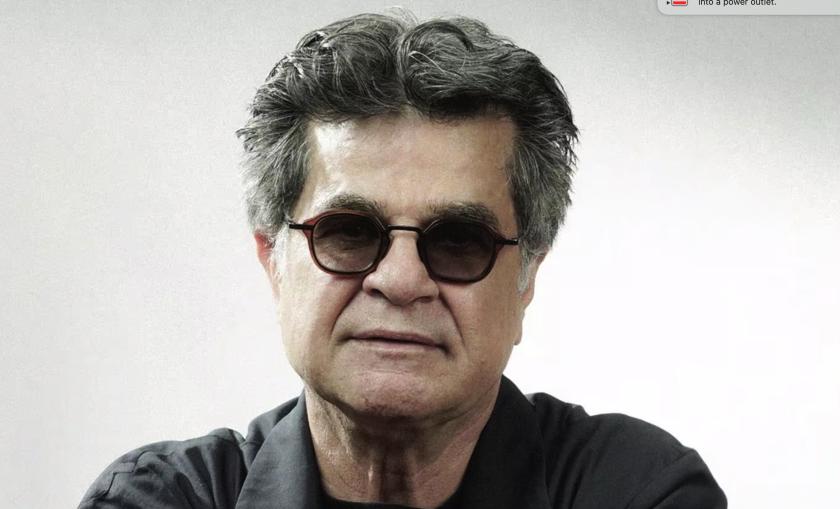

Even more than his new film, Jafar Panahi was a sensation at Cannes this year. For the first time in 15 years, the Iranian director was able to present a work in person at the festival. Two arrests by the Iranian government, which had followed his 2010s 20-year house arrest, had made him a prisoner of the state.

Nevertheless, Panahi has continued to film without official permission. He managed to shoot five films this way, including Taxi Tehran which won the Golden Bear at the 2015 Berlinale. Shortly after his release in February 2023, he proceeded to make It Was Just an Accident, which won the Palme d'Or in May.

It's a film full of anger and unprocessed pain as you might expect from an unyielding director who recalled his own time and that of others in jail while writing the script. The bitter farce of a mechanic who thinks he’s captured the man who once tortured him is more than just an outrageous tale of rage and revenge. Instead, Panahi turns the story into an unusual road movie that questions humanity at its core, as well as forgiveness.

For Panahi himself there is no reason to feel relieved. “How can I be happy and free here,” he said shortly after the Cannes premiere, “when directors and even the greatest actors in Iran cannot work there?” Still, the experience of seeing his film with an audience again after so many years excited him. “It's almost an otherworldly experience. And it adds a whole new dimension, because you can always work out your strengths and weaknesses as a director according to how the audience reacts to the film.” This interview, which took place at the festival, obviously does not reflect that the Iranian authorities arrested Panahi in absentia again last week while he was promoting It Was Just an Accident in the US.

PAMELA JAHN: How do you look back at your time in jail?

JAFAR PANAHI: Compared to what other prisoners go through, I went to take a rest.

Which of your own experiences did you use in the script?

The film does not reflect my own situation. The idea was to focus on the people who spent five, ten or more years in prison. When I was there, I had long conversations with them. We spoke about their experiences and the events that they had witnessed of other inmates. We spoke about half a century of imprisonment in Iran.

It Was Just an Accident is an angry film, but there is also an underlaying sense of gallows humour at times.

Irony plays a great part in our culture. If you spend a single hour in an Iranian market, you start to notice how humorously people interact with you. You might even see a major disaster strike and 10 minutes later people are already making jokes about it. It's really not that strange.

Do you believe that people who torture other human beings can live a happy life?

You made me think of the question Hannah Arendt asked herself when she went to Israel for the Adolf Eichmann trial. I'm paraphrasing but she says something like, "We're all imagining this monster. But the man they brought into that glass cage, we found it hard to believe that such a normal looking man could have done such evil." Apparently, that's how it is. People might not be as normal as they appear from the outside. But of course, I also put some clues in my film.

In what way?

It's clear that the [captive’s] family [seen at the beginning of the film] is highly ideological. For instance, the father won't allow for the music volume to be turned up too high. And even just their outward appearance signifies to some extent that this is a family that is very close to the regime. And when the accident takes place, the little girl says to her father, "You killed him, the dog." And the mother replies, "No, it wasn't your father's doing. It was God's will." That way, she is setting out an ideological matter. But immediately, with a very simple sentence, the girl questions the absolute fundament of their ideology when she asks, "What do you mean? What God? It was you who were not careful." These are all references, little hints, to get a different perspective on the story that unravels in the film.

You have said that this film is artistically a new beginning for you. What's the path you're following now?

When I wasn't allowed to work, I made more personal films. I was so shocked by the sentence I got back in 2010 that I saw myself really as the pillar for every story and that I should be at the centre of each one of my projects. I thought if I'm going to make a film about a taxi driver, well, I've got a director here who can't work, so he's going to become a taxi driver. And because he's very loyal to his previous job, he's planted cameras everywhere in the car. He's doing both jobs at the same time. But since all my sentences were lifted, what happened technically is that I keep making films the same way. It's only that, psychologically, I've removed myself from the frame.

Your films and those of your colleague Mohammad Rasoulof expose the brutality and repression of the regime. Could you ever see yourselves making a genre film instead?

Why not? It really depends on the idea behind it and what the story needs. But what I do know is that whatever genre I work in, it will always be very close to reality. I have always seen myself as a social filmmaker. I make humanistic films about people and their everyday lives in Iran.

How has not being able to work freely changed you as an artist?

I feel I've changed a great deal after going to prison. So much so that I keep telling myself, I wish I'd been there sooner, because I discovered many things that I would maybe have not seen otherwise, and it got me close to people who I'd never met before. And then, of course, serving time in prison changes you in your personal life, in your personal behaviours. For instance, if you decide to help another prisoner, it's not performative. You really know it profoundly is a duty you have. At least that's how I see it.

Have recent developments in the country allowed you to be more direct in your films?

The circumstances in Iran have not changed that much. We don't live in a freer society. What's happened is that the government is in no position to return to its previous status quo, because people resist it. Every day the authorities impose new punishments, they keep making things tougher, but people no longer obey. It's not that life is less dangerous, but the government can't control the population anymore as they did before.

How did filmmaking and storytelling save you in the last 15 years?

It's the only job I know. I can't do anything else. If I hadn't made films, I'm sure things would have been quite hard. In order not to experience greater hardship, I found solutions that enabled me to do what I love. By doing so, I managed also to signal that we must absolutely keep working. Before 2010, I remember film students coming to me complaining about how difficult it is to make a film. But after watching, This Is Not a Film [2011] or Taxi Tehran, none of them ever complained again. Instead, they found new ways to pursue filmmaking. There're very different ways of resisting. We all find different solutions according to our capabilities.

Is it possible to think about forgiveness in Iran these days?

Probably not, but we can hope that things will no longer be this way in the future. Hope that nobody will force their ideas upon others. Hope that everyone gets to know themselves and becomes a better version of themselves, both people in the government and those who have nothing to do with it. Hope that they'll find a way to live all together without violence.

What do you expect when you're going back?

I have no specific expectation. All I know is that I'm going back, and we'll see what happens. It's really not as bad as it seems. It might look bad from the outside. But when you're there and you compare your problems with the situation of others, you realise how small they are. To give you a very simple example, there's so many women who walk on the street without a head scarf. When they are arrested and it goes particularly badly, they get taken away somewhere. But then, the day after, they do the same thing. But because these women are not well known, nobody pays particular attention. That's real bravery.

Add comment