On the 35th anniversary of the year punk met the mainstream, it’s to be expected that retrospection and nostalgia are in the air. Television has had a go, albums are being reissued and old soldiers are telling their stories. By its very nature an anniversary suggests that things were cut and dried, that 1977 was a beginning or a marker in the sand. But the exhibition Someday All the Adults Will Die: Punk Graphics 1971-1984 at the Southbank’s Hayward Gallery Project Space and the publication of the related book Punk: An Aesthetic both underline that things aren’t and weren’t so clear.

Both the exhibition and book are the brainchild of writer Jon Savage, the author of England’s Dreaming, still the best biography of the punk era, and writer/collector/archivist Johan Kugelberg, who has previously curated exhibitions dedicated to the May ’68 Paris uprisings and the art of The Velvet Underground.

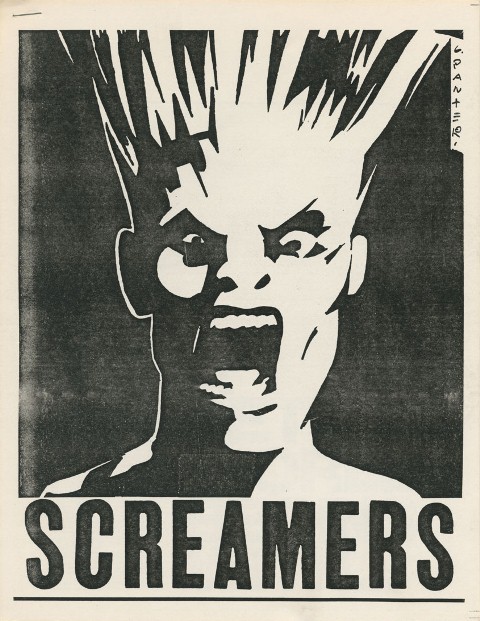

“Neither Johan or I buy the year zero line anymore,” says Savage. “Obviously it was important at the time. It was right then that punk had no antecedents. The story of punk is a lot more complex than people think A lot of the historical discussion is very trite.” (Pictured right, Gary Panter’s poster for LA band The Screamers, 1977)

“Neither Johan or I buy the year zero line anymore,” says Savage. “Obviously it was important at the time. It was right then that punk had no antecedents. The story of punk is a lot more complex than people think A lot of the historical discussion is very trite.” (Pictured right, Gary Panter’s poster for LA band The Screamers, 1977)

For Kugelberg, punk “is the last macro tribe. If there is a legacy of the aesthetic of punk, it’s the diminution of the distance between the self-starter impulse and its execution. The self-starter impulse reached around the globe.”

Looking at the artefacts and art gathered for both the book and exhibition, it’s clear the era’s urgent atmosphere led to a slap-dash, speedy execution which suggests a lot of them would have been disposable. The last thing that would be expected is for them to have ended up under glass on display, whether it’s a one-off fanzine, a DIY single or a punk cash-in issue of teen mag Oh Boy.

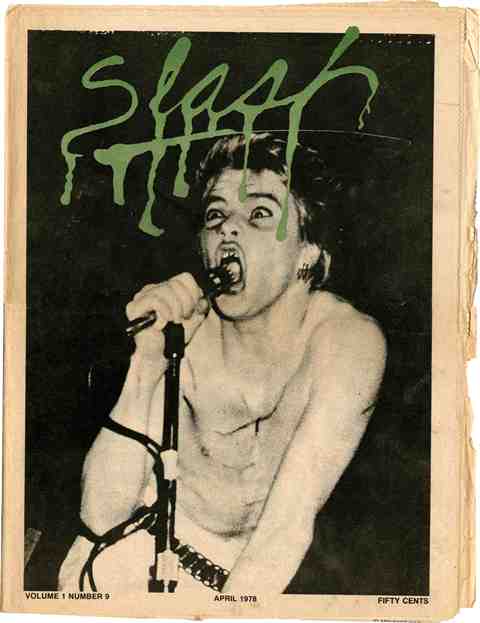

“Punk has been assimilated into culture,” contends Savage. “I see no contradiction [in the material being in a gallery]. It’s just good for people to see this. I like it; all I want is for people to have fuel. You want to find out what the good stuff is, the weird stuff. So I think it is important for this to be seen”. (pictured left, Darby Crash of LA band The Germs on the cover of Slash magazine, 1978)

“Punk has been assimilated into culture,” contends Savage. “I see no contradiction [in the material being in a gallery]. It’s just good for people to see this. I like it; all I want is for people to have fuel. You want to find out what the good stuff is, the weird stuff. So I think it is important for this to be seen”. (pictured left, Darby Crash of LA band The Germs on the cover of Slash magazine, 1978)

Kugelberg stresses that “the historical and ephemeral does need to be preserved, but there’s too much of a grassroot in all of us with this to say that this is nostalgia. Punk is going to inspire people 200 years after we’re dead. This is the opposite of nostalgia, it inspires me to want to do more stuff. Look right now at Pussy Riot”.

