possibly find them, then going out for dinner and spending half the amount they need in a single evening. The Empty Space by Peter Brook (pictured right) is the only book on theatre that really matters. The opening sentence is almost as famous as that of the Bible. Dance to the Piper by Agnes de Mille has the best last page, saying (I paraphrase) “Stop worrying about whether you’re any good or not – that’s nothing to do with you. You have it in you to create something that no one else on the planet ever will. If you don’t do it, it will never happen, so just shut up and get on with it.” My credo.

Crime or sci-fi?

Crime: I’ve read almost every Michael Connelly, much of Elmore Leonard, all of Raymond Chandler. Most crime writing is too slapdash or violent to bother with.

Any genres you can’t get on with?

Sci-fi except HG Wells – his first four books are all amazing masterpieces. The ones he wrote after are unreadable.

Which books have made you really, properly cry?

I sat at a table in a seaside café on the island of Giglio and wept at the death of Isabel Archer in The Portrait of a Lady by Henry James.

If you could choose to be any fictional hero or heroine who would it be?

David Balfour in Kidnapped by Robert Louis Stevenson. His long walk fleeing across Scotland is unforgettable – I think I’ve been there. I always get lost in the politics (an "auld alliance" between Scotland and France, who knew?), but it’s a fabulous moral adventure story – like life.

Which fictional character can you imagine falling in love with?

Misail Poloznev in My Life by Anton Chekhov. If you want to know why, read this 100-page story. It’s as great as any of his plays.

Which four writers would you invite to your ideal dinner party?

Doris Lessing, Vasily Grossman (author of Life and Fate), Nina Simone, Paul Mason.

Which book made you think: “I must get this for all my friends”?

The Number by Jonny Steinberg is 300 pages of life inside a prison in South Africa. It’s also about life inside the heads of the prisoners. It’s an extraordinarily detailed ethnography of an entire society within a society, of the mythology and ritual and etiquette – sexual and moral – of gang culture. You think: he must have made it all up, you can’t believe his research was that good – but you believe every word. It’s thrilling and appalling and almost entirely unknown in this country – which is a crime in its own right.

Has a book ever changed your life?

I read The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck when I was about 14. I’ve reread it at least once a decade. For me, it’s the "Book": it’s what a book is, what every other book has to measure up to.

Why do you read?

I read a good deal for the work I do, a fair number of plays, new ones of course but also older ones to see if their bloodstream has bubbled up again or if it’s dried out on the shelf. I read books and articles that relate to or inform (I hope) the shows we produce. But I also read to get away from all that – unremittingly, compulsively, as though there are a certain number of books I have to get through and then that will be reading finally done. But every week a few more turn up on the doorstep.

- Measure for Measure at the Young Vic until 14 November, and Belarus Free Theatre’s Staging a Revolution festival runs 2-14 November at the Young Vic and various secret locations

Explore topics

Share this article

more Theatre

London Tide, National Theatre review - haunting moody river blues

New play-with-songs version of Dickens’s 'Our Mutual Friend' is a panoramic Victori-noir

London Tide, National Theatre review - haunting moody river blues

New play-with-songs version of Dickens’s 'Our Mutual Friend' is a panoramic Victori-noir

Machinal, The Old Vic review - note-perfect pity and terror

Sophie Treadwell's 1928 hard hitter gets full musical and choreographic treatment

Machinal, The Old Vic review - note-perfect pity and terror

Sophie Treadwell's 1928 hard hitter gets full musical and choreographic treatment

An Actor Convalescing in Devon, Hampstead Theatre review - old school actor tells old school stories

Fact emerges skilfully repackaged as fiction in an affecting solo show by Richard Nelson

An Actor Convalescing in Devon, Hampstead Theatre review - old school actor tells old school stories

Fact emerges skilfully repackaged as fiction in an affecting solo show by Richard Nelson

The Comeuppance, Almeida Theatre review - remembering high-school high jinks

Latest from American penman Branden Jacobs-Jenkins is less than the sum of its parts

The Comeuppance, Almeida Theatre review - remembering high-school high jinks

Latest from American penman Branden Jacobs-Jenkins is less than the sum of its parts

Richard, My Richard, Theatre Royal Bury St Edmund's review - too much history, not enough drama

Philippa Gregory’s first play tries to exonerate Richard III, with mixed results

Richard, My Richard, Theatre Royal Bury St Edmund's review - too much history, not enough drama

Philippa Gregory’s first play tries to exonerate Richard III, with mixed results

Player Kings, Noel Coward Theatre review - inventive showcase for a peerless theatrical knight

Ian McKellen's Falstaff thrives in Robert Icke's entertaining remix of the Henry IV plays

Player Kings, Noel Coward Theatre review - inventive showcase for a peerless theatrical knight

Ian McKellen's Falstaff thrives in Robert Icke's entertaining remix of the Henry IV plays

Cassie and the Lights, Southwark Playhouse review - powerful, affecting, beautifully acted tale of three sisters in care

Heart-rending chronicle of difficult, damaged lives that refuses to provide glib answers

Cassie and the Lights, Southwark Playhouse review - powerful, affecting, beautifully acted tale of three sisters in care

Heart-rending chronicle of difficult, damaged lives that refuses to provide glib answers

Gunter, Royal Court review - jolly tale of witchcraft and misogyny

A five-women team spell out a feminist message with humour and strong singing

Gunter, Royal Court review - jolly tale of witchcraft and misogyny

A five-women team spell out a feminist message with humour and strong singing

First Person: actor Paul Jesson on survival, strength, and the healing potential of art

Olivier Award-winner explains how Richard Nelson came to write a solo play for him

First Person: actor Paul Jesson on survival, strength, and the healing potential of art

Olivier Award-winner explains how Richard Nelson came to write a solo play for him

Underdog: the Other, Other Brontë, National Theatre review - enjoyably comic if caricatured sibling rivalry

Gemma Whelan discovers a mean streak under Charlotte's respectable bonnet

Underdog: the Other, Other Brontë, National Theatre review - enjoyably comic if caricatured sibling rivalry

Gemma Whelan discovers a mean streak under Charlotte's respectable bonnet

Long Day's Journey Into Night, Wyndham's Theatre review - O'Neill masterwork is once again driven by its Mary

Patricia Clarkson powers the latest iteration of this great, grievous American drama

Long Day's Journey Into Night, Wyndham's Theatre review - O'Neill masterwork is once again driven by its Mary

Patricia Clarkson powers the latest iteration of this great, grievous American drama

Opening Night, Gielgud Theatre review - brave, yes, but also misguided and bizarre

Sheridan Smith gives it her all against near-impossible odds

Opening Night, Gielgud Theatre review - brave, yes, but also misguided and bizarre

Sheridan Smith gives it her all against near-impossible odds

Add comment