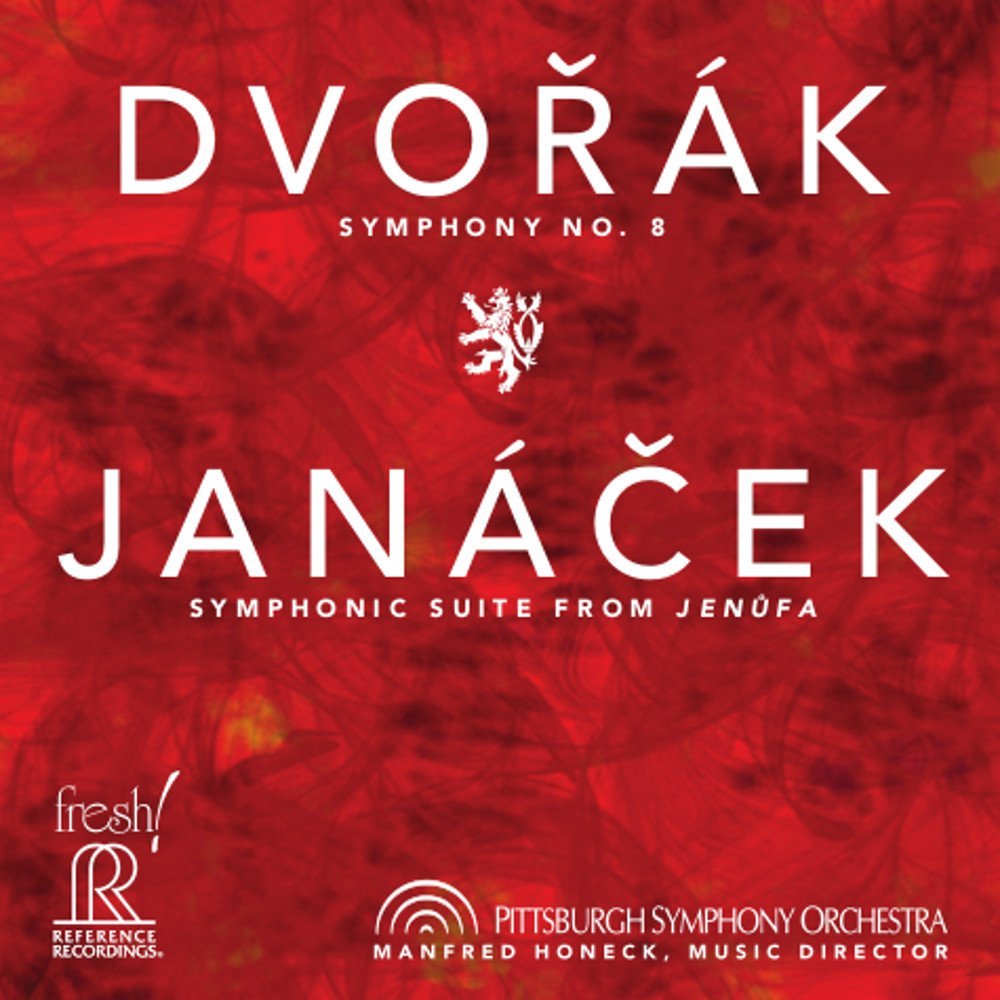

Dvořák's Seventh has the Brahmsian drama, and the Ninth has the crowd-pleasing tunes. But the major key Eighth is the most radical, and Manfred Honeck's remarkable performance highlights its originality in some style. Honeck's interventionist approach won't be to all tastes, but he justifies every interpretive decision in his sleeve notes, and the musical results are pretty special. He sees the composer here as ''liberated from Germanic models... completely at home in his native Czech roots”, stressing how close this work is to a programmatic symphonic poem. The solo flute's bird call is unusually flexible, improvisatory. What follows is electrifying – an exuberant adrenalin rush, and a wonderful easing into the rich lower string theme. There's real drama and darkness in the development, and the trumpet reprise of the symphony's opening chorale is magnificent. Listen out for the trilling horns near the close. The Adagio carries a seismic emotional punch – is this the greatest of Dvořák's slow movements? Lightness returns in the Allegretto. Sly string portamenti are audaciously done, and Honeck's treatment of the throwaway coda should elicit gurgles of delight. Trumpets are immaculate at the start of the finale, and Honeck's deliberate pacing of the variation theme allows him to let rip when the music accelerates, aided again by spectacular horns.The folky central section is superbly characterised. Reach the close, and you'll hopefully be awestruck. Cheap thrills and vulgarity are avoided. This is one of the great orchestral recordings – trust me. Playing and production values are beyond criticism.

