The great Caryl Churchill careers down a blind alley in Here We Go, and the results aren't pretty, especially within the cavernous confines of the National Theatre's Lyttelton – this writer's second play this year at that address. A 45-minute triptych about death that gets worse as it goes on, the play put me in mind of the American critic Walter Kerr's famous remark about Neil Simon not having an idea for a play but writing one anyway. On this occasion, it would occur that Churchill had an idea or two and then forgot to write the accompanying play.

That, in turn, comes as something of a shock from easily the most adventuresome living British dramatist: a talent, now age 77, for whom form and content are so jointly audacious that her premieres spark a sense of anticipatory excitement that is without peer. (Luckily, there's a new one, Escaped Alone, arriving at the Royal Court early in 2016, by which point Here We Go will have long since gone.)

And while intimations of mortality remain among the most resonant of all theatrical themes, all Here We Go really does is make one realise how much better – that's to say, more trenchantly, poetically, allusively – Beckett, Sartre, and Pinter, to name but three, have effected variations on the landscape Churchill puts before us here. Most disturbing of all is the absence of any proper excitement in the language, and this from a dramatist who can make a single word (the final "frightening" in Top Girls, for instance) land a knockout blow.

And while intimations of mortality remain among the most resonant of all theatrical themes, all Here We Go really does is make one realise how much better – that's to say, more trenchantly, poetically, allusively – Beckett, Sartre, and Pinter, to name but three, have effected variations on the landscape Churchill puts before us here. Most disturbing of all is the absence of any proper excitement in the language, and this from a dramatist who can make a single word (the final "frightening" in Top Girls, for instance) land a knockout blow.

Some will lump this offering with the week's concurrent National Theatre debut of the new Wallace Shawn play, Evening at The Talk House – Shawn being a maverick thinker (and leftist) cut from much the same cloth. In fact, the two plays couldn't be more qualitatively at odds, and my appreciation for the keen layering of Talk House has only been deepened by the bald-faced banality on view here. The shorter play's opener posits an assemblage gathered for a funeral who speak in Churchill-lite half-sentences and turn towards us on cue to relate the time and manner of their respective deaths, one of the reports paying direct homage, or so one assumes, to the vaunted American theatre director Alan Schneider, who was killed in a motorcycle accident in London in 1984.

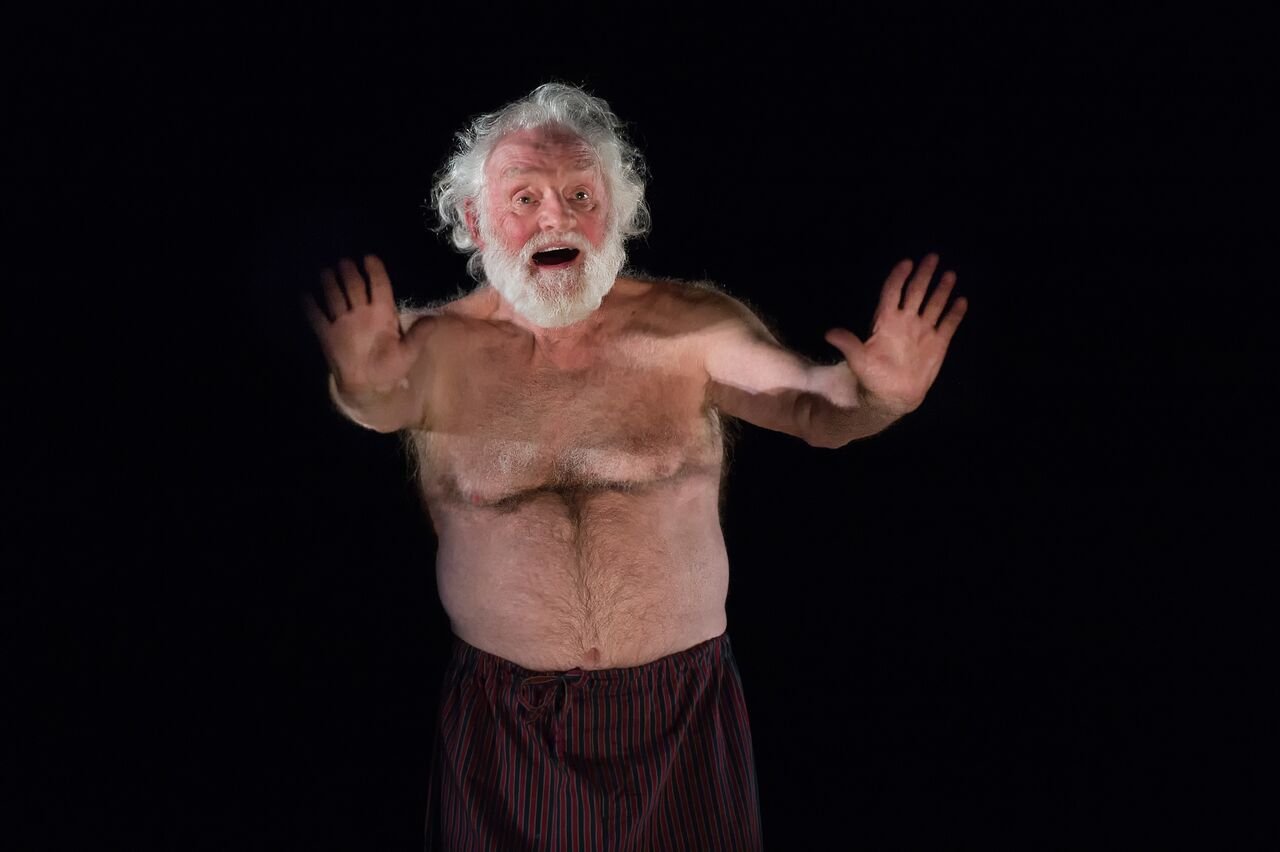

So far so clever, albeit in a rather forced way, when Vicki Mortimer's deliberately faceless set suddenly shifts and we find ourselves staring down a bare-chested Patrick Godfrey (pictured above), who speechifies about "falling down the tunnel of light" and ponders not very amusingly whether the pearly gates might contain actual pearls. The monologue is staged by the director Dominic Cooke as if it had an incantatory power that it doesn't begin to possess, and one can't help feeling that Shakespeare made much the same points in a far more compressed manner in his "Seven ages of man" speech from As You Like It, yet another concurrent National entry.

The tireless Godfrey reappears in the final, and (you'll forgive the adjective) deadliest, section: a wordless study in repetition that carries the textual subtitle "getting there" and finds Godfrey being dressed and undressed repeatedly while assisted by a carer (Hazel Holder) as the lights fade to black. I doubt I am alone in having of late assisted in much the same situation in my own life, and I can attest that such rituals are infinitely more dramatic than Churchill begins to let on. Then again, if her aim was to drain the theatre of all palpable life, she has done the trick, and Godfrey and Holder retain admirable focus even as a dumbstruck audience fades to grey.

Add comment