That said, Someday All the Adults Will Die and Punk: An Aesthetic are both goldmines of astonishing imagery and artefacts, and can be seen as a parade of collectables to slather over. The exhibition showcases the original artwork for New York’s Punk magazine and also includes a real copy of the withdrawn Sex Pistol's A&M “God Save The Queen” single. It’s a rare opportunity to see a fabulous, mind-blowing set of early Sex Pistols’ concert flyers.

But beyond the individually eye-catching, there are some items – and groups of items – which even at this late stage reconfigure how punk is seen. Hidden on the wall leading into the exhibition’s main space is a handwritten set list from an early rehearsal by the proto-Sex Pistols, possibly from when they were still called The Strand. It’s in the hand of lost early member Warwick Nightingale. There are familiar song titles – such as “Did You No Wrong” – but the cover versions listed include The Count Five's garage-psyche nugget “Psychotic Reaction”, The Small Faces’ “Understanding" and The Stooges’ “Shake Appeal”. It’s all the proof needed that there could never have been a year zero, even for the future leaders of Brit punk.

Any remaining idea that punk sprang fully formed from nowhere is kicked aside by art and fanzines from people associated with punk. A 1971 copy of Jamie Reed's Suburban Press is displayed, along with a fanzine made by Patti Smith’s guitarist, Lenny Kaye. It’s from 1962. Both are homemade and wouldn’t have looked out of place in 1977. If there was a punk aesthetic, it was there long before spiky hair and spitting.

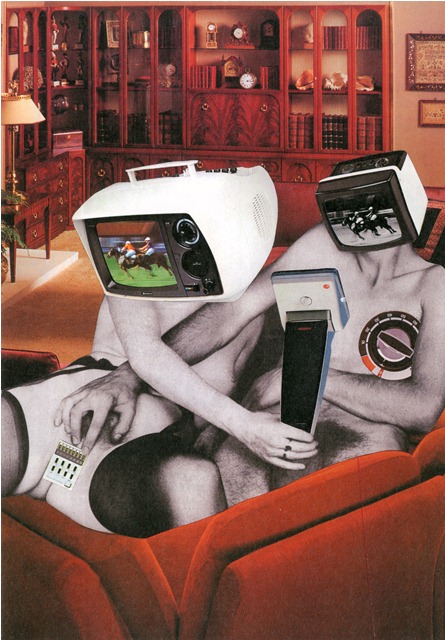

Although the images and art seen are often deliberately crude, bringing a directness, singular artistic voices emerge. Artist Gary Panter’s work for LA band The Screamers is timeless. With punk, Jamie Reid found a vehicle which took his subversive, reinterpretive style to a wide audience. Linder Sterling’s collages still shock. (Pictured right, Linder Sterling’s montage TV Sex for Secret Public, 1977)

Although the images and art seen are often deliberately crude, bringing a directness, singular artistic voices emerge. Artist Gary Panter’s work for LA band The Screamers is timeless. With punk, Jamie Reid found a vehicle which took his subversive, reinterpretive style to a wide audience. Linder Sterling’s collages still shock. (Pictured right, Linder Sterling’s montage TV Sex for Secret Public, 1977)

Asked which item or image in the exhibition speaks most of the possibilities of punk and has the greatest resonance, Kugelberg instantly zooms to the work of Gee Vaucher, whose art for anarcho-punks Crass was both considered and immediate, and has a rare depth making it work on multiple levels. “It’s hard to disentangle the impact of Gee and [Crass’s] Penny Rimbaud and Steve Ignerent, but Gee, to me, defines what this exhibition is about. It’s about graphic design.”

Neither the book or the exhibition make it easy to determine what the narrative – or narratives - might be. The captions in the exhibition space are minimal and the few expository panels can be gnomic. The book includes essays, but little contextualisation. Kugelberg says “the narrative is a real maze”.

Savage argues that “there is a difference between punk as an aesthetic and punk as an era and place. It’s still open to be commodified. There’s a shorthand for punk. But it’s still open to be debated.”

With Someday All the Adults Will Die: Punk Graphics 1971-1984 and Punk: An Aesthetic refusing to be confined by limits and definitions neither are an easy ride. Perhaps what's thought of as punk can now become even wider.

Add comment