David Coleman never said, "Juantorena opens his legs and shows his class," any more than Queen Victoria said, "We are not amused." The words belonged to Ron Pickering, but Private Eye got it wrong. The chances are that Coleman, who has died at the age of 87, was not amused. A lot of people were, however. Who knows how much damage that one mis-attribution did, how much it contributed to the image crisis that Coleman put up with for so many years?

Undeservedly or not, it is the lot of the British sports commentator to suffer the barbs and carping of his or her public. Some of them, and Coleman was certainly one, are as much a part of the national picture as the sportsmen whose acts of valour they describe. Private Eye's Colemanballs is the distillation of that. That the sports blooper column should be named after him has never remotely undermined Coleman's position as the undisputed founding father of modern British sports broadcasting, the commentator who moved the hearts other commentators cannot reach.

More or less since the inception of the BBC's regular outside sports broadcasts, Coleman's was the voice that brought the event into the living room. He anchored Grandstand and Sportsnight long before anyone had ever heard of Frank Bough or Desmond Lynam. He was the first commentator whose voice proclaimed that he neither attended a public school nor pretended to have done.

By some accident of anatomy, his tear ducts were apparently located somewhere inside his larynx

His background, both in sport and sports journalism, was in the north-west. A county-standard middle-distance runner, the height of his athletics career was winning the Manchester Mile in 1949. He also turned out a few times for Stockport County reserves. Starting on the Stockport Express, he moved through a succession of local newspapers, and began freelancing on the radio in 1953. His stint as a news assistant on a Birmingham paper held him in good stead during his finest hour when, at the Munich Olympics in 1972, he held the fort magnificently as a reporter after the Israeli athletes were taken hostage in the Olympic village.

In 1959 he arrived at the BBC, where over the years he and Pickering formed one of the great unsung double acts of British television - unsung because although they were indomitably professional they weren't quite without ostentation or foible. Pickering, a registered athletics coach and a vocal anti-drugs campaigner, was the swotty one, all nous and info. If there was anything he didn't know about the Bulgarian hurdler, the Somali marathon runner or the Finnish javelin thrower, it wasn't worth knowing. Coleman, who was not as immersed in the sport to the same depth as Pickering, could never compete on these statistical or technical fronts. His job was to inject the hysterics, to get as excited as a demented despot in full oratorical flight.

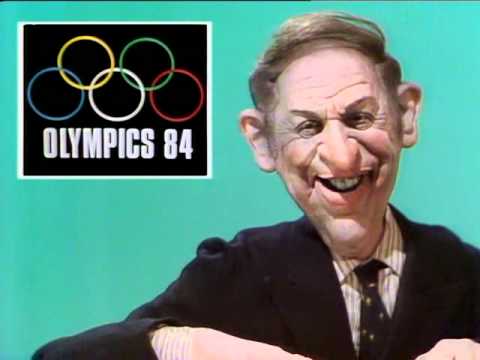

There was never a shortfall in drama when Coleman was at the microphone. Spitting Image caricatured him as a commentator who literally explodes at the merest hint of athletic action. In one sketch he reaches fever pitch as Seb Coe breaks for the line with 600 metres still to go. "And I've gone far far too early!" he screams with about a minute of commentating time to fill. "I'll never be able to keep up this level of excitement!!"

There was never a shortfall in drama when Coleman was at the microphone. Spitting Image caricatured him as a commentator who literally explodes at the merest hint of athletic action. In one sketch he reaches fever pitch as Seb Coe breaks for the line with 600 metres still to go. "And I've gone far far too early!" he screams with about a minute of commentating time to fill. "I'll never be able to keep up this level of excitement!!"

"We do occasionally get over-enthusiastic," he once admitted, "but viewers don't understand sometimes the pressures we work under." His trick was always to sound as if he didn't expect to get anything wrong. He was the BBC's senior football commentator for most of the 1970s, and when the first goal of a game was scored, he had a way of saying "One-nil" that vigorously implied he knew it had been coming all along.

By some accident of anatomy, his tear ducts were apparently located somewhere inside his larynx. He had a voice that sounded as if it is going to start crying any second. Once, famously, he very nearly did cry, when Ann Packer took the 800 metres gold in Tokyo in 1964. (Many years later, and for a very different reason, he nearly did again, when he commentated at an athletics meeting for the first time since Pickering's death.)

It was perhaps because of this that Coleman was never frog-marched off to the minority sports - badminton or bowls, fencing or volleyball - where his sense of drama would have been misplaced. His legal wrangle with the BBC in the mid-1970s, which kept him off the screen for a year, centred on his complaint that he was used too parsimoniously and did not have enough editorial involvement.

It was perhaps because of this that Coleman was never frog-marched off to the minority sports - badminton or bowls, fencing or volleyball - where his sense of drama would have been misplaced. His legal wrangle with the BBC in the mid-1970s, which kept him off the screen for a year, centred on his complaint that he was used too parsimoniously and did not have enough editorial involvement.

That dispute revealed a hard-headed side to the man whose affability is one of the ingredients which make the Coleman-chaired A Question of Sport, with its Pringle pullovers and pub repartee, a cosy long-running success.

In 1990 the nation was informed that he had suffered a heart attack - and no wonder, one might think, given the emotionally exacting nature of his job - but it turned out to be shingles. He reached retirement age in 1991 but carried on working. The Sydney Olympics in 2000 was his 11th and last. He was 74, but for those of us who grew up on his voice, he went far far too early.

Add comment