The news last week that Michael Grandage will step down next year as artistic director of the Donmar Warehouse feels like one of those moments when an era ends. His ability to programme not only the small Donmar but also to bring excellent productions to the West End — notably Jude Law in Hamlet — is exemplified in the current mini-season at the Trafalgar Studios, which opened last night with American playwright Beau Willimon’s new play about the New Orleans floods of 2005.

The concept of the play is simple. Following Hurricane Katrina, two African Americans, Malcolm and EZ, find themselves stranded on a New Orleans rooftop waiting for rescue. Malcolm is a mid-forties Bible-bashing ex-addict and EZ is a twentysomething youth. They are in the city’s Lower Ninth district, their lives have been devastated, their worldly possessions swept away and the body of one of EZ’s childhood friends, the gangster Lowboy, is lying on the roof with them.

Willimon, who was writer in residence at the Donmar a couple of years ago, has set up a situation which focuses tightly on the characters of the two men — and on the tensions between them. For while Malcolm believes in God, and is likely to spout passages from the prophet Ezekiel or tell the story of Noah (and even, in one hilarious bit, the version which explains why the biblical patriarch was black and other distant ancestors of humankind became white), EZ just has faith in money and crime. Slowly, it emerges that the two men are intimately linked and, in one moment of astonishing intensity, Willimon comes up with a quasi-religious image which encapsulates the idea of the blood of life.

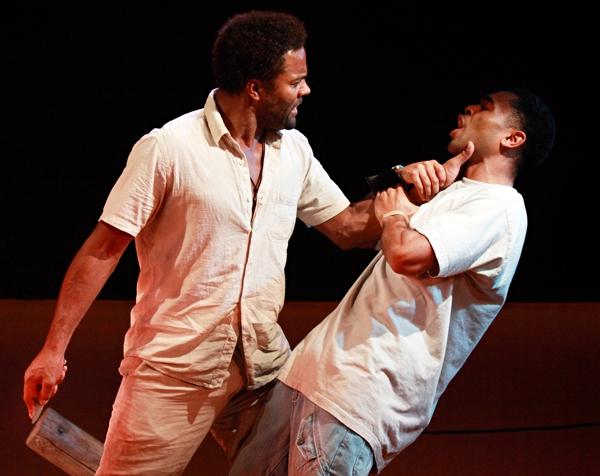

But tense relations on a decayed rooftop can only get you so far, and although Malcolm and EZ pass the time by sparring or by playing 20 questions, there is a real need for another character to appear. After all, even the two tramps in Beckett’s Waiting for Godot have visitors. In answer to this prayer, Lowboy suddenly gatecrashes EZ’s dreams. Don't worry; since the actor playing Lowboy is listed in the programme, this is not a spoiler.

The nature of faith, the poverty of aspiration, the sense of injustice and a burning desire to do the right thing, to commemorate the dead with all due respect - all this is the raw meat of what is, at about 70 minutes, a rather slender play. Yet, brief as it is, it is full of powerful emotions: paternal love, survival instinct, and a need to be part — in some way — of an American Dream that has rarely seemed more elusive. As the two men bake under the merciless sun, you can’t help thinking of the victims of other natural disasters, past and present.

The first play in Donmar Trafalgar, a new initiative giving young directors the chance to stage their own production, Lower Ninth is directed with great intensity by Charlotte Westenra. As Malcolm, Ray Fearon gives a very strong performance, suggesting both the fanaticism of the born-again believer and the tenderness of the former bad boy who has now seen the light. By contrast, Anthony Welsh’s EZ bursts with the energy, arrogance and incoherence of youth, although he can never hope to match the physique of Richie Campbell’s Lowboy, who is a very impressive presence.

Ben Stones’ rooftop set takes up most of the playing space while Abram Wilson’s music creates an atmosphere of dread. This is a tough, humorous, and mildly redemptive piece of playwriting from a talent we will doubtless hear more from.

Add comment