"You have to start somewhere," Debussy is reported to have said at the 1910 premiere of The Firebird. Which, at least, is a very good "somewhere" for Stravinsky, shot through with flashes of the personality to come. The Symphony in E flat of two years earlier, however, is little more than a theme park of all the ingredients amassed in Russian music since Glinka forged its identity less than a century earlier. It's fun to have on CD - and to play the opening in a "guess the composer" quiz (the reasonable answer would be Glazunov). To work in concert, it needs companions with more than the passing flashes of inspiration we heard in Vladimir Jurowski's Stravinsky series opener last night, however well connected the music by the four great composers.

What's worth salvaging of the symphony, revised (curiously enough) in 1913, the year of The Rite of Spring? (Stravinsky, incidentally, never referred to it as "No 1," as the LPO publications department seems to think, which would grace it with a higher status than it deserves, though he did record it as conductor in later life. Update: See Richard Bratby's comment below). The first movement is plump and placid, though smoothly upholstered by a London Philharmonic Orchestra on fine form, the third a blatant homage to the finale of Tchaikovsky's "Pathétique" Symphony without the depth of feeling behind it, the finale very much third-best to Borodin in festive mode.

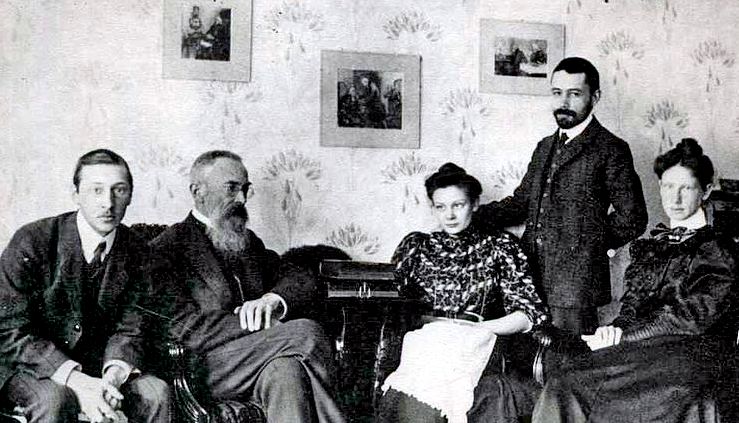

That leaves the effervescent scherzo; there isn't a dull one in the whole history of the Russian symphony, that I know of at any rate, and it's delicious to know that Diaghilev had it played in Ballets Russes intervals; the unlikely Savoyard may have liked its resemblance to the weather chat of Major-General Stanley's daughters in The Pirates of Penzance. At any rate the LPO's wonderful principal flautist Juliette Bausor managed to make real phrasing out of the babble; and she got to sing one of the finest legato melodies of the evening at the beginning of the concert, a welcome chance to hear the rarely-performed Skazka (Fairy Tale) of Stravinsky's mentor Rimsky-Korsakov (pictured above on the left with Stravinsky in 1908).

That leaves the effervescent scherzo; there isn't a dull one in the whole history of the Russian symphony, that I know of at any rate, and it's delicious to know that Diaghilev had it played in Ballets Russes intervals; the unlikely Savoyard may have liked its resemblance to the weather chat of Major-General Stanley's daughters in The Pirates of Penzance. At any rate the LPO's wonderful principal flautist Juliette Bausor managed to make real phrasing out of the babble; and she got to sing one of the finest legato melodies of the evening at the beginning of the concert, a welcome chance to hear the rarely-performed Skazka (Fairy Tale) of Stravinsky's mentor Rimsky-Korsakov (pictured above on the left with Stravinsky in 1908).

Skazka is putatively based on the Prologue to Alexander Pushkin’s first masterpiece, the verse romance Ruslan and Lyudmila, in which a cat held to an ocean-side oak tree by a gold chain sings all the familiar Russian fairy tale components. We can make some of them out – Baba Yaga, for instance, in spiky wind chords indebted to Glinka’s characterisation of the witch Naina in his operatic Ruslan – and the atmosphere is close to Kashchey the Immortal, Korsakov’s one-act opera which gave so much musically to The Firebird (Stravinsky quotes its damsel-in-distress theme in the finale of the E flat Symphony). Bewitchingly scored ideas all, but they don’t amount to much.

Nor do the three lopsided movements of Stravinsky’s Opus Two, Faun and Shepherdess, also based on Pushkin poetry. Debussyan impressionism enters the otherwise Russian fantasy picture here, and it was good to get such a lovely mezzo colour from recently-graduated Angharad Lyddon (pictured right). She holds the stage personably, too; what a grievous omission on the LPO’s part, though, not to give us the Pushkin text and translation either in the programme – hardly a generous celebration of a major festival – or in surtitle form.

Nor do the three lopsided movements of Stravinsky’s Opus Two, Faun and Shepherdess, also based on Pushkin poetry. Debussyan impressionism enters the otherwise Russian fantasy picture here, and it was good to get such a lovely mezzo colour from recently-graduated Angharad Lyddon (pictured right). She holds the stage personably, too; what a grievous omission on the LPO’s part, though, not to give us the Pushkin text and translation either in the programme – hardly a generous celebration of a major festival – or in surtitle form.

Glazunov’s Violin Concerto is oddly proportioned, too, despite its compactness: all introspective lyricism verging on the soporific until it reaches one of the best finales in the concerto repertoire, twinkling variations on a hunting theme. It’s an inspiration in which you want to see the violinist having fun; but Kristóf Baráti (pictured below by Marco Borggreve) deprived us of any pleasure in the visual dimension, eyes down and serious throughout. No denying the deep tone and mostly spot-on intonation, though, and he spun a bewitching line in the Glazunov-orchestrated Meditation from Tchaikovsky’s Souvenir d’un lieu cher which followed.

This was Tchaikovsky’s first idea for the slow movement of his Violin Concerto – the ultimate vivacissimo of which Glazunov definitely rivals – and Glazunov parallels the clarinet embroideries of the much better-known concerto canzona in the reprise of the melancholy melody. Guest principal James Burke gave us more personality than Baráti, joining Bausor to prove that the LPO’s wind principals are every inch the characterful equal of the Philharmonia’s, on show so strikingly in last Thursday’s Dvořák concert, or those of the BBC Symphony Orchestra. Treasure your London orchestas, and do not seem to wish Brexit on their healthy pan-European constitution, as LPO Chief Executive and Artistic Advisor Timothy Walker appeared to do in a gobsmacking Daily Telegraph article last week. There are questions there which he needs to answer; but meanwhile the orchestra is in peerless shape, so thanks partly to Walker as well as mainly to Jurowski for that.

This was Tchaikovsky’s first idea for the slow movement of his Violin Concerto – the ultimate vivacissimo of which Glazunov definitely rivals – and Glazunov parallels the clarinet embroideries of the much better-known concerto canzona in the reprise of the melancholy melody. Guest principal James Burke gave us more personality than Baráti, joining Bausor to prove that the LPO’s wind principals are every inch the characterful equal of the Philharmonia’s, on show so strikingly in last Thursday’s Dvořák concert, or those of the BBC Symphony Orchestra. Treasure your London orchestas, and do not seem to wish Brexit on their healthy pan-European constitution, as LPO Chief Executive and Artistic Advisor Timothy Walker appeared to do in a gobsmacking Daily Telegraph article last week. There are questions there which he needs to answer; but meanwhile the orchestra is in peerless shape, so thanks partly to Walker as well as mainly to Jurowski for that.

Add comment