And there's an intriguing coupling too – an orchestral suite from Janáček's opera Jenůfa, compiled by Honeck with the help of composer Tomáš Ille. Janaček's idiomatic use of folk music emphasises his debt to Dvořák, though the younger composer's startling orchestral technique remains unique. If you're not weeping at the suite's apotheosis, you've got no soul. Buy or download multiple copies for yourself and your loved ones – they will thank you for it.

Not all of Sir Colin Davis's last London Symphony Orchestra recordings were up to the mark – his Nielsen cycle was a particular disappointment. So it's a relief to report that this set of five mature Haydn symphonies, recorded between 2010 and 2011, is a consistent joy. These performances are sharp, affectionate and entertaining. You get shedloads of dry wit. As well as a very vivid sense of Haydn's profundity. Late Mozart symphonies can leave one overawed and feeling humbled. Haydn's music instead conveys a sense of what it's like to be human. Phrases are irregular. Ideas fizzle out. Tempers flare. Jokes get shared. The unpredictability is part of the pleasure. What makes these discs more recommendable is the grandeur of the orchestral sound. The bigger climaxes have sensational impact, though Davis's strings remain brilliantly agile. The Oxford Symphony's Presto is a marvel here – the effervescent main theme surely a model for Prokofiev's Classical Symphony, racing off over a deceptively tricky low horn ostinato. Symphony no 93's Largo cantabile is another highlight, featuring sublime quartet playing. Just in case you think things are getting a little too serious, there's a deliberately disconcerting bassoon blast in the closing bars.

Strange things happen in these pieces. The last movement of no 98 abruptly changes tack in the closing minutes, the texture abruptly thinning to give space for a jaunty continuo solo. Haydn's slow introductions tend to be dark and weighty, making the irrepressible music which invariably follows that much more surprising. There's so much to admire. The Barbican's dryish acoustic really works in Haydn's favour – timpani are nicely in tune and the LSO solo winds excel. A delectable pair of CDs.

Thomas Larcher's ongoing relationship with the piano is traced on this engaging disc. As a developing composer, he associated the piano's sound “with a sense of something worn out, obsolete, at a dead-end...” Wanting to turn the piano into “a different instrument”, he followed Cage's example and prepared the keyboard with rubber wedges and gaffer tape. Larcher's two-movement Smart Dust opens this enjoyable collection. There are moments when you think you're listening to a virtuoso percussion ensemble rather than a pianist, but the music never descends into flashiness. The second section, marked plainly Very fast, is thrilling – intellectually satisfying, amusing and very exciting. After Smart Dust, Larcher returned to the 'conventional' piano, though his 2009 suite What Becomes, written for Leif Ove Ansdnes, does ask for spooky glissandi on the instrument's strings. It's another fiendishly difficult, expressive work, paying homage to Rachmaninov and Mussorgsky while remaining boldly contemporary.

Some of Larcher's twelve Poems make use of ideas sketched while younger; the result is a set of enchanting, quirkily-titled miniatures. Rather like listening to a talented child pianist doodling in the next room. Sad yellow whale is sweet, soft and melancholy, while the rhythmic punch of Frida falls asleep suggests that she's not going to snooze for long. Words can't adequately convey the potency and magic of these little pieces, Larcher's fresh use of tonality avoiding vacuous pastiche. And each one, however slight, is phenomenally played by Tamara Stevanovic, providing beefy thunder as well as calm understatement. There's also a highly accessible song cycle written for tenor Mark Padmore, setting a sequence of oblique contemporary poems by Hans Aschenwald and Alois Hotschnig. Padmore's high register is a thing to marvel at – sample the close of the ninth song. He's beautifully accompanied here by Larcher.

Add comment