While most will be familiar with him as an actor, and some will know him also as a photographer and painter, few will be aware of the full extent of the late Dennis Hopper’s artistic practice. Hopper, who died in May of this year, did everything from taking photographs of Dr Martin Luther King Jr during the historic Selma-Montgomery marches through producing oil paintings inspired by the scale of billboards to making pop-art assemblages, abstracts, and painting large-scale figures appropriated from commercial advertising.

But then Hopper was always a terribly tricky person to pin down. While most will be familiar with him as an actor, and some will know him also as a photographer and painter, few will be aware of the full extent of the late Dennis Hopper’s artistic practice. Hopper, who died in May of this year, did everything from taking photographs of Dr Martin Luther King Jr during the historic Selma-Montgomery marches through producing oil paintings inspired by the scale of billboards to making pop-art assemblages, abstracts, and painting large-scale figures appropriated from commercial advertising. But then Hopper was always a terribly tricky person to pin down.

'Mummy loves you': Dennis Hopper as Frank Booth in Blue Velvet

How does one reconcile the central-casting villain of Speed with the genuinely creepy, oxygen-huffing Frank Booth from Blue Velvet; the mind-addled photojournalist of Apocalypse Now with the wide-eyed youth from Rebel without a Cause; the crumbling alcoholic father in Rumblefish with the doomed hippie from Easy Rider? So it goes with his less well-known career.

The other side to Dennis Hopper makes Double Standard, a comprehensive retrospective of his work curated by Julian Schnabel, a shrewd choice for Jeffrey Deitch’s first show as incoming director of the Geffen Contemporary. But then there is another side to Deitch too.

First, the Geffen (pictured right). Set back from the street in the Little Tokyo neighbourhood, across from the warm brick of the Nishi Hongwanji Buddhist temple and abutting the cool elegance of the Japanese American National Museum, it is a large, open, rough-looking building which was once a warehouse used for police car storage. While the Museum of Contemporary Art Grand Avenue was being built, it was used as an exhibition space known as the Temporary Contemporary. Then it was renovated by Frank Gehry and is nowadays an official extension of MoCA. Something of the old informality remains, with a large, windowed wall filling the multileveled space with southern California light.

First, the Geffen (pictured right). Set back from the street in the Little Tokyo neighbourhood, across from the warm brick of the Nishi Hongwanji Buddhist temple and abutting the cool elegance of the Japanese American National Museum, it is a large, open, rough-looking building which was once a warehouse used for police car storage. While the Museum of Contemporary Art Grand Avenue was being built, it was used as an exhibition space known as the Temporary Contemporary. Then it was renovated by Frank Gehry and is nowadays an official extension of MoCA. Something of the old informality remains, with a large, windowed wall filling the multileveled space with southern California light.

Not an academic but a gallerist, Deitch enters the museum world with some controversy. Despite closing his gallery, Deitch Projects, before commencing his new role, concerns remain about his close ties to artists. Ethical tangles might arise if their work is handled by the museum, and perhaps equally if, as a matter of policy, it is not. He has declared his intention not to return to commercial art dealing, but will not divest himself of his personal collection.

His ties to artists are matched by his ties to people like Eli Broad, the powerful arts patron, who sits on MoCA’s advisory board. If a critic is looking for a reason to be suspicious, one can be found. Now that the Los Angeles County Museum of Art has opened its Broad Contemporary Art Museum (yes, the same Broad), MoCA is no longer the only game in town when it comes to contemporary art, and will need to keep its vision and collection fresh. While many welcome Deitch’s business savvy and fundraising ability, he is still a consummate New York art world insider, and as such needs to sell himself to Los Angeles. Hence Hopper.

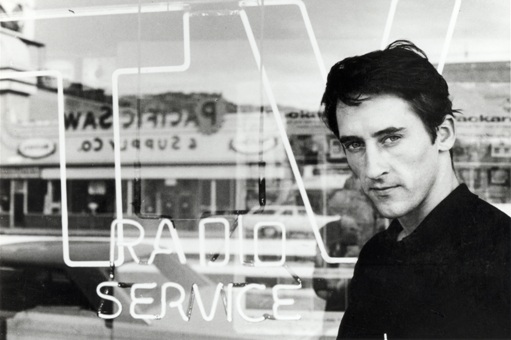

Much of Hopper's work was documentary. He photographed a substantial swathe of the contemporary arts scene, as seen exhibited here with his portraits of Edward Ruscha (pictured left: Edward Ruscha, 1964), Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol and James Rosenquist (main picture). Yet he was also a participant: together with Marcel Duchamp, he produced Hotel Green (Entrance), and he added a final fillip of two bullet holes to one of Warhol’s prints (of Mao Zedong) – not necessarily with the intention of producing an artistic collaboration. If some of his other forays are less successful, there is a sense that he tried everything at least once.

Much of Hopper's work was documentary. He photographed a substantial swathe of the contemporary arts scene, as seen exhibited here with his portraits of Edward Ruscha (pictured left: Edward Ruscha, 1964), Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol and James Rosenquist (main picture). Yet he was also a participant: together with Marcel Duchamp, he produced Hotel Green (Entrance), and he added a final fillip of two bullet holes to one of Warhol’s prints (of Mao Zedong) – not necessarily with the intention of producing an artistic collaboration. If some of his other forays are less successful, there is a sense that he tried everything at least once.

Schnabel, who knew Hopper, involved him in putting together the show, and it reflects how he understood himself as an artist working not only across media but also across styles. While the bulk of Hopper’s work at the time was lost in the 1961 fire that destroyed his Bel-Air home, the remainder is diverse. It reads as the output of an enthusiastic everyman - one who happened personally to know a huge number of contemporary American artists who were, or became, important.

Hopper’s deep love of photography is evident in the layout. The central room of the exhibit is filled with a large number of his black-and-white photographs, clearly his best work. Around the margins are pieces that are physically vast – La Salsa Man and Mobil Man, his painted fibreglass and steel figures, are over 20 feet tall, and the billboard-inspired paintings are about that wide.

Hopper’s films are relegated to a small screening room at the back end of the space. The clips chosen for the video include both performances, such as an unsettling scene in True Romance in which Hopper baits a racist mobster played by Christopher Walken, and a behind-the-scenes clip from the set of Apocalypse Now. It shows Francis Ford Coppola talking to Hopper about a previous take. The happy-go-lucky actor smiles and rambles, and in the end it’s difficult to determine whether his patter is delirious or inspired, or whether he’s just putting Coppola on. It's that same ambiguity which underpins the work on display in Double Standard.

Dennis Hopper and Christopher Walken in True Romance

Both images © The Estate of Dennis Hopper, courtesy of The Estate of Dennis Hopper and Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York

Add comment