An all-Russian prom with two masterpieces centre stage and a remarkably compelling young violin artist brought in a packed house last night. Esa-Pekka Salonen and Lisa Batiashvili have already recorded Shostakovich’s First Violin Concerto, and the bond between them was evident in a delicate yet deeply searching performance of this melancholy, epic work with Salonen's orchestra, the Philharmonia.

The concerto retains its human story indelibly: written for David Oistrakh in 1948, it was not permitted a premiere for seven years, as Shostakovich battled with Stalin's sudden volte-face against him and his music.

Like Oistrakh, Batiashvili intuits the power of the sweet, small voice to stand up in the face of massed ranks, and with her 1709 Stradivarius she spun out long yearning songs over the darkness of the orchestra's basses and horns, touching on unknown images and shuttered parts of the soul. Salonen reined in the Philharmonia’s volume to let her serenely mellifluous sound float those cantilenas high, ideally audible as it threaded through the Albert Hall resonance. If occasionally I felt he removed some of the tension with his careful volume control, Batiashvili decisively re-injected it in her taut playing of the great Cadenza, and she has every bit of the technique required for the lethal difficulties of the last movement.

Like Oistrakh, Batiashvili intuits the power of the sweet, small voice to stand up in the face of massed ranks, and with her 1709 Stradivarius she spun out long yearning songs over the darkness of the orchestra's basses and horns, touching on unknown images and shuttered parts of the soul. Salonen reined in the Philharmonia’s volume to let her serenely mellifluous sound float those cantilenas high, ideally audible as it threaded through the Albert Hall resonance. If occasionally I felt he removed some of the tension with his careful volume control, Batiashvili decisively re-injected it in her taut playing of the great Cadenza, and she has every bit of the technique required for the lethal difficulties of the last movement.

This work was the soul of the concert, sandwiched between two vibrantly colourful, vernacular ballets: Shostakovich’s 1930 suite The Age of Gold and Stravinsky’s 1911 Petrushka, in his later 1947 orchestration, and it was charming that Batiashvili picked up the dance motif for her encore, a lyrical little Shostakovich piano waltz in a sugary orchestration as beguilingly sweet as a cake. What a magician she is, and only 31 yet. (Batiashvili pictured left, photo Anja Frers/DG)

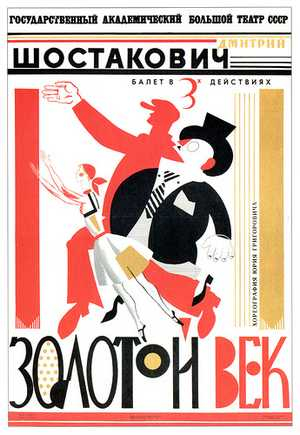

The Age of Gold is surely unique in provenance, being created to a libretto that won an all-Soviet competition for best ballet story. It is a clumping parable about heroic Soviet footballers beating decadent Western cheats when on tour, and fending off hellish capitalist temptations (the Bolshoi Theatre programme shown right).

The Age of Gold is surely unique in provenance, being created to a libretto that won an all-Soviet competition for best ballet story. It is a clumping parable about heroic Soviet footballers beating decadent Western cheats when on tour, and fending off hellish capitalist temptations (the Bolshoi Theatre programme shown right).

Tea dances, witty games and earthy peasant rounds play into Salonen’s crisp, apple-cheeked conducting. His cleanness made Petrushka the glory of the night, every shade, personality, fabric, trim and animal costume of the Shrovetide fair brought into glittering light by the Philharmonia's infectious colourists. Superb trumpet and flute soloists, a compelling pair of bassoonists, exact drums, the tireless pianist, hokey-cokeying double bassists pounding their fingerboards with their hands, these were vividly dynamic musical characters.

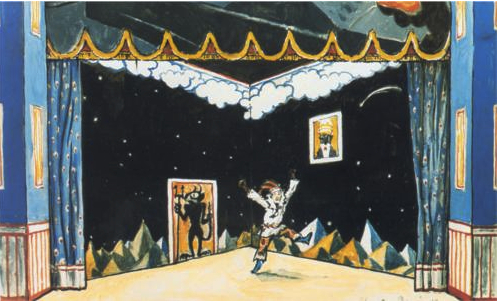

As with Swan Lake the other night, Petrushka is a score which needs no synopsis for you to see its pictures. It had to be, of course, since Stravinsky was told by Diaghilev that it would be designed by that eye-blasting colourist Alexandre Benois (Benois's design sketch, pictured left). But the music’s bravura knows no bounds, from the hectic crowd incidents to the inside track of the puppet Petrushka’s dislocated, desperate world, immortally represented on lurching trumpets. It’s not emotive music, it’s dazzlingly descriptive, and Salonen proved an ideal descriptor.

As with Swan Lake the other night, Petrushka is a score which needs no synopsis for you to see its pictures. It had to be, of course, since Stravinsky was told by Diaghilev that it would be designed by that eye-blasting colourist Alexandre Benois (Benois's design sketch, pictured left). But the music’s bravura knows no bounds, from the hectic crowd incidents to the inside track of the puppet Petrushka’s dislocated, desperate world, immortally represented on lurching trumpets. It’s not emotive music, it’s dazzlingly descriptive, and Salonen proved an ideal descriptor.

The Prom could have ended there, very satisfyingly, and the jolt back to Tchaikovsky’s lushly romantic Francesca di Rimini was, for my taste, a mis-step from the 20th century where we had been so entrancingly ensconced. Not least because in the Albert Hall one is intensely aware of different groups of instruments, dependent on where you sit. It's hard to hear the orchestra as a single organic source of sound, and Francesca di Rimini needs those surging horns and drums to be close-woven with the violins in one big purple whole. From where I sat on the right, the brass and percussion were disconnected entirely from the violins, which almost certainly contributed to my feeling that the performance lacked love’s sickly longing. It told of pain, but it did not express the pain. Exciting, dynamic, yes, but not smelling enough of its own century, its own perilous mortality.

- Listen again to this Prom for the next seven days on the BBC iPlayer

- Salonen and the Philharmonia play at the Edinburgh International Festival next week: Scriabin, Ravel and Stravinsky at the Usher Hall on Tuesday, 23 August

- theartsdesk's pick of the Proms

- theartsdesk's BBC Proms 2011 complete listings

- Find Batiashvili and Salonen's new DG recording of the Shostakovich First Violin Concerto on Amazon

Add comment